For decades, policymakers, CEOs, politicians, doctors, nurses, healthcare workers, caregivers, and anyone who’s been a patient inside or outside a hospital has known one simple fact — the US healthcare system is broken.

Every other first world country has long figured out how to provide affordable healthcare to their citizens. The US, on the other hand, has only figured out how to create a complex, complicated “system of care” (which is not a system and certainly not one of caring) that manages to bankrupt thousands of Americans each year, offers sub-optimal care in numerous cases, and angers nearly everyone who is forced to participate in its lunacy.

Despite these problems, vigilante justice is not the answer to fixing our broken system. What we can do is change the US healthcare system through reform and expressing our frustration with the misaligned profit motives that value profit over healthcare.

How we got here

We can partially blame a well-meaning man by the name of Abraham Flexner. Flexner was what we would now call an education reformer. In 1908, he examined the state of the US college system that attracted the attention of the powerful Carnegie Foundation. The Foundation commissioned a similar report on medical education — now known as the Flexner Report — which he released in 1910. Flexner was not a physician. but nonetheless his report led to wholesale and large scale reform in the education and training of doctors in America. It brought European professionalism to the practice of medicine in America.

Many schools serving African Americans and women were closed, exacerbating racial and gender disparities in medical training and healthcare access. Reducing the number of physicians graduating from schools also resulted in a shortage of physicians, which began the long, slow progression of raising healthcare costs for all Americans.

Flexner also was not an economist, but he proposed a new economic system of reimbursement for physicians in his report. His fear, grounded not in any systematic or scientific data but just anecdotes of the times, was that physicians were economically motivated to provide unnecessary care to their patients, since patients directly reimbursed doctors for their services. He recommended a third-party payment system to reimburse physicians and other healthcare workers as salaried workers via non-profit hospitals, to take the perceived conflict of interest out of physicians’ hands.

Flexner also was not an economist, but he proposed a new economic system of reimbursement for physicians in his report. His fear, grounded not in any systematic or scientific data but just anecdotes of the times, was that physicians were economically motivated to provide unnecessary care to their patients, since patients directly reimbursed doctors for their services. He recommended a third-party payment system to reimburse physicians and other healthcare workers as salaried workers via non-profit hospitals, to take the perceived conflict of interest out of physicians’ hands.

World War II again altered the landscape of providing medical care in the US. Wage controls led employers to offer health insurance as a benefit to attract workers. This system persisted after the war, cementing employer-sponsored insurance as the dominant mode of coverage in the US. Unlike European countries, where social insurance systems emerged after WWII (like the UK’s National Health Service), the US instead relied on private insurers. This created a fragmented system where coverage and costs varied significantly across the population.

Non-profit hospitals now had access to larger financial resources, too, due to insurance premiums now being paid to them by employers on a consistent basis. People were not only cut off from directly paying for their individual healthcare charges, they also had no understanding how much anything healthcare-related actually cost. This was all baked into the US tax system and codified over the intervening decades.

Naturally, this is a grossly simplified overview. The history of medical practice in America is complex, but if you needed to identify the point where a sea change took place, it was after the release of Flexner’s report.

Where we are today

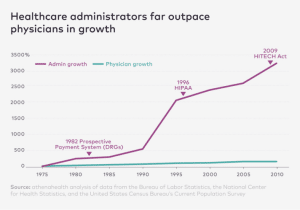

With two competing corporate organizations competing for healthcare dollars now — insurance companies and hospital systems — physicians and patients were all but written out of the economic system. Yes, physicians provide care to patients, but all the finances tied to that care are purposely opaque. With this opaqueness comes complexity, and the need for ever more staff to make sense of it all. Insurance premiums and administrative costs skyrocketed to address this need, but also because nobody knows what anything truly costs in US healthcare.

“Approximately 7.3 cents on every dollar actually goes to a physician who provides all the care,” says Kian Mondolou, MD, a transplant surgeon. “So the vast majority of money isn’t going to doctors. And when they say, ‘Oh your surgery costs $10,000, it’s not the surgeon that’s making $10,000.”

Health insurance companies are set up to ensure employers are only paying for “needed” medical care. However, they alone decide what is truly needed, based upon criteria checklists that are all driven by opaque algorithms. It is likely few C-suite executives even understand their own company’s algorithms, but these systems ensure health insurance companies make money for their shareholders. Actually paying for healthcare costs is a secondary concern, because the less they pay, the more value shareholders receive (and of course, the large the bonus checks are for executives and managers).

Make no mistake about it: health insurance companies like Cigna, Elevance, and UnitedHealth Group make billions of dollars in profit every single year. And not small profits, either — between $5 and $22 billion. Each. Why should a company that is acting as a glorified bookkeeper be allowed to make so much money where the incentives to actually provide less care in order to make more profit are completely backwards from a system most Americans want? Should healthcare be a profit center that profits even more by denying you care when you get sick?

As Scott Carney puts it his video below reviewing the state of American healthcare, “It’s so monumentally messed up that most Americans feel basically powerless in the face of the historical and economic exploitation that has landed us as hostages to insurance companies.”

Innovators can’t innovate without the data

It’s really, really hard to innovate in a field when you don’t understand the data. And in healthcare, there is very little financial transparency. This is by design. If physicians and patients figured out how to simplify the complexity of the American healthcare system, they might understand that cutting out all those administrative costs would greatly reduce the cost of care.

Steve Case & Revolution Health Group

A few people have tried. Steve Case, the billionaire founder of America OnLine (AOL) launched a company called Revolution Health Group in 2005. A part of the company’s launch announcement noted that, “Most people don’t feel like empowered customers, they feel like a peripheral part of the process, with seemingly everybody but them being able to make the decisions that most impact their lives and the lives of their loved ones.

Over the past year, Revolution Health has been working behind the scenes to create the first comprehensive, consumer-driven health care company, designed totally around meeting the needs of consumers and giving them more choice, control and convenience.”

Nothing came from his vaunted efforts and he sold the company in 2008. One of the driving forces for this failure was the inability to access and make use of the financial and usage data that the company could then innovate around. For instance, where could technology be put to better use to free up a healthcare worker’s time? Or, where could we streamline paperwork or record keeping or financial reimbursements to take some of the friction out of the system?

Mark Cuban and Cost Plus Drug Company

Others have had more success. Mark Cuban launched a public benefit corporation called Cost Plus Drugs in 2022 to help address one small part of the healthcare system — the price of prescription medications. Consumers in the US pay the highest prices on medications in the world. This is due to a multitude of factors, but administrative and marketing costs are a large component of this higher drug pricing. (The other major component is that US consumers are financing research for new drug development for much of the rest of the world.)

Cost Plus Drug Company seeks to lower the cost of popular medications for US consumers. It cuts out pharmacy benefit managers, just another administrative layer in the already heavily administratively-laden healthcare system. Pharmacy benefit managers provide very little benefit to anyone, yet they’ve marketed themselves as necessary to the system. Cost Plus Drugs demonstrates this to be patently false. According to Wikipedia, they now offer over 2,200 drugs and “the drugs are sold for a price equivalent to the company’s cost plus 15% markup, a $5 pharmacy service fee, and a $5 shipping fee. The company ships to all 50 US States.”

Innovators have had a famously tough time with healthcare, however. Nibbling around the edges of the system seems to provide some value for the amount of reform effort required.

Time to kick out people who have no business in your healthcare

What the killing of Brian Thompson, the UnitedHealth Group’s CEO, demonstrates is the level of frustration many Americans experience with the current US healthcare system. While the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (also known as “Obamacare”) was a valiant effort to fix some of the problems of the system, it improved some things while making other things worse. Yes, more Americans have (deplorably substandard) coverage due to the law, but insurance companies found even more ways to earn even more profits through loopholes in the law.

As long as for-profit companies are allowed to operate in the healthcare space, they will always focus on increasing shareholder value and executive pay over ensuring value for every healthcare dollar spent. Profit is always going to be a more motivating force than good will — or even following the law — in a capitalistic system.

Non-profits and public benefit corporations are not cure-alls, but they are a step in the right direction. While profitable non-profit hospitals have taken their windfalls and poured it into building new facilities (that in many cases are unneeded and meant to reward the most profitable parts of their operations), they can be managed through new incentive structures and new laws to focus more on transparency in pricing and increasing the focus on patient care. Colleagues have actually compiled a list of possible ways to reform the US healthcare system.

Such reforms wouldn’t be easy and without pain, especially to the insurance companies. But it’s high time for Americans to kick out people who have no vested interest in your healthcare — shareholders, administrators, managers, and highly-compensated C-suite executives — and get them out of the partnership patients have with their physicians. This should be a one-on-one relationship that values respect, listening, and collaborating together on the patient’s care. It is not a place to look to monetize every minute of the physician’s time, or to eek out every dime on placing a bandage on someone’s wrist.

It’s high time Americans be heard. It is, after all, your health on the line.

Your Health, Your Voice. Be informed. Get involved. Demand to be heard.

#YourHealthYourVoice

Good blog, John. I’d like to tie your words more tightly into the idea of participatory medicine. Systemic changes in how health services are funded would certainly (hopefully!) improve the quality of health care we get. Those changes could be made, however, and still leave the issues of patient participation in their own health care decisions (decisions made at the clinical level from the git-go, not just at the “lifestyle” level when patients have walked out the clinic door)… Patient participation in their own health care decisions is another critical factor in improving health care delivery. This could benefit doctors and nurses almost as much as patients. I think this would be not just a procedural change or an economic change for health care, but a change to the entire culture of health care — a much larger order, because it calls for a change not just in what people do, but in how they think.

I’d be interested to know whether countries who have universal health care also have a better track record with participatory care. From what I’ve heard from a few non-U.S. folks, the answer is “No, they don’t.” Do you have any information on this, John?

This article is well written and has offer much trueful information associated with our current Health Care System, but what it doesn’t share is – how to fix it. Facilities need to certainly “kick-out” those who have not business in daily operations, but those who do need to know what is causing the high costs to begin with. Inventory Management and Design Development Practices need to change to reflect inventory as an asset not an overhead. That begins with moving away from our current policies and procedures in Best Practices and put “boots-on-the-ground” as to addressing the management of our assets, both from acquiring (costs) and storage for JIT designs that will bring true sustainability. Sustainability begins now – not tomorrow!