Stephen Wolfram’s essay, The Personal Analytics of My Life, begins:

“One day I’m sure everyone will routinely collect all sorts of data about themselves.”

A Pew Internet survey suggests we have a long way to go: a September 2010 survey found that 27% of internet users age 18+ track their own health data online. There may be more self-tracking happening offline — please post any measures of that phenomenon in the comments.

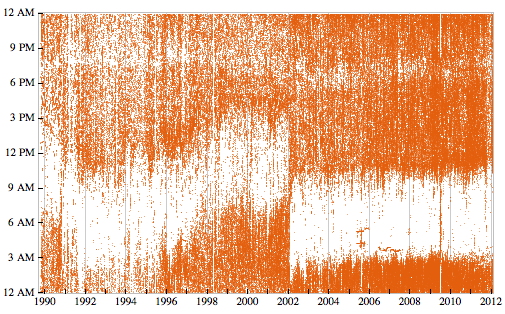

I was intrigued by Wolfram’s extensive use of his own data exhaust such as email time stamps, calendars, pedometer readings, and keystrokes. He feeds it all into Mathematica, a computational analysis platform, which generates amazing results that no human could create, such as this plot of about 300,000 emails:

One aspect of his data collection is extremely high-touch: 230,000 pieces of paper that have been scanned in. Yikes — who did that job? He also keeps an online scrapbook/timeline, but does not appear to keep a time diary, relying instead on automagically-generated time stamps to tell him when he’s been working. I’ve been on guard against such diaries after reading “The Test of Time: A busy working mother tries to figure out where all her time is going,” by Brigid Schulte, which resonated with me and many of my working-mom friends.

Looking at Wolfram’s analysis, I wondered if he and his systems could help Schulte do a better job of tracking how she spends her time. I also wondered if she would be envious of his freedom (he admits to working until 3am and rising at 11am — not exactly helpful during those get-the-kids-off-to-school hours).

One of the central themes of Schulte’s article is that she is too busy to make time to figure out what she does with her time. Reading her account of life, you get a sense of a Mars/Venus divide – men are out on the patio enjoying a cigar and contemplating their personal time-use philosophy while women clear the table, sweep the floor, get the kids to bed, and frantically send emails about the next day’s meetings.

I did a quick search for more insights on this Mars/Venus divide and found Matthew Cornell’s post on the Quantified Self blog, Is There a Self-Experimentation Gender Gap? His rough analysis of QS comments, videos, and in-person meetings found a clear difference in participation: about 80% men, 20% women.

Christine McCaull echoed Schulte’s complaint in her comment:

…I’m just too damn busy to measure almost anything regularly except my bank balance, which is calculated for me. Like most women, I’m on a triple shift life plan. I work, I write, I keep a house and raise a big family…

And yet proponents of self-tracking in health need everyone to engage in it and see its worth, not just people with the leisure (or the extreme motivation of a life-changing diagnosis) to do so.

I went back to our data to see if there is a gender divide when it comes to health tracking online. Yes, there is: women are more likely than men to do it.

Breaking it down into the two categories we asked about, we find that 18% of women track their weight, diet, or exercise routine, compared with 13% of men. Twenty-one percent of women track some other health indicators online, compared with 12% of men.

I would love to add more self-tracking questions to our next health survey, such as additional categories or follow-ups to the two questions we asked in 2010. We’ll be in the field in August-September 2012, so please post your suggestions in the comments or email me later (sfox at pewinternet dot org).

I’m also curious: do you track any aspect of your life? Has it made a difference? Would you be interested in the level of self-quantification that Stephen Wolfram has pursued (assuming you also have the same awesome tools)?

Oh, MAN do you get in my head.

I’m on the run today (“ibid,” one might say, pointing to your post) but I want to say that after more than a year of trying to self-track, I’ve concluded that the ONLY way something will get any widespread traction is if it’s automatic.

Fitbit, Withings scales and BP monitors, Zeos – passive data collectors, yes. But among those, only the Withings devices also *upload* automatically.

A second thing I’ve been mulling, as I try to change my own behavior, is that the bitchiest thing about any substantial behavior change is that it requires rearranging life: removing one thing to make room for another. That argues for things being woven into existing things – e.g. a “walkstation” instead of new appointments to visit a gym. And that’s why I think the future of self-tracking is Automatic Or Quit Kidding Yourself.

Just like the bank balance, which computes itself automatically.

Gotta run – please post more often, because it clears my mind when you do. :)

p.s. *Exactly* the same applies to integrating all those feeds. Right now it’s virtually impossible. When they all get combined automatically, a la Quicken or Mint.com, then we’ll start getting somewhere.

Until then I expect we’ll never have the critical minimal mass of data to create a robust ecosystem of analysis tools. And without analysis tools, there’s not much use for the data – it’s just a geek’s hobby.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that, heh. It just doesn’t change much of anything.

It’s amazing what Wolfram has done with his data, but very few people have the resources and the motivation to pursue that level of tracking. Or at least they didn’t in the past. Self-tracking will get much easier (more passive) and inexpensive, which is what will ultimately bring it to the masses.

In some ways, self-tracking is already becoming popularized. For example, popular devices like the Fitbit have made it far easier to self-track with minimal effort. As the technology improves, self-tracking has great potential for healthcare.

I personally plan to increase self-tracking as new tools become available, and I’d be very interested in seeing additional questions about self-tracking in your health survey.

Thanks, Dave & Rahlyn!

I’d love to hear from more people about how they’re using self-tracking tools.

I’d also love to get feedback on the survey questions we’ve fielded – and topics people think we should add. Don’t worry about getting the wording just right – we can handle that.

In case it’s useful, here are the two questions we asked in Sept 2010:

ASK ALL INTERNET USERS (Q6a=1 or Q6b=1):

Q24 Apart from looking for information online, there are many different activities related to health and medical issues a person might do on the internet. I’m going to read a list of online health-related activities you may or may not have done. Just tell me if you happen to do each one, or not. (First,) have you… [INSERT ITEM; ROTATE]? (Next,) have you…[INSERT ITEM]?

a. Signed up to receive email updates or alerts about health or medical issues

b. Read someone else’s commentary or experience about health or medical issues on an online news group, website or blog

c. Watched an online video about health or medical issues

d. Gone online to find others who might have health concerns similar to yours

ALWAYS ASK e-f TOGETHER, IN ORDER

e. Tracked your weight, diet or exercise routine online

f. Tracked any other health indicators or symptoms online

CATEGORIES

1 Yes

2 No

8 (DO NOT READ) Don’t know

9 (DO NOT READ) Refused

OK, to be clear, it’s 1 question with many parts, 2 of which I highlighted in this post (items e and f).

For those people who like to “know what’s going on with their body” and don’t feel the need to share this information with their doctor…the future of self measurement is great – with the right applications.

On the other hand, for those who are doing it to share with their doctor in the hopes that together they can use the data to monitor their progress towards a goal…don’t hold your breath.

As Dave said, the docs don’t have the technology to “take in” such data: 1) there’s no way for all the disparate apps to interface with the doc’s IT (if they have any), 2) docs are drowning in data already and 3) patient entered data is suspect in terms of quality – not to mention few EHMs have fields for patient self entered data.

There’s also the question of why most health apps have such as short useful life before people stop using them??

Steve Wilkins

I had to go have a little lie-down after I read about Wolfram’s data collection. My first reaction: “Really? Seriously?” Should this extreme obsessive-compulsive – dare I say, narcissistic? – navel-gazing quantified-selfing behaviour even be encouraged?

As for Steve’s question about why people tend to stop using health apps: I suspect this may simply be the nature of the beast. It’s the same story with all those exercise bicycles, Thigh Masters, yogurt makers and other must-haves now collecting dust down in the basement that we were at one time all fired up about, convinced that THIS TIME we will actually USE all of these to get healthy once and for all!

Sigh…..

“I had to go have a little lie-down after I read about Wolfram’s data collection.”

Carolyn, I cracked up on the street when this comment came through on my phone yesterday. Thank you!

I think a lot of people share your perspective, which is why I decided to write this post. I’m fascinated by overboard, potentially OCD self-trackers – we can learn from them and their inventions, ideas, tools, etc. But I’m even more intrigued by the possibility of a tipping point in self-tracking, when it will go wide.

Hi Susannah,

Hope you didn’t have a snoutful of espresso when you cracked up . . . ;-)

I too am very interested in where this tipping point lies. But I’m guessing that publicity about Quantified Selfers like Wolfram will merely serve to utterly turn off the average person (who might actually benefit from tracking health-related behaviours).

There’s a big difference between using your pedometer to help motivate you to track those 10,000 daily steps, or tracking your day’s food intake a la Weight Watchers – and obsessively tracking things like individual keystrokes on one’s computer. That kind of behaviour is so profoundly nerdy that it may just serve to alienate those who are sorta kinda thinking about tracking.

I have tracked data from time to time when a problem occurs that my health care providers and I can’t solve.

For example I tracked by blood pressure and meds dosage for about 6 months last year to figure out what was causing the blood pressure to spike.

I used several apps but in the end a pencil and paper graph with several lines was the most helpful.

(Although one doctor wouldn’t look at it, but that is another story!) My PCP now includes my charts in with the official one.

I do belong to Patients like Me and record evaluations of drugs with other members. That information is really helpful.

Finally, I do weight myself daily. I struggled with my weight for many years but have been at goal for about 22 years. The daily check helps keep it in check. But I will not track that on any website no matter how secure!

Thanks, Elizabeth!

May I ask, just out of curiosity, was the doctor who refused to look at your self-tracking data a specialist or your primary care physician at the time?

Your comment about weight-tracking reminded me of a post I wrote in 2009:

“David Williams of PatientsLikeMe talked about how the extremely detailed, open-access patient data that people share on the site is printable (for doctor’s visits, for example). He said that data sharing confers status on the site and encourages empathy among participants. The instant mood tracker can even head off a flame war since everyone can see that a cranky comment on a forum is coming from someone who is, at that moment, in a bad mood. However, David pointed out that people may post all manner of extremely personal details, even sexual dysfunction, but are often coy about posting their weight.”

http://pmedicine.org/epatients/archives/2009/01/doing-our-best-to-blow-your-minds-emerging-trends-in-chronic-disease-care.html

Its funny… I am in the industry and tend to try apps on myself to understand how the market is evolving, but when I truly need to self-monitor I have always turned to pen and paper. Most recently, taping a blank piece of paper on the wall next to my scale so I can track my weight daily. And frankly it works for me. I also find we suffer from mission creep. I used “Lose IT” for a couple of weeks to track my diet and weight. While its a comprehensive and effective tool, it was way too much to keep up with for the longer term. Unless my toilet starts capturing and uploading multiple data points for me, sticking to the 1 metric that matters most to my situation is the best answer. KISS.

Thanks Susannah for your post and for the work you are doing thinking about what self-tracking questions might be useful for the next health survey. In working with and among pioneering users of self-tracking tools I’ve observed a diverse set of motivations and practices, and it would be great to get some survey data both on how widespread these practices are, and on the dynamic processes of increased self reflection and openness to learning that seem to go with them. Here are some things I am curious about. I write these not as survey questions (that is an art in which I’m untrained!) but just to share topics that I think are interesting.

*Do you collect/track any kind of personal data, such as your weight, sleep, activities, purchases, exercise, health symptoms, etc.?

–List:

*Do you use your computer or phone for self-tracking?

*What are your reasons for self-tracking:

-General curiosity

-Fitness and/or general physical wellbeing

-Improve mood and/or general mental health

-Achieve a specific goal, such as weight loss, better sleep, etc.

-Find a diagnosis for a puzzling medical condition

-Other?

*Do your share your self-tracking data with anybody?

*Do you intend to start a self-tracking project?

*Have you abandoned a self-tracking project? if so, why?

*What self-tracking tool(s) would make your life easier?

*Have you ever brought self-collected data to a doctor? Was it useful?

*Have you tracked side effects to medication you are taking?

I’ve read the other comments to your post; interesting as always! I’ve noticed that the practices of advanced users often produce strongly negative responses, including off-the-cuff diagnoses of narcissism or OCD disorder. This is an honest reaction, and I think worth looking at what feels dangerous or creepy here. While it is absolutely true that there is probably greater neural diversity in the population of advanced users than in a random sample of adults, I don’t think narcissism or OCD is really adequate, either as a diagnosis or as a looser analogy.

What I’ve noticed about pioneering self-trackers is that they have abnormally high curiosity about “the way things work.” There is something that seems dangerous, perhaps even creepy, about staring unblinkingly at highly personal aspects of our life. Virginia Woolf’s famously expressed contempt for the indecencies perpetrated by James Joyce (“a queasy undergraduate scratching his pimples”) is perfect expression of this feeling.

This isn’t necessarily the place to do it, but I think such reactions deserve more thought, and I always like to point them out and underline them.

Thanks, Gary, for the detailed survey suggestions, the Woolf quote which I now can’t get out of my head, and the description of QS folk as people who have an “abnormally high curiosity about the way things work.” That makes sense to me.

I’m reminded of one of your earlier posts about people sharing health information online, and one of my comments on that post about the perceived social acceptability of the dimension of health being shared (or sought) – e.g., sexually transmitted diseases vs. heart disease.

I suspect shame plays a more significant role in the sharing of tracked information than in the tracking itself, and suspect that women are generally more likely to be ashamed of (or embarrassed by) their weight than men are.

As for the Stephen Wolfram article, I didn’t get the sense that he is particularly embarrassed by anything revealed about his quantified self.

If you’ll be going back into the field to track self-tracking, it may be interesting to differentiate tracking from sharing … and perhaps breaking down the granularity of sharing, e.g., private, semi-private (friends) vs. public.

While I’m commenting (and you’re seeking input), I want to put in another plug for differentiating health tracking from illness tracking, i.e., quantifying one’s level of fitness vs. quantifying one’s level of disease. I suspect there is a greater proportion of runners publicly sharing their running logs than, say, MS patients publicly sharing their flareups on PatientsLikeMe (or doing so via their real names).

Finally, on a related note, I wanted to share what I consider to be an outstanding and inspiring example of a woman who has been willing to track and visualize her illness symptoms in a public forum: Katie McCurdy’s blog post about medical history timeline: a tool for doctor visit storytelling. Although the data she used was based on memory, I think that the more people can personally benefit from the tracking of symptom data (vs. [only/primarily] drug companies benefiting from that data) the more willing they will be to collect that data.

Joe, there is an *essential* difference between tracking & sharing – thank you for pointing it out.

Everyone – click thru to read Katie McCurdy’s post. Beautiful expression of what we’re talking about here.

Back in 1997, before mobile became popular, I predicted that laptops plus lab coats meant “the practice of infomedicine will inevitably become the mainstream method of making medical decisions.” (See: http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/1998/net_98/logo1005.htm)

What is happening now through mobile devices, point-of-care decision tools, remote monitoring and every other kind of web-enabled tech is that the classic primary care doctor model is being blown up.

There will be no alternative but a participatory medicine that sees the physician as one key member of the clinical team and understands that the medical evidence, the clinicians’ experience and the patient’s values and preferences all are necessary components of high-quality care.

Thanks to so many who are leading this transformation “in the trenches.”

Some great insights here Susannah. I’ve beent thinking about Stephen Wolfram’s post and your wonderful follow up for a few days and I just wanted to share a few of my thoughts.

Like you said in an earlier comment reply, there is a lot to be learned from people like Stephen. He’s obviously a brilliant mind and exceptionally skilled at the intricacies of data analysis. But, I think we place too much emphasis on the act of tracking when se express surprise and bewilderment when we see how much data he has collected. With the possible exception of his daily steps everything he collected was done without his direct involvement. Email logs, keystrokes, call data. All of this is passively collected in the background. Heck, if you use gmail, those email records are being housed somewhere for you too (access and analysis is a different story). What I find exciting about this, and the possible implications in the health sector, is that passive data collection is becoming much easier and much more common. We live in the age of the data-base, forget the internet era, our actions are constantly being collected and stored. And unlike some people I am more excited than fearful about this.

Why am I excited? Because with data and a little bit of work you can create information. And when you are able to connect bits and pieces of information you can create knowledge. This is where the biggest improvement in our lives will come from. Self-tracking has always been around, but it’s just been hard to do. Now we have technology doing the tracking for us and maybe that can free us up to focus more time on information generation and knowledge exploration. We know so little about ourselves and how we truly interact with the world around us. From a biological to the psychological we are still very unsure of how it all works. Generating more data might be a great way to help us think about and possibly figure out some of those interesting connections.

I guess that was a bit of a long-winded way to say that we should focus less on data collection, but on what happens after data is collected and/or made available. It would be really interesting to build in some questions around that topic….

This is a case of “not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” The self-monitoring movement is jut another manifestation of our profound self-absorption. When you measure something, presumably you have to react to it. Is the hope that this constant self-monitoring will change our behavior? My guess is that it will simply generate revenue and speaking opportunities for its aficionados and compost, but have little impact on public health. Just look at how decades of focus on diets and weight have fared. In fact, it feels to me that this fixation on blow-by-blow narrative of our “health” is quite the opposite of what real health looks like. Oh, well, call me a luddite!

Marya, you are no Luddite.

But you might be interested in Jay Parkinson’s latest post:

Why health and social media don’t mix

http://blog.jayparkinsonmd.com/post/19238089868/why-health-and-social-media-dont-mix

And for that matter his previous post:

Why I didn’t go to SXSW

http://blog.jayparkinsonmd.com/post/19207318114/why-i-didnt-go-to-sxsw

I’ve been talking with a couple of offline friends about QS this week and they both said, separately: yes, I know I should probably keep a food diary and try to figure out if there is a trigger for these migraines, but I just don’t have time.

I guess what I’m hoping is that the alpha geeks of QS figure out how to make such a thing painless, so my friends can finally track their data and start feeling better, faster.

Hi Folks. Due to my own dreadful diagnosis (RSD), I have become a pioneer of self (pain) tracking. Over the last 3 years I have grown to learn that the act of tracking, alone, is therapeutic to most. Now, this is in the realm of chronic pain, and often the kind that is mysterious like fibro and RSD, not general health tracking. But every week I get emails from users of My Pain Diary who have had life-altering changes thanks to the data they have collected and the ease at which they can communicate that data to their doctors. Does the data interface with the doctors’ EHR systems? Nope. It doesn’t need to. But the app is easy to use, so people use it. And the result is instead of the doctor guessing at a patients well-being since the last visit, they have a report that gives as much detail as they want. A simple thing, really. But in practice, it has saved lives.

There’s no doubt that a lot of users will track for a week or so, then never again. But I chalk this up to the ‘treadmill effect’. People know they should, but for whatever reason, they don’t.

I see a lot of talk about ‘big data’, and developing tech to tie together all of this data with existing legacy systems and personal HCRs. But that’s just not going to happen…. ever. By the time anyone figures it out, we won’t need it anymore.

So let the innovators flourish — whether or not it’s in the comfort zone of the establishment — and we will find a better way.

I had a few motivations for writing this post:

1) I wanted to understand my own (somewhat puzzled, somewhat inspired) reaction to Wolfram’s post.

2) I want to gather feedback on our survey questions and confirm that it would be useful to measure the self-tracking phenomenon.

3) I thought it might be interesting to introduce my Quantified Self friends to my e-patient movement friends and see what happened.

I am learning a ton from this conversation and I think there are many people who haven’t commented who are also learning along with us. I already regret my flip “OCD” label and hope that everyone knows that I want to create a conversation space that is welcoming.

Let’s not forget that experimentation is at the heart of science. And just because something hasn’t worked yet doesn’t mean it won’t work in the future. As I like to say, the tools are in place and the culture is shifting to expect that people have access to information and each other. Who’s to say where the next innovation is coming from? Maybe it is self-tracking made easy.

So, while I remain on the outside looking in, I’m listening with big ears, watching with wide eyes, and thinking with a mind that is cracking open a little further thanks to all of you.

Let’s keep this thread going: Who’s got more examples to share? Who’s got a question they’d like added to a national survey? What condition would you like to attack with the kinds of tools that people like Ian Eslick are describing? See:

http://ianeslick.com/what-can-we-learn-from-our-e-mail-logs#more

Hello again Susannah

I’m wondering if you caught The Atlantic’s piece this week by Kanyi Maqubela called “The Reason Silicon Valley Hasn’t Built a Good Health App”: http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/03/the-reason-silicon-valley-hasnt-built-a-good-health-app/254229/#.T19IZbn9JBx.twitter

…in which he claims: “Innovators make products for people just like them. And that’s a problem. Anecdotal evidence suggests the overlap between those who shop at farmer’s markets, wear Lululemon Athletica, frequent yoga studios, and bike to work and those early adopters of Fitbit, Runkeeper, and Jawbone UP is very high. The quantified self, as currently defined, may be about signalling health consciousness among an already highly health conscious population, rather than changing behavior.

“But the demographics of an audience of Lululemon wearers, yoga-practitioners, and vegans is a very different market segment than the obese, the chronically ill, and those with limited access to health education resources.”

A fascinating read. What do you make of it?

And speaking of sweeping generalizations that are sure to get the QS types howling that they do NOT wear LuluLemon, so there! – I too already regret referring here previously to Quantified Selfers with sweeping and essentially unfounded generalizations like OCD or narcissism or navel-gazing. Perhaps I should have instead borrowed Dr. Zilberberg’s premise: “… the self-monitoring movement is jut another manifestation of our profound self-absorption” – which is actually a bit closer to my (non-professional) personal opinion.

I did see that Atlantic piece and was disappointed by the Lululemon gibe b/c it was a distraction from his points about the whiteness, maleness, youth, etc. of health entrepreneurs.

If we’re going to discuss diversity, let’s not make sweeping generalizations about any group. Let’s have a respectful, data-driven, evidence-based-if-possible conversation about what’s possible in health.

I was part of a conversation like that a couple of weeks ago, and I wrote about it here:

http://www.pewinternet.org/Commentary/2012/February/Health-Technology-Communities-of-Color.aspx

There is a lot of opportunity – and a lot of need. Kanyi Maqubela is exactly right about that.

Thanks Susannah for hosting and promoting the discussion.

In Europe we are exploring the same issues using some of your questions

http://www.ictconsequences.net/2012/02/10/citizens-and-ict-for-health-in-14-eu-countries-results-from-an-online-panel-survey/

Hopefully soon it would be possible to compare USA vs. Europe to identify patterns.

However I wonder why nobody has mentioned some “negative” aspects of self-traking following Ivan Illich The medicalization of life

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1154458/

are we also moving to the medicalization of the Internet daily life?

or other issues as surveillance, privacy…

http://www.ictconsequences.net/2011/09/12/health-related-information-as-personal-data-in-europe-results-from-a-representative-survey-in-eu27/

At least in Europe these are also hot topics.

Like Dave, I am fascinated by the self-tracking movement but challenged by the data collection problem – it is extremely hard to change a habit with no immediate reward in order to capture information that may or may not help me understand or change other habits. I’m extremely impressed by the work of the pioneers who are exploring the many permutations of what, how, and why because they are starting to map out a landscape of means and rewards that will eventually find root in more mainstream activity.

Anyone who has been a competitive athlete in the past decade knows that self-tracking of performance is becoming central to the endeavor. For years bicycle racers have known that an elevated heart rate on waking means you are on the edge of overtraining and that you need more rest. Today, those who can afford it, have commercial strain gauges built into their equipment which reports the exact power you are putting out. The reason? To get maximal response from interval training, you have to reach a certain power output each time or you lose most of the training value.

Here it is the competitive spirit that drives the move to tracking. When you reach your peak potential in cycling, the difference between winning and losing often comes down to walking a knife-edge between maximal adaptation and burnout; and this means knowing exactly how your body is responding. This trend is spreading to more and more sports.

Wellness is another area where there is a strong motivation. I used to be exhausted all the time. I purchased a Zeo because I was curious if I could improve the quality of my sleep. The discovery tools didn’t help me much, but I did discover after a few weeks that I was averaging 1-2 hours less than I thought — no wonder I was so tired all the time! The act of measurement itself became a therapy and helped me make the behavior change to improve my sleep without any other changes or investments. I look forward to the day I can do this without putting on a headband (that technology exists!)

The early adopters may be hard to relate to, but I think the concerns about narcissism or obsession are overblown. Almost by definition the pioneers who are doing this are interested less in the practical, but by the act of collecting data itself – it is a fun hobby, not evidence of a psychological problem. It will take entrepreneurs, skeptics and loads of real-world experimentation to figure out the when and how of using what these pioneers have discovered to address specific real-world problems and populations or to find new modes of constructive entertainment. Yes, the next few years will be full of clueless endeavors and dead-ends but that’s the process. When the dust settles, I think we will find that the act of collecting data will no longer be front-and-center, but a relatively lightweight means to an end. We won’t even call it quantified self or self-tracking – it will be like using Quicken or Mint.com to make sure we don’t bounce checks.

> The act of measurement itself became a therapy

> and helped me make the behavior change to improve my sleep

That’s really insightful, Ian – I myself have had the same effect with both the Fitbit and the Zeo, but I hadn’t articulated it.

> the next few years will be full of clueless endeavors

> and dead-ends but that’s the process.

Yes, yes, yes. This is an essential part of wide-open, wildfire, uncontrolled innovation: “Let a thousand seedlings sprout.” The vast majority may not mature, but the whole point is that today we no longer have or need centralized control. I well remember the early days of the Web, when so many people said it was stupid because there WERE a lot of stupid or boring pages … the naysayers were people who didn’t notice what was happening new, for the first time, and where that might lead.

So it is, I suspect, with self-tracking.

p.s. Thanks for the tidbit on bike racers who wake to an elevated heart rate. What are the chances one’s physician could give us that info?

One thing I didn’t get into on the measurement-as-therapy is the use of data as a proxy; when I wake up and see a 90 on my Zeo score, I feel a real sense of accomplishment because it’s an external validation that I’ve met a goal. Interestingly the inverse doesn’t happen to me – I don’t feel bad when I fail to make it – perhaps because it is such a common occurance!

See the company Rescuetime to acquire passive measures of activity similar to those accumulated by Wolfram – I have two years of second-to-second data on what application, document and website I’ve used. All I had to do was install an application. I’ve been considering publishing some of my productivity data online (% of time spent in useful applications) to provide some social feedback on how productive I’m being getting my PhD done. (I’m sharing it with my wife as an experiment:) Kolya Kirienko has been pitching an experience he had on HealthMonth where his failure to adhere (caused by a flare-up) prompted a surge of social support from his peer group on the site which dramatically improved his experience. I believe that social gaming, the increasing availability of personal data, and the opening up of the healthcare environment (patient reports are going in, my medical data is finally starting to come back out) opens up a world of possibility.

The cautionary tales and warnings of overreach are important, however. We need to skeptics because it’s far too easy for these new technologies to deployed in ways that invite misuse over time. Should a company be able to monitor my Rescuetime data and all e-mails submitted on my work computer? Are my self-reported measures of mood going to be made available to my insurance company or influence a ‘health credit score’?

I think the heart rate phenomenon is well known by those with athletic or training backgrounds but I would be surprised if it’s well known outside those circles. For example, if someone is getting CFS symptoms, but is not getting enough sleep (i.e. the average American) but regularly takes spinning classes, then I would suspect overexertion and recommend measuring morning heart rate over time to identify a well-rested baseline so they can detect oncoming exhaustion (e.g. my waking average HR was normally 40-50 bpm but when overtraining it would be as high as 60 or 70 so it’s a pretty clear signal).

Less well known is that peak-to-peak variation in heart rate can predict stress levels. This is a more complicated phenomenon (http://psychology.uchicago.edu/people/faculty/cacioppo/jtcreprints/bc04.pdf) but fascinating. Since we tend to habituate to a given level of stress, external feedback on changes in stress level that can be coupled with a stress-reduction intervention such as meditation, exercise, or a stiff drink? would be really useful to moderating chronic stress. We just need cheaper, less intrusive ways of getting EEG patterns.

PS – Speaking of which, if some readers feel that detailed tracking of our lives is, well, unusual – check out this community of “brain hackers” – self-tracking is just the tip of a immense iceberg. Measurement, augmentation and tinkering with our biology and psychology, for better and worse, is going to touch every aspect of our lives in the coming years. http://engineuring.wordpress.com/2010/04/25/consciousness-in-mixed-systems-merging-artificial-and-biological-minds-via-brain-machine-interface/

Hi Susannah and crew,

Thanks to all for this great discussion. I’d like to take the position that self-tracking is already extremely widespread – it just flies under the radar, esp as I think a lot of it is of the paper and pencil variety, as noted by Elizabeth.

Most people self track their weight – either by a scale, or by how their clothes fit. I would guess that the vast majority of women track their menstrual cycle – either to get pregnant (fertility tracking), to not get pregnant, or to track the absence of their cycle (menopause). Alcoholics Anonymous and Weight Watchers are all about self-tracking. Pedometers have been popular for more than a decade. Among the more than 10,000 people in the National Weight Control Registry (those who have successfully lost an average of more than 60 pounds, and have kept off the weight for more than 5 years, http://www.nwcr.ws/) one of the common characteristics of these successful folks is self tracking (body weight, daily food intake, and calories and/or fat grams).

I’m a physiologist who swoons over the data from gadgets that monitor our electrical, chemical, and mechanical signals. But when I give talks on self-tracking, I take care to point out that tracking is not just about the data. It’s about capturing a narrative or journey, which is the point that Katie McCurdy makes so wonderfully in her post. And it’s about the sense of self-empowerment (whether real or perceived) that tracking provides.

To Gary Wolf’s point (who I often quote!), looking forward, what we’re going to see is that the ultimate self-tracking device will be the ubiquitous smartphone. But it’s not about cool apps – at least not yet.

As your great Pew data show, smart phone owners use their phones for lots of things – esp to snap photos. (http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Cell-Phones/Key-Findings.aspx) There’s a great video from YouTube (a huge self-tracking community) of a lovely woman who chronicled her weight loss journey (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ws-yl37lWE). She’s a self tracker. But she doesn’t use fancy gadgets or apps. She uses a scale, how her clothes fit, and photos of herself that she takes with her mobile phone. Through tracking she shares her journey to take control of her body. And she reminds us that it’s not about technology. So I think lots and lots of folks (male and female) are tracking, but we just aren’t capturing them – yet.

Hi all,

Awesome conversation! I’m a little late to the discussion (technology fail!), but if anyone’s still listening, here are some thoughts from a current patient. Sorry this post is a little epic.

FIrst, I wanted to address the oft-repeated quote in this thread that self-tracking or data gathering is “a manifestation of our profound self-absorption.” Sure, self-tracking is all about ‘me,’ (hence the word ‘self’) but there seems to be an undertone that people are motivated to track their data by vanity or narcissism. This may be true for some people, but there are others who are motivated by true medical necessity – diabetics needing to track their blood sugar, or people suffering from unexplained medical mysteries. I fall into the second group.

For the past 20 years I have had Myasthenia Gravis, an autoimmune disease that causes weakness. For the past 14 years I have been taking Prednisone, a corticosteriod, to suppress my immune system. Unfortunately prednisone causes a host of side effects. For the past 5 years I have been experiencing gastrointestinal problems (debilitating at times) and increased weakness. I have been to neurologists, a number of gastroenterologists, acupuncturists, a couple primary care doctors, and NONE of these folks were able to really explain what was happening to me or give me concrete advice for improving my condition.

As I was getting ready to see a new doctor, I realized that the best way to tell my story would be to create a medical ‘life story’ timeline that reflected:

– The course of my autoimmune disease

– Severity of my gastrointestinal problems

– Key moments in time when I started and stopped certain medications or took antibiotics

– Any significant dietary changes

I sketched out the two timelines (autoimmune and gastro) separately, and then created them electronically using Adobe Illustrator. (I’m an interaction designer by day, so fortunately I had the skills/know-how to create a legible artifact.)

An important note – I did create my timeline from memory. I clearly remember, almost to the day, when my severe flare-ups happened. Like others, I have had a very hard time motivating myself to track my data daily and I don’t think I can bring myself to actively do it; until passive data collection exists for my specific disorders (or until I come up with a mechanism to force myself to track how I feel each day) I might have to just work from memory.

After I completed the timeline I printed it and took it to my doctor visit.

I can’t say the doctor was overjoyed at first to see a patient-created chart, but he listened intently as I used it as a storytelling prop. It definitely helped me quickly and coherently communicate what’s been going on with me, and when I asked him if he found it useful, he said it was helpful to get him up to speed on my story.

Last month I attended a workshop at the CSCW conference (with Joe McCarthy, also on this thread), and had the opportunity to show a print-out of the timeline to another doctor. He said that most doctors inwardly groan when a patient comes in with excel data, charts, graphs, and the like – mainly for reasons listed by other commenters, e.g. patient data may not be totally accurate, and often there’s a high learning curve for understanding this type of documentation. But after I gave him a few seconds with the timeline, he became very excited and animated and said this was something he could understand immediately. The main lesson I’ve taken from that experience is that there is a definite need for a patient tool that would allow them to create legible, clear, communicative visualizations (perhaps even exploratory data visualizations) so that they can:

1) Better understand what is happening to them and how their behaviors impact how they feel

2) Better communicate with health care practitioners

Let’s face it, even if a doctor is wary of a patient-generated timeline, if that artifact makes the storytelling process easier for the patient & more coherent for the doctor, it adds a lot of value even if the doctor doesn’t want to take time to carefully analyze it.

So what are the outcomes from this experience?

My new doctor has helped me resolve my most serious stomach issues, and it has been awesome to have some relief after years of discomfort and anxiety.

I can say that visualizing my history has helped change my behavior. Seeing the high number of times I took antibiotics in a short time period, and learning from my doctor that such repeated use of antibiotics causes overgrowth of yeast and bad bacteria, has helped me escape the antibiotic trap. Whereas a year ago I was calling my doctor for antibiotics every few months (they helped, but only for a month or so), now I work on adhering more carefully to a no-carb diet.

My goal is to keep pursuing this idea and work toward creating a tool for patients to use to at least assemble their own health timeline, and perhaps even track their data more regularly. I am holding interviews with patients, patient caregivers (or parents), and people who are involved in self-tracking; if you are interested in donating about 30 minutes of your time, email me at kathryn.mccurdy@gmail.com.

Here are links to the 2 blog posts (with visuals) I wrote about my experience w/this timeline:

http://sensical.wordpress.com/2011/11/16/how-visualizing-health-problems-could-help-solve-medical-mysteries/

http://sensical.wordpress.com/2012/01/03/medical-history-timeline-a-tool-for-doctor-visit-storytelling/

Finally, if anyone is going to be attending the Healthcare Experience Design conference in Boston on 3/26, let me know! I would love to meet you!

The party is never over on e-patients.net – some of our best discussions have lasted days and even weeks.

Thanks so much for adding your voice (and for making me even more envious of people who are attending HxD: http://www.healthcareexperiencedesign.com/)

Hi Katie,

Great perspective on self-tracking. Would love to chat at HxD. I’ll be there speaking on Monday and running a workshop on Tuesday. Would love help get you more data and folks to talk with.

Cheers!

Dustin

I’m late to the party, but I’d like to offer a comment or two about QS. I’m a member of the QS group in Portland, OR, and I maintain a QS page on Google+: +Quantified Self PDX.

I followed QS distantly when I lived in the SF Bay Area and worked for a non-profit cancer control organization. But I retired two years ago at 65, and moved to Portland. When I re-enrolled in Kaiser Permanente as a Medicare patient I learned that I had a high blood pressure reading, my cholesterol was in the “high” range, and I had symptoms (thanks to data from my wife) of sleep apnea. Yikes, retired and going downhill fast!

Although I had been a health educator my whole career I realized I had not practiced rigorously what everybody (including my employer) was preaching: eat a careful diet and get a lot of exercise. Coincidentally I learned that the Washington County Parks and Recreation Dist where I live has an amazing system of fitness and sports facilities available to county residents at low cost.

One center, the Elsie Stuhr Center, is specifically for people over 55. This month I celebrated one year of “working out” at their exercise center two or three times per week. (I’d like to share more about this operation some time because I think centers all across the country are desperately needed for us aging baby boomers if we aren’t to bankrupt our health care system.)

To succeed at my exercise and diet regime I found it essential to start consistently measuring my exercise and diet. The exercise center encouraged constant recording of aerobic exercise duration and intensity and strength training weights and repetitions. Those records enabled precise track of progress rather than haphazard exercise sessions.

I had started using iPhone pedometer apps even before I retired to track walks. For my new routine I needed something to record both exercise and diet . I finally settled on the Livestrong.com “MyPlate” tracker because it enables daily recording of weight, meal calories, exercise and other daily physical activity, and water consumption. I have used it consistently for about eight months and found recording helpful in several ways:

1) Keeping a reasonably accurate record of stuff you can’t keep in your head;

2) Identifying the eating and exercise imbalance that put a couple of pounds a year on me for 20 years; and

3) Having a commitment to record things creates accountability for behavior because, if you are tempted to have a big dessert, for instance, you’re aware you are going to have to punch it in rather than ignore it.

Also, Livestrong.com is a full website to which you upload your data for better long-term graphing. And, Livestrong is in my opinion a fairly careful and accurate source of nutrition and exercise information. I know of no website of “medical” or health information that truly addresses detailed nutrition and exercise issues for people actively managing their own fitness program.

As a result of my lifestyle change and self-monitoring I have brought my BMI down to 26, lost 17 pounds, brought my cholesterol down to high-normal and stopped taking statins, gained visible muscle, and increased strength, energy and stamina. I really didn’t expect that much.

In the midst of all this I learned that a QS group had started in Portland. I have shared my self-monitoring activities with other QS members and they with me. QS is a pretty eclectic set of practices and ideas. People have a whole range of reasons for doing self-monitoring. Some are fascinated with the gizmos and with data (e.g., Wolfram, who’s in a space I don’t comprehend). Others are just looking for self-awareness.

My interest is strictly in health, and I foresee a whole set of waves of change as suggested in some of the comments above. There is a long learning curve and shake-out period ahead, but I’m convinced some of it will result in useful tools for being engaged and knowledgeable about our health. Given what’s going on in the US health care system (if you can call it that) we’re all going to need to have tools and knowledge at our fingertips for being much more responsible — and empowered — for the direction of our lives.

One final thought. As a person who has been applying, finally, the health canon of our times — eat healthy and exercise — I have experienced a real disconnect between the general recommendations of health organizations and the task of putting those things into detailed personal practice. I have found it more productive to consult sources focused on “fitness” and sports than medical sources.

The health system is built to go into action with a whole armamentarium when you’ve finally been diagnosed with an illness, but others are way ahead in helping learn healthy lifestyles. My whole career we called that “prevention.” It’s no wonder it has been difficult to get prevention to go mainstream; the dominant health care institutions are really deficient.

> As a person who has been applying, finally, the health canon of our times —

> eat healthy and exercise — I have experienced a real disconnect

> between the general recommendations of health organizations and

> the task of putting those things into detailed personal practice.

> I have found it more productive to consult sources focused on

> “fitness” and sports than medical sources.

Fascinating, and a great observation!

Hypothesis: the fitness & sports audiences are already engaged in pursuing health – you might say they’re already “activated.”

What can you share about what you were seeking (and how you searched for it) when you failed to find it on medical sites? I know some medical sites (I can’t rattle them off) do have fitness resources; are you saying their info isn’t robust enough?

Hi, Dave. Your question made me think again about my journey over the past year and especially about some of the frustrations I encountered along the way. Perhaps suggesting medical sites didn’t have the information is a poor way to put it.

Maybe a more accurate statement is that my needs with respect to information and support changed as I became more deeply involved in fitness, and I sought multiple sources online. Some provided a specific bit of information and others had an array of things that I found helpful. I sure didn’t find one source that did it all.

When I started my process I was looking for information about lowering salt, fat and carbohydrate intake. I soon discovered that there are few grocery products that aren’t problematic in one or more areas . Restaurants are nearly hopeless unless all you eat is salads with dressing on the side.

It was months before I found a fitness article that told the truth: to eat healthy you need to abandon nearly all commercially processed food products, start with the raw materials, and cook for yourself. To use a Pacific Northwest analogy, getting good nutrition is like a salmon swimming upstream. We live immersed in a commercial food culture that takes little or no responsibility for the health impact of their products. Changing that situation is like turning around smoking. It’s changing some, but there’s a long way to go.

When you start producing your own foods you then need a lot of nitty-gritty information about nearly all food. It’s like learning to cook all over again. You need more than the usual list of healthier vegetables, meats and grains; you need variety and alternatives.

Similarly, my exercise knowledge needs evolved. I think there are different levels of commitment to exercise as you learn what’s necessary to achieve certain things and you learn more about what’s possible for your body to do. I suspect that’s true for other significant habit changes. Before I joined the senior citizens gym I had been walking 45 to 60 minutes/day. But here, near Portland, four or five months of the year the weather can discourage outdoor exercise. So when I started I just figured I’d use the indoor treadmill and keep some cardio going.

I had another motivation: my retirement was also a confrontation with my age and the diminishing amount of active life I could look forward to. Frankly, I got depressed. Any exercise, I figured, might in some way stave of the decrepitude I imagined. But my expectations were limited.

But something interesting happened. The exercise regimen, to my surprise, included strength training. The center had a set of machines for working all major muscle groups. After a couple of months I began to feel and see muscle building. Frankly, I didn’t expect that. My wife and I both experienced increased endurance. We were able to do chores like house cleaning and gardening for longer periods without being worn out.

Suddenly a light went on. My body was able to recover more strength and better appearance than I thought. I was sticking with it and getting more than I expected. With that epiphany my level of commitment jumped to a new level. I realized that I could change the remainder of my life by embracing a determined exercise and nutrition program. In my opinion success in many of the life changes we expect of people to improve health (smoking, drinking, obesity) may require a transformative sense of commitment and of what’s possible for them.

Suddenly I wanted a great deal more information about nutrition, exercise, and their synergistic effects. The senior editor of Livestrong.com wrote an editorial a few weeks ago in which he stated that once people catch fire about fitness they suddenly want to know everything. They become sponges about nutrition, exercise, and how the body works. That can be a problem for information editors because it’s not easy to provide substantiation for some of these things. Eager new fitness buffs are also picking up information from their friends, a lot of which is opinion or bogus.

I fit that situation pretty well. I wanted to know about when to take protein supplement, before or after a workout or both? Is whey or soy protein better? How does shedding fat while adding muscle work? How much rest is needed after a workout? Is one workout enough or should I cross-train? How much water? And on and on. That’s when I found most medical information lacking. On the other hand, fitness information talks about all of those things…with one caveat: a lot of things that people do isn’t backed up by “evidence-based medicine.” You’ve got to use critical filters.

Then I found another thing that the “fitness” practice gave me that I needed: an identity. I began to identify with the segment of people doggedly pursuing specific goals that take a lot of effort. Rather than an old guy out for his ritual walk, I was looking for measurable improvement.

The fitness movement is embedded, for better or worse, in a big commercial environment. Shoes, clothes, equipment, supplements, and DVD workout programs are the lifeblood of the fitness world. It’s full of over-the-top motivational messages and images of impossibly sculpted young men and women in spandex. It’s no doubt pretty effective for marketing, and I can’t say whether or not all that has a positive impact on people in general, but it certainly takes fitness out of the “get well” sense and into the optimization realm.

Fitness implies a whole continuum of healthyness, not just a dichotomy of sick vs well. I’ve toyed with the idea of going to my Kaiser doctor and saying, “Doc, I’d like you to help me get well-er.” This differs from the standard model of care delivery, so I imagine he’d say, “Don’t waste my time.”

I mention this because I think one of the things overlooked in the standard medical approach to behavior change is the role of human drivers such as vanity, pride, accomplishment and confidence. When I entered public health 40 years ago I thought people would change for the better because it was rational. Just tell people the risks of smoking like cancer and heart disease, and they’ll quit, right?. Boy, was I in for a surprise.

These days I don’t think worrying about the vague risk of cancer is going to motivate obese people to work their asses off for a couple of years to drop 40 pounds, but they might do it if they think they’ll also look decent in a bathing suit again. There’s a difference between avoiding disease and working toward optimal health. I think “fitness” embodies the latter.

That brings me back to the QS topic again. Fitness freaks are possibly the original quantified-self trackers. Tracking runs, bike rides and pushups has been around for a long time. Feedback from numerical measures of improvement what people say and how you look and what you see in the mirror is all indispensible for change.

Thanks for the opportunity to ramble on and explore my experience. I hope it’s useful to some.

David, thank you, on behalf of myself as a researcher trying to better understand these trends and as a person who is also pursuing health beyond the dichotomy of sick/well. And I’ll be so bold as to speak for anyone else who reads it: Wow, this is inspiring!

Have you ever heard Esther Dyson talk about creating a new market for health? I found these two videos that begin to explain it:

Three markets for health:

http://www.health2con.com/tv/esther-dyson-health-not-healthcare/

Health 3.0:

http://www.health2con.com/tv/closing-address-by-esther-dyson/

Thanks, Susannah, for the generous remarks. By the way, I’ve been an admirer of your work for years.

I’ve haven’t done much blogging about my fitness journey (most people call fitness a “journey.” It’s sure not a one-shot effort!) But if it’s helpful to anyone I think I’ll start putting more down.

For instance, just this morning I visited my doctor to check something. I’d lost quite a bit of belly fat in recent months, but I noticed that there were a couple of bulges, uh, lower down. (Too much information?) Sure enough, I’ve got a double inguinal hernia.

Weight lifting has contributed to the situation. So now what do I do? Well, after surgery I’ll have to explore carefully what I can do to get back on my path to staying healthy.

But that’s a part of a commitment to fitness. Especially as you get older some real obstacles can get in the way. It feels like Catch-22 sometimes. You want to get fit, but the rickety parts you’ve acquired over the years almost defeat you.

The key to fitness, however, is not getting defeated, and there’s plenty of motivational posters out there that say that.

I don’t know what’s next, but I’ll make whatever it is public.

Also thanks for the Esther Dyson links. She’s spot-on about health 3.0. The exciting thing for us on the periphery of the multi-billion-dollar health industries is to aggressively push ahead to make change through what we do. That’s where change comes from, right?

I am with Dave, way up at the top, that to be really useful self-tracking needs to be a by-product of daily life.

That being said, I was an obsessive self-tracker when I first developed asthma, in my 30’s, as a part of an effort to understand my disease and what it was doing to my life. I tracked my peak flows 3 times a day, graphed them using Excel, overlaid the times I was on Prednisone and antibiotics, and could present a chart to my doctors to show where I was in any given asthmatic bout. I learned a lot about my disease that way (as well as a lot about my doctors from the way they reacted to my data and my knowledge).

What I couldn’t do, however, was figure out from the data why sometimes I would get to a point in the cycle and recover on my own and sometimes I would get very ill. I just couldn’t track enough data–ambient temperatures, pollen levels, my stress levels and immune system health.

The promise of today’s environment comes, I think, from the combination of the capacity for collecting data through ambient sensing devices, combined with the potential for mega-analysis of many disparate and seemingly unconnected pieces of data to shed life on health and disease and the relationship between the two.

Thanks, Jan!

If you have time to read another post and lend your expertise, I’m seeking input on the upcoming Pew Internet health survey, which will again include questions about self-tracking. Here’s the post:

Unpacking Self-tracking

http://susannahfox.com/2012/06/07/unpacking-self-tracking/

There’s a new thread happening over on Katie’s post now if anyone wants to join:

http://pmedicine.org/epatients/archives/2012/03/visualize-this-an-e-patients-medical-life-history.html