Guest post by Hugo Campos; introductory note from Society for Participatory Medicine president Nick Dawson

Guest post by Hugo Campos; introductory note from Society for Participatory Medicine president Nick Dawson

Every movement evolves. And as a grassroots social justice movement, the Participatory Medicine Movement is also growing, changing and evolving. Something I’ve learned about myself is how uncomfortable I get when I’m on the edge of learning or gaining understanding. For the past few months, I’ve personally been uncomfortable with some of our terms, definitions and approaches to participatory medicine. To be clear, I don’t know what the future of the Movement is — and would suggest none of us alone has that complete vision.

SPM started in 2009 by redefining the patient’s role to emphasize autonomy. Like any project, we’ve had scope creep; talking about cooperation, ethics, and the now over-covered conversations about patient satisfaction and costs of care. This is not enough. Autonomy and emancipation are totally different issues from “satisfaction” and what things cost. Our goal ought not to be to make ourselves look like everyone else – our goal ought to be to establish what’s missing, what the problem is, and to fix it.

To that end, the essay below from SPM member Hugo Campos makes me uncomfortable in a way I love. I cannot stop thinking about autonomy. I cannot unknow this idea now that Hugo has put it in front of us.

To current SPM members, friends and like-minded thinkers, I invite you to read Hugo’s essay below. Join me in starting a conversation in the comments about how this idea strikes you. Let’s discuss, debate and grow the Movement together.

cheers

-N

_______

Hugo Campos

12/3/2014

“What does participatory medicine mean?” The question, posed on the listserv of the Society for Participatory Medicine (SPM), doesn’t have an easy answer. The SPM currently defines participatory medicine as “a model of cooperative health care that seeks to achieve active involvement by patients, professionals, caregivers, and others across the continuum of care on all issues related to an individual’s health. Participatory medicine is an ethical approach to care that also holds promise to improve outcomes, reduce medical errors, increase patient satisfaction and improve the cost of care.”

The above explains participatory medicine as a model of care which seeks stakeholder collaboration on issues related to an individual’s health (presumably with regard to medical treatment). It also promises to improve outcomes, increase patient satisfaction, reduce medical errors and the overall cost of care. It is a broad and slightly obscure definition with very lofty goals. According to this, participatory medicine promises what is already expected of our current system: cooperation, stakeholder involvement, improved health outcomes.

But, an older definition put forth by the SPM, hinted at what is really at stake here: autonomy.

It described participatory medicine as: a movement in which networked patients shift from being mere passengers to responsible drivers of their health, and in which providers encourage and value them as full partners.

By this definition, the transformation of patients from mere passengers to responsible drivers of their health signaled a shift from patients’ traditionally passive role to a more active, self-governing one. It implied a high degree of autonomy and self-determination and resonated with me the moment I heard it in 2010. It seems, however, that in the course of the past few years we may have gotten lost.

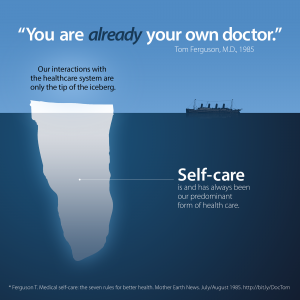

Thirty years ago, Tom Ferguson, M.D., wrote “The seven rules for better health” (bit.ly/DocTom, Mother Earth News, July/August 1985). Dr. Ferguson’s “First Law” pointed out that patients provide their own illness care between 80 and 98% of the time. “You are already your own doctor,” wrote Dr. Ferguson.

As a person living with a genetic heart condition which can lead to sudden cardiac death and congestive heart failure, I can certainly relate to the spirit of autonomy recognized by Dr. Ferguson. When it comes to my health and health care, I, too, believe a high degree of autonomy is paramount. In the past, the system proved itself incompatible with my needs, or completely unavailable during the 13 months when I was forced to go uninsured due a “pre-existing” condition. This shows how extremely challenging it can be for a true partnership to exist.

Thus, a good dose of self-reliance and independence on the part of the patient is absolutely necessary when managing a chronic condition, as it would be unrealistic to expect 24/7 clinician support on the hundreds of health-impacting decisions I make every day. Surely, no one is more available than the patient herself, her family, her friends and her online network of peer patients.

There is another critical limitation to the kind of partnership that doctors and patients can develop. Much as with the the fable of the chicken and the pig, there’s a fundamental difference between the doctor’s involvement and the patient’s commitment in their care. In business, true partners share both risks and benefits. But this is not possible in healthcare, where the patient alone lives (or dies) with the consequences of medical decisions. That’s where the participatory medicine notion of doctors and patients as equal partners falls apart. Therefore, the patient alone must develop a sense of personal responsibility and learn to practice the inalienable nature of her authority over herself, if she so desires.

Consider Dr. Ferguson’s view of self-care as the predominant form of health care. This is where patients are free to fully exercise their self-determination, deciding how to eat, exercise, care for their emotional well-being, or whether to smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol and engage in dangerous or harmful behaviors. This is potentially disastrous from a public health perspective. Yet, we are tolerant of this model in part because we believe that, like ourselves, most people do not intend to make their lives worse by their own choosing.

The U.S. Census Bureau tells us that the average number of medical provider visits per year is close to 4. That’s only 4 interactions with health care per year. If patients already spend most of their time caring for themselves without a doctor’s supervision, it would seem reasonable to empower them further and trust their knowledge of themselves. To quote Dr. Ferguson’s “Second Law”, “some of the most promising opportunities for improving our health care system involve finding ways to make health tools, information, skills, and support available through lay channels”. Imagine a world where medical journals are open to public access and not locked behind a paywall.

Finally, we must think of patient autonomy as not simply a status or principle of medical ethics. Autonomy is a skill that must be encouraged, developed and maintained. Patients must engage in the practice of autonomy as physicians engage in the practice of medicine.

Alas, patient autonomy is an ideal that can never be perfectly achieved in clinical care. It often ends where it may conflict with a physician’s duty to beneficence. Even the most empowered of epatients cannot always be completely autonomous. We must accept that. There are, however, autonomous moments in care where patients can exercise self-determination. Those moments should be supported and encouraged.

Autonomy is true empowerment. It promotes patient responsibility and holds the promise to lead us to more engagement and better health. We must move beyond participatory medicine and focus on educating, enabling and equipping patients with the tools necessary to master autonomy and the art of self-care.

We all ARE our own doctors, but medical care is set up to deliver MEDICAL care, not health care, so we wind up on a conveyor belt if we’re not careful. Which is exactly the point that I think Hugo makes: each of us must take the responsibility of being our own primary care providers.

SPM’s role here can (should?) be as a resource repository and community forum for all who want to make autonomy available and practical for everyone. Literacy tools, technology that helps us track our own health status, community collaboration that gives people with medical conditions access to peer-to-peer and professional input.

Your thoughts?

Casey, I agree. I think the SPM should focus on advancing patient autonomy and ending paternalism.

Agree *completely* – and some of us have already started crafting action plans. Particularly Peter Elias (his comment is below, and a must-read). Let’s DO THIS.

Hugo – Terrific, thought-provoking piece. I hadn’t read Dr. Ferguson’s 1st Law until now but it aligns with my thinking. In contrast today’s “state of the art” tools for individuals are so-called “patient portals” that give an abridged view of what happened at the provider. When we have an easy to adopt/use Collaborative Health Record (CHR) that is focused on the “other” 99+% of an individual’s life when they aren’t with a provider, we’ll be helping with the autonomy goal you so articulately describe. The CHR should encompass the full gamut of all medical encounters but more importantly capture the other 99% of the individual’s life as represented by everything from family medical history to personal preferences (people have different levels of medical intervention they desire), social/geo history, biometric data, genomic information and more, this will create a magnet for the healthcare system.

That magnetism will be much stronger in fee-for-value based healthcare models. The difference in the care I see in fee-for-value is far superior to what I see in the typical do-more, bill-more model of care which is why I tried mightily to get my elderly parents to shift to a model that supports the kind of autonomy you describe. It wasn’t easy as they were accepting of the status quo they had but happily, I was able to get them to switch and it’s already reaping dividends.

I look forward to your follow-up thoughts. Great job articulating this!

Dave, I agree that a Collaborative Health Record is an important step toward autonomy. Today, my health data is scattered everywhere. I must actively pursue it, manually collect it and meticulously file it in a cloud-based storage I manage. Any provider who will help me with this task will get my loyalty and commitment to remain engaged — if my autonomy is preserved.

Nick, many thanks for sharing Hugo’s article.

It sounds like SPM will potentially be re-named SAH (for the Society for Autonomous Health). Having been part of the “original” e-health movements when Mozilla came on the scene in the early 1990’s and having taken hiatus for two decades, it appears we have another key opportunity window to seize today.

I’m not sure this is an either/or proposition. Of course we want patients to be independent and choose their own care — inside and outside of hospitals. Participatory medicine supports a patient’s entire autonomy and self-care and always has.

Participatory medicine may — at the moment — *focus* on the doctor/patient relationship in many of its current forms, but that doesn’t mean it excludes or discriminates against other forms of health care — including self-care. (I’m not sure why some folks feel this is the case, but it’s not anything the movement has ever stood for.)

Participatory medicine is, quite simply, supporting people who are willing & able to engage in their own care, and care choices, at any point in their life, in any realm of their life, for any component of care of their health and well-being. In any stage of autonomy or not. It may include a professional, it may not. It may include others, it may not.

The key is the empowered, independent patient who takes charge of their own health and care. In whatever form that may be.

Thanks for weighing in here, Dr. John. Of course this is not an “either-or” discussion – as you correctly remind us: “Participatory medicine supports a patient’s entire autonomy and self-care and always has.”

I’ve been cheering on Hugo’s pro-active efforts to access his own ICD data, yet I also recognize that Hugo is in fact an outlier – an intelligent, educated, tech-savvy, highly-motivated activist who is spectacularly different than your average freshly-diagnosed heart patient.

These are the patients I’m actually worried about: they’re not only non-autonomous, they’re barely participatory in far too many cases.

I often feel dismayed about this reality. I ask my women’s heart health presentation audiences (in very unscientific survey examples over the past seven years speaking to thousands of women) this basic question: “How many of you know what your blood pressure numbers are?” It is routine to see barely one-third of the hands in the room go up. When I then ask how many don’t know their BP numbers, but their doctor has assured them ‘don’t worry, be happy?’ – the rest of the hands shoot up.

Or consider the beautifully-dressed older woman in one of my audiences who asked during my Q&A session: “Carolyn, my doctor says I have a heart rhythm problem. What does that mean?”

To me, she represents the overwhelmed, disengaged, uninformed, definitely non-participatory and often very ill patients who have yet to be introduced to even the most rudimentary concepts of participatory medicine.

So, as Hugo wisely reminds us here, there seems to be a natural life cycle for the insiders of a given movement. Yet for the vast majority of patients living with chronic illness (particularly those living with multi-morbidities and thus what Mayo’s Dr. Victor Montori calls “the burden of treatment”) what’s being discussed here is insider musings and hegemonic assumptions that we are somehow all the same in our drive to be drivers of our own care.

We are not. We have an interminably long road to go before we’re even close.

regards,

C.

Carolyn, during the Suffraget movement, most women were not interested in engaging in their right to vote and the suffragets were considered outliers. Voting is now a democratic right but it comes with the responsibility to stay informed and learn about the system. Should not out own health be associated with similar rights and responsibilities?

Carolyn, thank you for the kind words. But we must not perpetuate the paternalistic behavior we find so distasteful when it interferes with our own sense of autonomy.

It is not our job to make decisions for other rational adults. It is paternalism to justify a rule, a policy or an action on the grounds that those affected by that rule would be better off as a result, when actually, the person in question would prefer not to be treated that way.

If patients are disengaged, uninformed and overwhelmed, it is likely due to our inability to educate and encourage them to participate, and equip them with tools that foster autonomy. They are a product of a paternalistic system that does not encourage autonomy. We must recognize that.

Thank you to both Sarah and Hugo for your prompt responses to my comment here. Please don’t get me wrong – my fondest hope is indeed that one day very very soon I will no longer have any people in my audiences who are so blithely disconnected from/uninterested in their own health. I’m trying to do my bit, little by little, to encourage these audience members (with gentle bonks on the head, sometimes!) to start taking “responsibility” for their own health.

Meanwhile it’s important to acknowledge the actual lived experiences of the vast majority of patients who are just now only starting out on the road to participatory medicine. It’s patently unwise to make assumptions that all patients can somehow fast-forward through participation, straight to autonomy.

Reminds me of a recent Canadian study reporting that only 5% of physicians use Twitter for professional purposes. The study was met by absolute incredulity, disagreement, and outright scoffing by the active Twitterverse throughout Canada, those described by Pat Rich of the Canadian Medical Association Journal as “those of us who live and breathe social media in health care.” Again, we’re assuming that because we’re very involved, everybody else must be, too.

Not even close to being true.

John, I am not convinced that the current SPM definition of participatory medicine supports autonomy. It used to, but no more. We have allowed for it to be diluted in our attempt to get every stakeholder on board. We have compromised autonomy for partnership. That’s unfortunate, in my view. I can’t always rely on a partnership with my provider, but I can and have successfully relied in my autonomy over and over again.

Hugo, right on the SPM homepage it repeats the older definition of PM: “The Society for Participatory Medicine is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization devoted to promoting the concept of participatory medicine, a movement in which networked patients shift from being mere passengers to responsible drivers of their health, and in which providers encourage and value them as full partners.”

While I agree the two definitions are potentially confusing, SPM has never said we don’t stand for all of what PM may be defined as — yesterday, today and tomorrow. In a new field such as PM, things like the exact definition are in flux as we all try and navigate this new world.

I would also argue there’s nothing in the other definition of “cooperative health care” that means a patient’s autonomy isn’t fully supported. “Cooperate” doesn’t mean “bow down before my decision.” It means, hey, if you’re doing X,Y and Z on your own and you go talk to your doc, maybe you should mention X, Y and Z to them. Why? So they don’t prescribe you a treatment that may be in conflict (or contra-indicated) with those X, Y and Z things you’re doing.

SPM is and always has been about supporting a patient’s decisions in their own health care, regardless of where that happens. I’ve never seen anything SPM has done (actions speak louder than words) that would contradict that.

Thanks, Hugo. Autonomy is essential to humanity. Without it, we become The Borg.

In an era of information technology abundance by almost any measure, our health care system is almost completely opaque with respect to quality, cost, and collaboration. And, in the most important way it’s getting worse, not better.

Medicine, here defined as the combination of patient specific information with generalized knowledge, is shifting towards secrecy in the form of secret software that is no longer peer-reviewable. Transparency is shifting in the wrong direction. Our physicians, once autonomous to practice, innovate, and teach under a professional license have now become the agents of the institution.

“Participatory” medicine obscures the loss of autonomy by physicians as well as patients. What we need is open access to both our private information AND to the generalized knowledge we call medicine. Information and knowledge are non-rivalrous goods. Our current trend toward privatized patient information silos and transmutation of medical knowledge into intellectual property apps is now hiding behind the participatory medicine facade.

Wonderful posts and fantastic discussion!

As a person living with Parkinson’s disease for over 20 years (had my first symptoms around 1984, age 13-ish, but not correctly diagnosed until 20013), and doing unusually well, I completely agree with the sentiments expressed. I have learnt so much more from my fellow patients in different diseases, than I have learnt from healthcare. And I spend very little time with my neurologist, 1 hour per year, while I spend 8,765 hours in selfcare (see http://www.riggare.se/1-vs-8765/).

In my opinion, it’s not a case of waiting for healthcare to change to accommodate our needs. We don’t have the time to wait. And autonomy doesn’t mean “do not need healthcare”, to me it means “knowledgeable and able to make decisions about my own health with the support of healthcare”. And you know what? If healthcare starts acknowledging our knowledge, they will learn a lot! :)

I am somewhat thrilled when we get past the “Doctor knows best” part of our erstwhile training and scuffle a bit with all the totality of the essence of what we are trying to do. As a teacher and mother, I have always known that my job as the “pro” was to make my children independent and responsible. I had to provide knowledge, a few of Carolyn’s head bonks, but with the well-expressed goal of setting the child into a world well-prepared to handle its many unknowns.

I never remember seeing a doctor as a child, as there were none in our tiny town. It was searching out an ob-gyn and pediatrician which gave me my first taste of this kind of medicine. As a young feminist, I sought people who would respect my wishes,work with me especially about the way I wanted to deliver my children and then to care for them. This was pretty typical, and became a model for me. If all patient-physician relationships were more like the mom and pediatrician and ob doc, it would go a long way in this participatory/autonomous world.

Being healthy–thanks to luck and a few genes I avoided–I did NOT see any doctor more than once a year. When I got sick, I trusted that the treating doc knew what he was doing. He did not.

What I and other patients lack is often simple experience of assessing their medical team. I already am autonomous,but need training to work well with my health providers (hate that term…). Whereas I do not expect to have their depth of knowledge, I certainly can learn how to care for myself.

Give me the data, my records, my recommendations, my discharge papers, tell me what to watch in recovery, with the meds, etc. Some simple things!

Peggy

I share Hugo’s concern that we have moved from a goal of autonomy to a focus on partnership. I love Adrian’s comment: “Autonomy is essential to humanity. Without it, we become The Borg.” I have disliked the term ‘participatory’ for some time, as it feels as if I am condescending to allow patients to participate in their own care. In fact, it is the reverse. My patients are allowing me to participate in their lives, which I consider an honor and responsibility of the highest order.

I would like to see the SPM (sidestepping the issue of the name for now) do three things:

*Support (with tools, information, conversation, education, resources) the autonomy of current and future patients as they manage their health and illness with the help o others.

*Support (with tools, information, conversation, education, resources) the collaborative skills of clinicians and others in the health care field, as they learn to help current and future patients manage their own health and illness.

*Model the process of of patient-clinician collaboration within the SPM by working constructively and respectfully together on the above two tasks.

Some of the specifics I would like to see include:

*A true patient medical record, where the patient has full access to the information and tools to use the information and controls who else has access.

*A curriculum for patients, medical school, and residency aimed at teaching patient autonomy and collaboration. This would involve at least history and philosophy, ethics, statistics, communication (especially listening), finding and evaluating evidence, and understanding human behavior and decision making.

*Pressure on institutions to accept patient autonomy as a given.

Finally, I would point out that patient autonomy is permissive rather than prescriptive. It does not require that patients manage their own care, any more than my right to vote requires that I vote. The autonomous patient is perfectly entitled to say: “I’d rather you look at the options and decide for me.”

Peter, this comment from 4 days ago gets my current vote for Best Contribution on this thread. Love it. Useful, relevant, clearly valuable!

I’ve been mostly offline for days, though I was somewhat involved in behind-the-scenes discussions about this post, which arose out of a Facebook thread Hugo amplified this past week, after he’d previously talked a lot about autonomy. (Search “autonomy” on his FB page!) It was obviously time to raise this formally in the SPM community.

I’m so thrilled to see so many voices talking about this.

This is a great discussion and I’m sorry I’m a bit late to the discussion.

Like John Grohol, I don’t view this as an “either or” but “both and.” This creates a false dichotomy. The SPM (and I) have always supported self-care. My view of this is depicted in Doc Tom’s Triangles (see Dave’s post and Alan and Cheryl Greene’s editorial on Doc Tom’s Triangles in the 21st Century).

I think the model represented by the “Information Age Healthcare” triangle is a more nuanced way of thinking about how self-care and health care professionals interact. I certainly agree that individuals need to accept responsibility for being actively engaged in their own health. And they should have all the information and tools to enable them to do so, including full access to their records. This is necessary because, as some of you have noted (and Tom did decades ago), people spend infinitely more time outside the health care system then inside it.

But at some point, most everyone will have to interact with the health care system. When that happens, it is more effective to have a collaboration between the clinician and the patient, with that collaboration being one of information sharing, open communication, and mutual respect. Health care is best delivered as a collaboration.

While autonomy and collaboration must be the default, as some have pointed out (and this is borne out by my years of medical practice), not all patients are willing or able to be engaged in their health or health care. Health care professionals must be able to accommodate them, as well. But that doesn’t mean we should practice paternalistically by defaut.

The “participatory” in the Society’s name has several elements: The patient must participate in their health and care, the health care professional must participate in the patient’s health and care, and the two must participate in the collaboration around the patient’s health.

I agree with Peter Elias’ ideas about what we should do to push our health care system in this direction, and this has been our intent for quite some time (but Peter has done a great job of articulating it).

So which of our members wants to take the lead on one of these initiatives? Nothing gets done without our members’ involvement. Perhaps that the other meaning of “participatory.”

Danny,

> I agree with Peter Elias’ ideas about what we should do to push our health care

> system in this direction, and this has been our intent for quite some time

As I said above, I agree about Peter’s ideas. But I don’t think I can recall any time we actually starting DOING anything about it, right?

Maybe this is the start of a meaningful grass roots project! Peter for Field Marshal! (I’m being goofy in my wording, but I mean it – he’s one of our new Members At Large on the board – maybe he’s presented a practical agenda worth working on!)

John Grohol responded to Hugo by saying “I would also argue there’s nothing in the other definition of “cooperative health care” that means a patient’s autonomy isn’t fully supported. “Cooperate” doesn’t mean “bow down before my decision.” It means, hey, if you’re doing X,Y and Z on your own and you go talk to your doc, maybe you should mention X, Y and Z to them. Why? So they don’t prescribe you a treatment that may be in conflict (or contra-indicated) with those X, Y and Z things you’re doing.”

I think this obviously well thought-out answer perfectly demonstrate what the issue for some of us is.

1/ SPM is timid. And patient autonomy demands an organization that is defined by a lack of timidity.

2/ Patient autonomy is not a by-product. It is the core concept that Tom promoted since the late 70s.

Therefore any definition of PM that doesn’t start with patient autonomy is a blatant watering down of his original ideas. Just reread how the e-patients white paper starts! The first story is of a patient impersonating a doctor to obtain something only doctors could get. It’s a story of revolt not acquiescence.

The autonomous patient is a concept that obviously forces a radical change of attitude from society and timidity is the last thing needed to produce such a change. I am with Hugo. It’s high time to move both beyond and away from the unreadable current definition of PM.

Participatory medicine, as it evolved in the last few years has become so far removed from the daily lives of patients that it can no longer be associated with the self-care model of care that Tom so brilliantly proposed in his now famous inverted pyramid.

It probably explain why the organization which was charged with creating a movement has, 7 years after it was first proposed, a membership in the hundreds with a clear minority of patients.

In life, only facts and hard data count. You can’t have a movement when those you are supposed to represent are not part of the conversation.

Autonomy, or the promise of a system that will truly respect full autonomy is what today’s activated patients want. Anything less is just wishy washy and therefore irrelevant.

Gilles, as always I applaud your passion, though I don’t see eye to eye on all your specifics. Has the time come when you are able to take a leadership role? If I recall correctly (which I might not), every time we’ve had this discussion you’ve declined.

Dear Corine,

you said “It is all about the connection between the physician and the patient.”

That’s not what Hugo is saying. Have a look at his image representing the reality of the life of a patient.

For most of the time, health related issues have NOTHING to do with any doctor.

Thought provoking and powerful. Hugo, as always, your lack of shyness of speaking a different voice is the welcome shout against the echo of group thought.

We don’t need more autonomy in Healthcare. In fact, part of the reason we are having this discussion is because doctors, hospitals, patients, inventors, payers, and business people in healthcare wanted more autonomy in their individual worlds in order to make more money. Autonomy is a basic human right, not specific to only patients, that we each have the right to exercise or not. What we need is a better understanding of the word participation. Participation usually is defined as a unit of time which is right now. I would argue participation should include history and the number of cross over disease community contacts being made. Let me explain.

On October 23rd, I had my right hip replaced. This surgery was a result of having been born with bilateral hip dysplasia which caused large amounts of osteoarthritis. To put it another way, I could not take the pain anymore so something had to change. My left hip went south about 10 years ago at which point I had what’s called hip resurfacing surgery. Due to the left hip experience, I felt incredibly comfortable exploring surgery unlike a lot of patients in similar situations.

My journey towards surgery started in May of 2014 with my pain management doctor. I had incredible relief with synvisc injections with my left hip (rheumatologist at the time did the procedure) and wanted to know if my pain management doctor could do this procedure. My doctor had never heard of synvisc being used in the hip, it’s more commonly used in the knee, but was intrigued by the idea. However, he thought I would have to do a round of steroid injections first and have them fail before my insurance would consider paying for the synvisc. I had tried steroids first with my left hip and had no relief so I wasn’t excited about this possibility.

That June, I had an appointment with my new rheumatologist. Again I mentioned the hip pain and wondered if he could perform synvisc injections. Based on his experience as a doctor he had not had very much success with synvisc and wasn’t keen on the idea of doing it for me. My pain management doctor had ordered an x-ray of my right hip and based upon what the rheumatologist saw he recommended a surgical consult. I wasn’t against surgery; I just didn’t want to have it yet.

While at the rheumatologist he did his usual blood test to make sure my liver was functioning right. Turns out it wasn’t. His nurse, on a Friday afternoon, was the one that called me with the results and recommended next step. I was at work so she left a message. Bad joints don’t scare me, bad liver tests do however. Since I got the message late I wasn’t able to call the office back with any questions or concerns about the test.

The nurse recommended that I only use my anti-inflammatory and Norco sparingly at best. In 3 weeks I was supposed to go back in for another blood test in order to see how my liver responded. Within 36 hours of going on those meds I was looking up the phone number for my surgeon. The meds were obviously doing their job because I had no idea I was in that much pain.

My surgeon, who I’ve known now for 10 years, recommended I see a different surgeon who specializes in basically shaving the hip in order for it to better fit into the socket, pretty much correcting the hip dysplasia. At this point I just wanted a total hip replacement and be done with it. However, I have a lot of respect and trust with my surgeon so I took his advice and consulted with his colleague.

To make a long story shorter, the colleague concluded that my right hip was too damaged and needed to be replaced. It was now September and time to schedule my total hip replacement for October 23rd.

Many reading this might be alarmed at the steps I had to go through in order to get relief. Many probably are not surprised. Personally, I like and respect all my doctors and think they did the best they could considering our health care system. They all engaged me and worked towards reliving me of pain and thus raising my quality of life.

Roughly 4 hours after the operation I was getting myself out of bed and walking. My parents and nurses were surprised at my willingness to attempt to walk. I wasn’t. Despite my relationship ending poorly with my physical therapist due to an unrelated issue, she had taught me well the art of learning to walk again after previous surgeries. In fact, much of my success currently is due to her working with me for roughly the past 7 years. Much of my success is also directly attributed to the skill and dedication of my surgeon. Without his commitment to his profession I probably would not have been able to drive again 10 days after surgery or be able to return to work 2 weeks afterward. I would also be incredibly selfish if I didn’t acknowledge the role that my friends Britt and Julie played in my recovery. Both, along with many many many others, were supportive, compassionate, and engaged care givers in their own way. Finally, I have to give a shout out to my parents who were there from check in to discharge encouraging me every step of the way.

I like to believe that every human was born with the right to be autonomous individuals. We have the right to become independent, unique individuals as we sit fit. The trouble is healthcare took this to mean that hospitals don’t have to work or share new technologies that might benefit the patient. Doctor’s offices have no longer become a place to receive care; they are a bus stop on a continuously moving train. Chronic and acute patients are billed the same despite requiring very different amounts of care. Even something as simple as a medical record is now written in 100000000s of different languages with expensive decoder rings.

We need to reward participation by all parties. We need more cross over design projects. We need more participation by patients in research, education, and policy making. We need more communication from the healthcare industry. We need more participation that is defined as the now but includes the history leading up to the now.

I agree with everything you wrote here Alan, and am saddened to read of your experience. We have so much work to do together. Thanks for sharing your experiences with all of us — and a shining example of far we have to go.

Alan, It’s a real pleasure to meet you. You tell your story clearly, and it’s a compelling illustration of how an informed, capable, thinking patient can be defeated in his/her efforts to be responsible for his/her situation.

A productive thing for us to explore at some point would be the various factors that interfered with your efforts to make informed choice. Should SPM attack various insurance issues? I sometimes rant about them, but that hardly seems to be a priority. Should we attack the difficulty of finding out the full range of treatment options? We’ve discussed that.

A related topic we’ve covered here is the difficulty of finding GOOD evidence in the literature, because so much of it is scientifically weak…. and because so many docs don’t know that. THAT’s ironic, because in a case where a patient is more up to date, physician authority is misplaced.

In any case, as I say, I’m glad to meet you. I hope you’ll continue to be part of our discussions. Clearly the way you present the issues raises questions that are highly relevant.

(Sorry for being late in seeing your comment!)

Hugo, thank you for sparking such an important and thought-provoking conversation. I have found so many of my interactions with the healthcare system alienating over the past 30 years because of the lack of recognition of my autonomy. I find it particularly odd due to my education and training as a lawyer and consultant where I work FOR and WITH my clients. I give them my best professional, often highly technical advice, but they own the decision. I MUST explain things in a way that they can understand and act (not optional, mandatory) or I get fired. I’m not sure why in medicine I feel like I work for the doctor, that the office, the workflow, the language and services are all created to serve him and I am only begrudgingly tolerated if not outrighted maligned as lazy, uneducated, and noncompliant. Not only should my autonomy be assumed, but my “clienthood” and the work on reorganizing the system and the medical culture to serve my needs, limitations, schedules, and circumstances can then begin in earnest.

Donna, thank you for this analogy and great insight.

I agree with Donna’s analogy. (For those who don’t know, Donna is a newly elected board member too.)

I also agree with Adrian’s view that the issue of third party payment royally screws things up – I’ve heard many people on both sides talk about insurance companies denying patients, providers, and sometimes both the authority to do what they want. In those cases, the only one with autonomy is the insurance company.

(Mind you, I’m not painting all insurance companies in all cases as evil. I’m talking about the cases I mentioned.)

Among other things this is why I always buy the highest deductible insurance I can, so I’m free to buy what I want.

The reason lawyers and accountants work as agents of their client and physicians often don’t has a lot to do with “third-party payment”. The payers contract with the physician’s employer. These contracts are secret and both parties to the contract benefit from a lack of transparency of quality and of cost. What could possibly go wrong?

Autonomy for the patient or the physician is the last thing the contracting parties want.

Donna – absolutely love your comment!

We live in a world where health issues are complicated; where there are many options for treatment of a specific health condition; where our convoluted payment system with its lack of price transparency makes it difficult to make educated choices; where finding good health care providers is a challenge. I support and advocate for empowering patients so they will take responsibility for their health, use the tools available to them to become educated and proactive about their health issues and grab the opportunity to challenge, question and defy the health care establishment when it will potentially result in a better outcome.I agree with all those who have expressed their dismay at the patronizing approach that has for so long permeated the physician/patient dialogue. I cannot, however, support the concept of patient autonomy or a system where participatory medicine is no viable.

One of the things that persuades me to support and work on behalf of SPM is the reality of patients, physicians, caretakers, therapists, nurses, NPs, PAs, pharmacists and others working together to seek better health care for patients and better outcomes in the world population. This is a value that has not been well explained and one that we cannot afford to lost sight of. We must be wary of an creating an environment where the autonomous patient becomes as divisive as was the patronizing physician of the past.

Thank you so much for this wonderful conversation. It is all about the connection between the physician and the patient. And we are all people, so we are all different. We vannot crat a handbook for the empowered patient. We can share knowledge, tools and possibilities. For me the key is the empowered, independent patient who takes charge of their own health and care. In whatever form that may be…. and that last sentence is crucial because there are so many ways to be empowered and independent. Also not knowing and admitting is empowered!

Corine, thanks. I agree it’s about the connection between doctor and patient. But that’s only possible during our interactions with the healthcare system, a small part of a patient’s life.

Most of the care happens outside of clinical setting when the patient is left to her own devices. Self-care is the predominant form of health care. That’s why autonomy is paramount.

Thank you so much for this wonderful conversation. It is all about the connection between the physician and the patient. And we are all people, so we are all different. We cannot create a handbook for the empowered patient. We can share knowledge, tools and possibilities. For me the key is the empowered, independent patient who takes charge of their own health and care. In whatever form that may be…. and that last sentence is crucial because there are so many ways to be empowered and independent. Also not knowing and admitting is empowered!

In order to have autonomy we need access to medical evidence. Currently, due to journal paywalls, most patients do not have access to the medical literature. I suggest SPM explore arranging access along the lines of what the Association of Health Care Journalists has arranged for its members. AHCJ members have access to UpToDate, The Cochrane Library, all of the ScienceDirect journals, Health Affairs, the JAMA journals, and other resources.

Marilyn, this is a wonderful idea.

Hugo, thanks for your insight. I agree and think the ideal healthcare relationship model has not been included in the latest reforms – whether ACA or other reform efforts.

As a patient, I usually start with physicians on diagnosing my health and any conditions. Whether it’s driven by insurance, care coordination, or specialist training, I often autonomously (with my family) weigh treatment options and preferred outcomes with potential risks and complications.

At Decisive Health, we’ve developed a web-based tool that facilitates shared-decision making and patient-centered care to help patients and physicians to better work together.

I’d be glad to discuss further or provide demos if there is any interest.

Thanks,

Michael

As a co-founder of the SPM, I can recall the blood, sweat and tears that went into formulating the definition of participatory medicine. We were bent on preserving Tom Ferguson’s legacy as defined in the White Paper, and I was pleased when we arrived at “a movement in which networked patients shift from being mere passengers to responsible drivers of their health, and in which providers encourage and value them as full partners.” Patients as drivers rather than passengers! – that was the clarion call.

I was surprised a couple years later when that definition was changed to the current version and I don’t know who changed it. But with the demise of the old definition it’s indisputable that we lost the perspective of the patient at the center, and so I’m cheered with Hugo’s post and this conversation as a call to return to Tom’s vision.

There is so much that SPM can do by shouldering this burden of advocacy. As a publishing entrepreneur and open access advocate, I’ve decried that medical journals are by far the most closed of all professions, when clearly they should be the most open. So I applaud Marilyn Mann’s suggestion that we explore open subscription for our members – and more importantly, that we get noisy on this subject for the benefit of all patients (since SPM members generally have the ways and means of getting access to the literature one way or another).

This is just one example of where strong advocacy could advance the concept of patients as drivers; patient health records, transparency from A to Z, literacy regarding what comprises evidence, and community resource sharing are profoundly important as well. I’m encouraged that the new leadership will carry SPM in that direction.

For the record, the definition on the website was updated in February 2013 as approved by the SPM leadership at that time (which included Hugo Campos, who sat as a member at large). It was intended to eliminate some of the conflicting definitions of PM and remove redundancies.

So, John,

I expect your response means you and the SPM leadership currently embrace that new definition, which, BTW, is the only one available on this site. Correct?

Let’s repeat that definition, because it’s worth it:

“Participatory Medicine is a model of cooperative health care that seeks to achieve active involvement by patients, professionals, caregivers, and others across the continuum of care on all issues related to an individual’s health. Participatory medicine is an ethical approach to care that also holds promise to improve outcomes, reduce medical errors, increase patient satisfaction and improve the cost of care.”

I wonder how many members of the SPM leadership are able to recite that definition, when asked by people what is Participatory Medicine.

The homepage of SPM continues to also list — front and center — the “traditional” definition of PM. None of definitions of PM currently talk explicitly about getting direct access to one’s medical records, accessing research studies at no cost, or patient autonomy as being the “center” of PM (things all brought up by others in this discussion as being central to their concept of PM).

PM is a lot of different things to a lot of different people. To me, as I’ve repeatedly said, it means being the empowered, independent patient who takes charge of their own health and care. In whatever form that may be.

Ultimately, SPM is what its members make of it. If its members want it to be all about autonomy, I believe that’s what we should be. If its members want it to be all about open access to research, I believe that’s what we should be. If its members want it to be OAuth and all that, I believe that’s what we should be. We are — and always have been — a member-centric and membership-based organization. (I speak for myself — always — not for the organization.)

We spend so much time talking about what PM or SPM *should* be instead of just helping forward the meme of PM in whatever form we believe it works best. I do it every day in my world, and will continue to do so because I believe that an empowered, informed person is a person who will be best able to help themselves. If SPM becomes all about OAuth or open journal access, I’ll continue forwarding the meme I believe in.

I think that all this talk that PM must be a black and white definition is detrimental to our forward movement. The founders of our country realized not everything could be well codified in their original declaration, so they left it to a later constitution to figure out. The writers of our constitution realized that not everything they believed in could be contained within that document, so they left to the Bill of Rights. Wiser people than I realized that not everything could be captured in a static document (or definition) that couldn’t evolve with changing times and needs.

In other words, I believe that PM is an evolving idea we must embrace in all its forms, and continue to build upon. If we only look to the past for the answers, we’d never be able to expand our horizons — or the hopes and dreams for the future of all patients.

John, minus points for the ad hominem. Actually, to set the record straight, a draft of the strategic plan that was shared with me in July of 2012 already included the revised definition. I attended my first board meeting on October 18, 2012, when was discussed the implementation of the strategic plan. The definition predates me.

Granted, I could have done a better job. We all could. I understand the urge to defend the SPM, after all as founding board member and treasurer of the SPM, you have been there from day one.

But I believe it is time for us to recognize our need to grow and allow ourselves to evolve. The time is right. And we need the SPM to lead.

There was no ad-hominem there (meant or implied) — just stating for the record when the definition was changed publicly, and who made up the Executive Committee at that time. Given you said the definition was shared with you in July of 2012 and not updated on the website until February of 2013, that’s a lot of time to discuss it (and raise any objections about it).

To me, evolution means embracing a broad standard that welcomes all comers, no matter what their passion. Whether it be open access to journals, open access to our medical data locked up in hospital (or other health care organizations’) records, open access to our medical device data, understanding what their treatment options are and feeling empowered to choose the one that works best for them, or focusing on the huge impact that self-care has (but that few people seem much to talk about) — or any of a dozen other things that PM is about as mentioned by our members both here and on the listserv over the years.

The moment people start breaking out the argument that you are either X or Y is the moment that, I personally, lose interest in the discussion. We are not X OR Y — We are X AND Y (at least in my own personal opinion).

We often tend to talk about “medical care” at the individual level and focus on what the “patient” can do differently (are they passive recipients of care, participants or autonomous) vs how to change the “system” itself. When you have a systems level problem you need a systems level solution.

.

The providers are attempting to change how they share risk and profits via ACO’s (patients were dropped from the required advisory panels) and there are a patient centered health care systems.

.

There are of course some health models like that found at Group Health Cooperative in the PNW which on paper are owned by the patients (620,000 members) but the more recent Nuka Model in Alaska in which the patients literally redesigned the system itself are transformational and can serve as a national model

“the whole health care system created, managed, and owned by Alaska Native people to achieve physical, mental, emotional and spiritual wellness.

.

The client-provider (not patient nor customer but client/owner) relationship is at the forefront.

Instead of being the objects to which medical services were provided, beneficiaries became the essential partner, metaphorically the managing director, of a series of processes focused on attaining wellness rather than just treating illness. Patients have been transformed into customer-owners.”

.

So rather than focusing on how to change the “behavior” or the “patient” in an existing broken system from passive to participatory to autonomous the pivot might be to change the system itself to one in which we still put relationships first but where the patients become the “owners” of the health care systems and you can design it to meet people where they are on the continuum of passive to autonomous.

John, I’m not sure that “evolution means embracing a broad standard that welcomes all comers, no matter what their passion” – either biologically or regarding SPM. Rather, fitness demands specialized and well-honed traits or memes.

In toiling this past year to define the mission of my own nonprofit startup, Rapid Science, I’ve studied business guru Peter Drucker. He stated that 8 words should be sufficient to state your mission. “The effective mission statement is short and sharply focused. It should fit on a T-shirt. It must be clear, and it must inspire. Every board member, volunteer, and staff person should be able to see the mission and say, ‘Yes. This is something I want to be remembered for.’”

It was in this spirit that the original statement was forged by the co-founders. Here’s my shot at the essence in 8 words: “Helping patients become responsible drivers of their health.” Everything else – the network effect, partnering with HCPs, improving outcomes – reflects the process by which the mission is achieved, rather than the mission itself. We need a multitude of talents, skills and experiences to achieve this mission, but it’s critical that the passions are aligned.

I believe that John is correct: the biggest issue is not the definition. It is the way the SPM has been functioning from day 1 with its members, or more appropriately without its membership. The leadership is totally disconnected from the members and NEVER communicates with the membership. I have never seen an advocacy organization that doesn’t regularly communicates with its members, letting them know what has been happening.

The organization is not interested in getting any input or feedback from its membership. In fact it has no clue who the members are.

Furthermore, the leadership has consistently behaved in ways that have made many well known “doers” jump ship in a matter of weeks because nothing ever gets done, except never ending discussions about why every new idea should not be implemented, all between a small clique.

John’s aggressive defense of an indefensible definition of PM, which permeates the way the world sees the SPM, is totally symptomatic. As I have said before, the only way to save SPM is to have an entire change of leadership, with fresh blood really taking forward the empowering of the patient. Otherwise, it will become even more irrelevant than it has already become.

This irrelevance has become a problem. There must be a strong organization promoting the significance of the autonomous patient. Now that SPM has clearly dropped out of the face of the earth in this regard, what should be done? That’s a real question.

Awesome summary and “elevator pitch” there, Sarah! Thanks for sharing that wisdom. Perhaps a path forward…

How about “Helping patients helping themselves” ?

When I tell others about participatory medicine and the goals of this group, I sum it up by saying that it is the civil rights movement for patients. That seems to explain the issues in a satisfying manner to many people, each of whom may have a different issue which limits them from becoming first-class citizens of their own health. We recognize quickly the positive impact of the earlier civil rights movements,and connect with the idea of the benefits and responsibilities that were engendered by those movements.

Just use this phrase to your friends and co-workers–the “civil rights for patients”–and see the instant acceptance of the idea of participatory medicine. Not only does it engage the others, it reinforces my own sense of mission to other patients.