How can laypeople find up-to-date, trustworthy answers to questions they have about living safely in an emergency, when they have them, in a useful manner? Part 1: a person-first approach for researchers & content creators to help people and their communities find trusted guidance to answer their questions about living safely in a Covid-19 world.

What could go wrong?

All of us, from laypeople to professionals – you, me, and our communities – were totally unprepared for this novel virus with global and household impacts. Now, every single day we try to drink from a firehose of new information with the clean information mixed in with the suspect.

All of us, from laypeople to professionals – you, me, and our communities – were totally unprepared for this novel virus with global and household impacts. Now, every single day we try to drink from a firehose of new information with the clean information mixed in with the suspect.

Even researchers who deal in information as their profession find it difficult to manage the deluge of information – to keep it clean, clear, current, and relevant. We all find ourselves overwhelmed, confused, anxious, and mistrustful. AND we all drink from different hoses, some more trustworthy than others. Question: How can those researching, writing, and sharing information about Covid-19 help people and their communities find guidance informed by research that answers their questions on living safely?

Let’s consider one scenario about one household: Carlos, 52, an ICU nurse, buses to work where he cares for COVID-19 patients. His sister manages her chronic arthritis pain as best she can while caring for their mother, 80, who can’t be left alone – she’s suffering from early dementia. His sister takes their mother to the local Senior Center’s respite program. They worry about what would happen if Carlos brings the virus home from work. They worry about the risk of infection to his sister and mother as they travel back and forth to the Senior Center. They wonder When do we need a COVID-19 test? Which test? How often do we need to get tested? Who pays for the tests? What do we do if one of us is positive?

Let’s consider one scenario about one household: Carlos, 52, an ICU nurse, buses to work where he cares for COVID-19 patients. His sister manages her chronic arthritis pain as best she can while caring for their mother, 80, who can’t be left alone – she’s suffering from early dementia. His sister takes their mother to the local Senior Center’s respite program. They worry about what would happen if Carlos brings the virus home from work. They worry about the risk of infection to his sister and mother as they travel back and forth to the Senior Center. They wonder When do we need a COVID-19 test? Which test? How often do we need to get tested? Who pays for the tests? What do we do if one of us is positive?

The research industry tends to invest in answering questions arising from acute and emergent medical situations – drugs, therapeutics, procedures, devices, and behaviors. Lay people and communities tend to have questions about function, employment, caregiving, school, transportation, cost, and navigating the healthcare system. So, different priorities and often very different firehoses of information.

Who are we writing this?

We are a small band of volunteers who met through a CDC initiative called Adapting Clinical Guidelines for the Digital Age. We are clinicians, patient-caregiver activists, scientists, and data geeks – and of course, we are also parents, children, partners, neighbors, colleagues, patients, and caregivers. During any crisis and especially an epidemic, people first identify as family and community members. Next, people identify by their skills, occupations, experience, and credentials: clinicians, scientists, employees, bosses, etc. So, that’s who we are chewing on this awesome dilemma. We met to consider the impact of COVID-19 on laypeople and their communities, our communities. We were commiserating: Our families, friends, and neighbors were seeking us out to answer questions they had about living safely during this pandemic. What did we know? How would we advise them? What should they do? They sought us out because we were relative experts, meaning we may have had about a 15-minute advantage on them, but really no more. This small band of volunteers partnered with similar experts who focused on COVID-19 in acute care and medical office settings. Those partners rightfully prioritized saving lives and managing medical care. We knew, however, that most health decisions, in fact, most COVID-19 decisions would be managed entirely outside of medical settings. We gravitated toward that gap.

Our approach to filling the gap. (Finding our audience.)

As otherwise over-committed sailors in wildly under-explored waters, we needed as clear a vision of our destination as we could muster. We knew that our existing appreciation of the concepts around patient-centered care was insufficient, so we needed a more nuanced definition. Next, who, specifically, were our end users? End users are the people who eventually use the tools we begin to develop. Who was our audience? The audience is people who would partner and collaborate with us and may have already developed valuable tools and methods. We don’t want to recreate the wheel. What would be our ask? The ask is the actions we hope this series motivates you to do right now. What would a map look like? What work products should we, could we create?

Patient-centricity, person-centered, person first

Everywhere we go we hear patient-centered this and person-centered that. What does it even mean? In short order buzzwords wear thin (think patient engagement, silos, gig economy). Don’t get us wrong, we wholeheartedly support efforts like the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) and the Patient-Centered Clinical Decision Support-Learning Network. We endorse the IOM (Institute of Medicine) definition for patient-centered: “Providing care that is respectful of, and responsive to, individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.” Immediately, we became overwhelmed by the breadth and complexity of COVID-19 and the diversity of individuals and communities affected. Everyone’s preferences, needs, and values is daunting. To manage, we needed to understand significant characteristics of that diversity in relation to COVID-19 Safe Living. So, for purposes of this work, let’s start with understanding people and hearing their questions and concerns and then move into the IOM definition.

We are person first.

Who are we doing this for? (End users.)

Appreciating the tremendous diversity of laypeople, we determined that everyone was too big a target and that it is presumptuous to think we could have a profound understanding of all communities. Perhaps people who help people in their communities could be our end users – patient and caregiver advocates, leaders in peer communities, lay experts (think 15-minute advantage). Let’s call them community resources.

Partnerships, resources, collaborators. (Our audience.)

Since this small, mighty band of volunteers started out by meeting in the computerized clinical decision support (CDS) space, we wanted to enlist our colleagues to expand their view of CDS and work with us. So, our audience became the CDS and research industry and stakeholders including patients, caregivers, clinicians, and communities. As an example, Datavant and many other organizations assembled the COVID-19 Research Database in an effort to make real-world data available to researchers to better understand and mitigate the pandemic. Anyone can submit ideas for questions they think researchers should investigate. To incorporate the layperson’s perspective, we worked with Datavant to provide a list of research questions that we crowd-sourced from friends, family, and colleagues, including

Since this small, mighty band of volunteers started out by meeting in the computerized clinical decision support (CDS) space, we wanted to enlist our colleagues to expand their view of CDS and work with us. So, our audience became the CDS and research industry and stakeholders including patients, caregivers, clinicians, and communities. As an example, Datavant and many other organizations assembled the COVID-19 Research Database in an effort to make real-world data available to researchers to better understand and mitigate the pandemic. Anyone can submit ideas for questions they think researchers should investigate. To incorporate the layperson’s perspective, we worked with Datavant to provide a list of research questions that we crowd-sourced from friends, family, and colleagues, including

- Who needs a Covid-19 test?

- How long after I test positive do I have to be quarantined?

- How much will a Covid test cost me?

- If a test shows that I have antibodies to Covid-19, am I safe?

What does a home run look like? (The ask.)

Why do this work? Why explore something we know we can’t finish? This mighty band of volunteers has neither the bandwidth nor the resources to sustain this journey. Our goal is to open a door, interest – no, excite – people to come on board, work with us, and carry it on to a sustainable conclusion. We don’t know what the end might look like. So, once again, we want laypeople to be able to find evidence-informed guidance they can trust about challenges in their community, like COVID-19. A home run would be finding someone, some people, dying to grow this discovery process, find funding, build or join coalitions, develop, disseminate, and implement tools and methods – move it along.

Roadmap

In the next section, we introduce the first stop in our journey: identifying personas. In subsequent posts and episodes, we discuss other stops.

In the next section, we introduce the first stop in our journey: identifying personas. In subsequent posts and episodes, we discuss other stops.

Personas. (Person first)

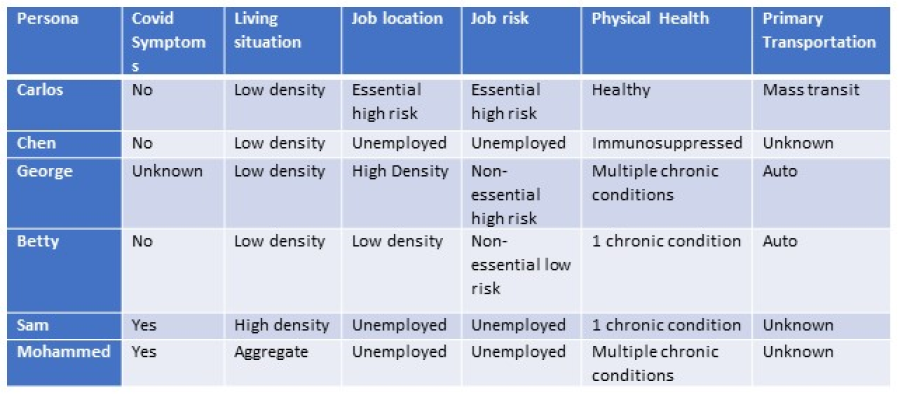

To start with people while respecting diversity, we realized that we needed to create personas, characteristics common across many different groups of people. We landed, unscientifically, on density of living and working, presence of symptoms of COVID and high-risk existing conditions, job risk, and geography as persona characteristics and developed seven different personas including Carlos.

To start with people while respecting diversity, we realized that we needed to create personas, characteristics common across many different groups of people. We landed, unscientifically, on density of living and working, presence of symptoms of COVID and high-risk existing conditions, job risk, and geography as persona characteristics and developed seven different personas including Carlos.

What’s next? (More questions, some answers.)

In summary, to hit a home run, our mighty band of volunteers hopes to find someone, some people, dying to grow this discovery process, find funding, build or join coalitions and move this project along. In subsequent posts we will continue to share our unfunded journey of discovery. We will consider the questions people have about safe living, the gaps in evidence-informed guidance, the challenges of finding what’s needed, when it’s needed, in a useful and trust-worthy manner. Part 2 covers Questions, Gaps, Findability and we move on to Trust and Recommendations in Part 3. In Part 4 we will likely interview current and potential partners working on aspects of this challenge. We seek to promote a dialog within the research community and between researchers and laypeople and their communities. Here we are planting a seed for person-first.

Want to enroll somehow? Know of a place for us to cross-post our print, video, or audio stories? Communicate with us here info@safeliving.tech, #safelivingpandemic on Twitter, or https://www.safeliving.tech/

Recent Comments