Here’s another true e-patient story from one of our team.

Cheryl Greene is third from the left in the banner at top of this blog. She’s a long-time friend of our founder “Doc Tom” Ferguson, a board member of the Society for Participatory Medicine, executive producer of DrGreene.com (AMA: “the pioneer physician web site on the Internet”), and oh yeah, wife of Alan Greene MD. And a heck of an e-patient, starting ten years before I ever had a CAT scan.

This stuff matters. These are stories of real lives facing lethal threats. As you read this, try to immerse yourself in the experience of someone who tried for 15 years to get pregnant, gave birth, faced a magnificent and much-longed-for future, and was suddenly told she had months to live.

This is real. And now, like many e-patients, she’s paying it forward.

Cheryl has just passed a phenomenal milestone. Here’s her story, cross-posted from DrGreene.com last month.

___________

This September8, I went to my doctor for my annual physical. I’m very diligent about getting my regular checkup because I have a history…

On March 22, 1996 I was diagnosed with stage three inflammatory breast cancer and this doctor, my gynecologist, has been with me the entire time – she was my doctor even before the diagnosis, back when I was struggling with infertility and trying to have a baby. She was the very person who diagnosed the breast cancer. She is a phenomenal physician and a very trusted advisor, and now she is a friend.

And this year, my doctor, my friend, looked at my charts and my paperwork, then turned to me and said some of the most beautiful words I’ve ever heard: “We can now call you cured.”

My breast cancer is gone. Done. Over. Nonexistent. We don’t have to use words like “remission” or “no evidence of disease” or talk about a “probability of recurrence.” This cancer that almost took me away from my children and my husband is truly cured. And just as I remember that day in 1996 when this same woman told me I had a deadly form of breast cancer, I will forever remember the day she told me I was cured.

I want to tell my story publicly for a number of reasons.

- First, my diagnosis of breast cancer was one of the reasons Dr. Greene and I changed our lifestyles and dedicated ourselves to sharing health information via DrGreene.com.

- Second, my experience as a cancer patient taught me important lessons about how patients need to participate in their own healthcare.

- And third, because I want to spread the word that people can live through a fatal diagnosis, even when the odds seem overwhelming.

My doctor told me that when she talks to other women with breast cancer, she calls me her poster child. What I had was supposed to be fatal, and if I can beat that cancer, others can, too.

Getting the Diagnosis: All You Hear is “Cancer”

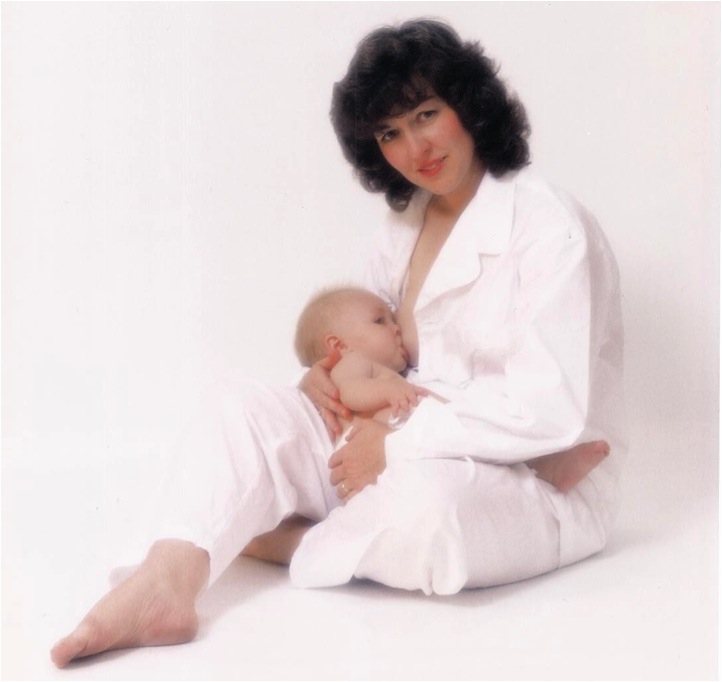

I tried for 15 years to get pregnant, and when I was told that we should prepare to welcome a baby boy, I was determined to do everything right. I was prepared for the challenges of breastfeeding, but it turns out that my son and I were the perfect nursing pair. He did a great job of latching on and drinking, and I did a great job of producing “liquid gold.”

Then I developed a breast infection. Many nursing women have them – painful, but no big deal. I felt a lump that seemed like a clogged milk duct. But when the infection went away, the lump stayed, so I went back to the doctor.

The doctor came in and examined me. My son, then 9 months, was on my lap, and she laid one hand on my breast. Then she said abruptly, “Ok, you can get up now,” and started ordering tests. Later she told me she knew what the lump was as soon as she touched me.

The doctor came in and examined me. My son, then 9 months, was on my lap, and she laid one hand on my breast. Then she said abruptly, “Ok, you can get up now,” and started ordering tests. Later she told me she knew what the lump was as soon as she touched me.

I was very lucky. From the time I had the breast infection to the time I had the definitive diagnosis was six weeks. Breast cancers in breastfeeding women are rarely diagnosed this quickly because the breasts are so lumpy when you’re nursing.

But when the surgeon came in and told me I had breast cancer and I had to stop nursing, all I heard was, “YOU HAVE TO STOP NURSING.” I didn’t listen to the details about how serious this cancer was.

When you’re diagnosed with something that’s really devastating, there’s only so much you can hear. For me it was that I couldn’t breastfeed any more. All I could think of was, “How will I feed my baby?”

A couple of months later, I sat in my oncologist’s office and received more bad news. He was talking about treatment and told me I had only months to live. But before he told me my prognosis, he told me, “YOU HAVE TO HAVE REALLY STRONG CHEMOTHERAPY AND YOU ARE GOING TO LOSE YOUR HAIR.” That’s all I heard.

If you are close to someone who has just received very tough news, she may not realize what the actual news is yet. One of the best gifts you can give this person, besides just being there, is to accompany her to the doctors’ offices and write down everything the doctors and nurses communicate. Then give the patient some time to digest the big news and schedule a quiet time to go over the other details. This is a very vital service a caregiver can provide for a patient in need.

Getting Treatment: How I Became an e-Patient

When I started treatment, my goal was to make sure the medical staff thought of me as the perfect patient. I was going to do exactly what they said to do and follow all the rules – and I was going to be happy about it.

The first six or seven months, that was the way I operated. I went through chemotherapy and a lumpectomy. At one point the team decided I should have a port implanted in my chest so the drugs could be administered without needles in the arm.

I preferred to undergo the surgery under conscious sedation to implant the port because I didn’t seem to recover as quickly when I was fully sedated for a surgery. The anesthesiologist was someone I knew, and we were talking before the surgery. Then they put the drape up between my face and the surgical field so I couldn’t see where they would be cutting. I was still very aware of what was going on even though I couldn’t see it or (theoretically) feel the surgery. I heard the anesthesiologist say, “Ok now – no whining.” I steeled myself, “I’m going to be good and I’m going to be strong and I’m not going to whine.”

But the surgery was not what I expected at all. During one part of the procedure, when the surgeon was using what seemed like a hammer and chisel to pound the port in place inside my chest, I didn’t think I could take it. I was trying so hard to be strong, but it was awful and I felt like passing out. But I didn’t whine.

After the procedure, I told the anesthesiologist how hard it had been. And his face contorted and turned white. “Why didn’t you tell me?” he said, upset. “It’s my job to make sure you’re comfortable!”

“But you said, no whining,” I replied.

I was shocked when he said, “But I was talking to one of the nurses.”

Light bulbs went off. Right then I realized that I was the only one in the room who had information about how I was feeling, and it was my job to communicate that. I needed to stop being a compliant, non-complaining patient. I needed to speak up and share the information about what was going on inside my body with the rest of the people who were working with me to try to fix it.

In the course of the next six to seven months, I completely changed how I interacted. I learned how to give myself a shot I had to take daily so I didn’t have to wait on a nurse or get an appointment. I worked with my doctor on a daily plan for my medication, which needed to be adjusted regularly when we were trying to figure out what would work. I had gotten to the place where I knew what I needed. My doctor was reviewing my suggestions, but I was making decisions. I credit that engaged, that empowered, behavior as one of the reasons I was cured.

Enduring the Journey, Finding the Cure

I started off with the strongest Western medicine available, and at the end of my treatment, I was in a very vulnerable position. The cancer was gone, but the first year after treatment has the highest risk of recurrence. And cancer that comes back during this time usually spreads very quickly and is very resistant to more treatment.

I started off with the strongest Western medicine available, and at the end of my treatment, I was in a very vulnerable position. The cancer was gone, but the first year after treatment has the highest risk of recurrence. And cancer that comes back during this time usually spreads very quickly and is very resistant to more treatment.

I decided I wanted to be as involved as I could in attacking this thing. I found about a trial at Stanford that the coordinators were having trouble finding participants that fit the critera. You had to have been diagnosed with stage three or stage four breast cancer, and you had to be done with treatment with no evidence of the disease. The hard truth is that they couldn’t find many eligible patients because there weren’t many of us who were surviving this disease. When I was first diagnosed Alan tried to find people online with my cancer, and he couldn’t find anybody. He just kept finding memorials for people.

So I enrolled in the FGN1 trial at Stanford. I knew I had a 50/50 chance at getting the drug, but either way, I was determined to do it. Either I got the drug, and perhaps got help, or I didn’t and hopefully helped others.

The trial was an 18-month chemotherapy treatment, but I knew right off that I was getting the actual drug and not a placebo because I had to be hospitalized because of the side effects. They adjusted my dose a couple of times because I was so sick with the side effects, and they actually asked me if I wanted to drop out. But I wound up completing the trial because I wanted to help find a treatment that would help more people than the conventional chemo.

After the trial, the doctors told me that of the six women at Stanford who were on the trial, several on the placebo had recurred and one had died. At that time the cancer had not come back in those of us who received the actual drug. I haven’t been able to track down any of the other women in the study, soI don’t have any long-term data. Unfortunately the side effects turned out to be too serious to take the drug to market, but I’m grateful I persevered and got the full treatment.

There’s no doubt that the chemotherapy is one of the major reasons I’m here to tell my story today, but I’m fully convinced that my mindset played just as significant a role. When I was diagnosed, I didn’t absorb their message that I was going to die. I heard what they were saying, but I was convinced that the fatal diagnosis didn’t really apply to me. At the same time, I can remember realizing that I needed to live every moment to the fullest.

______

Humans are capable of two diametrically opposed ideas at the same time. I remember one morning in particular waking up and feeling totally exhausted. I felt tired on the cellular level, and all I wanted to do was just turn over and go back to sleep. But I said to myself, “You may never feel better than you do right now, so get up and get dressed and go play with that baby.” I remember feeling like I didn’t really accept this diagnosis and that I was going to make it, yet coming to the conclusion that I needed to live every moment because they might not come again.

That combination really served me well. And the take home lesson for me was that it is really important to live today and not miss today. I really learned to take advantage of opportunities… to seize the day.

What are you doing today to live this day to the fullest?

Life after Breast Cancer

Although it was just a couple of weeks ago when my doctor looked me in the eye and called me cured of the breast cancer that had almost ended my life, I’ve actually considered myself free from cancer for quite some time. When I was diagnosed, Alan and I took a serious look at our lifestyles and our environment and made significant changes that last through today. We share many of our insights on the benefits of healthy living here on DrGreene.com, and we’ve come to embrace our good health and to enjoy our good days.

I fully believe that some of the healthiest people in the world are those who are living with a chronic disease and managing it well. Those of us who have gone through a life-changing threat to our existence have sought out information about the world we live in, the food we eat, the air we breathe… we want to do anything and everything we can to regain and maintain our health.

People with diabetes who watch what they’re eating and control their disease with diet and exercise are healthier than most disease-free folks who eat junk food and spend their evenings on the couch. People with asthma who avoid second-hand smoke are exposed to fewer toxins. We survivors of diseases just seem to be more aware of what keeps us healthy and what will make us sick because if we don’t pay attention, the repercussions could be very serious.

____________

Some days I’m really angry about what cancer stole from me. I was breastfeeding one day and two months later I’m in full menopause with hot flashes because of the chemotherapy. It was insult to injury because I hoped to have another child at that point. During my treatment I opted to do everything I could to keep my breasts because I fully believed I would nurse again.

But the anger about the cancer doesn’t come close to the happiness about the cure. I was diagnosed with stage three inflammatory breast cancer. The chances that I would survive were very, very small. But survive I did, and, as another cancer patient once said to me, “Today is a great day to be alive.”

Perfect post to read on the morning of the FDA hearings about social media. This paragraph grabbed and held my attention:

“I fully believe that some of the healthiest people in the world are those who are living with a chronic disease and managing it well. Those of us who have gone through a life-changing threat to our existence have sought out information about the world we live in, the food we eat, the air we breathe… we want to do anything and everything we can to regain and maintain our health.”

After reading it I thought, “May we muster the strength, courage, and generosity to share our insights with others.” Clearly, the contributors here are doing so.

Cheryl,

I vividly remember Alan sharing your story at one of our Ix conferences many years ago and it brought everything together. Reading it in your own words is even more powerful. Thanks so much for sharing.

Josh

Cheryl,

I remember too the first time we met, invited by Tom Ferguson, to start working collaboratively on the e-Patients White Paper and realizing that while we started ACOR because of the wrong diagnosis given to my wife and the absurd treatments the &^%$#@ breast surgeon who played G_d wanted to give a woman with Stage 0 breast cancer, you had been through the almost exact opposite, dealing with an instantly life threatening situation. I have never forgotten!

Written down the story is even more powerful than what I remembered. I hope many people will read it.

Cheryl, many congratulations and thank you for sharing this story.