We’ve talked in the past about “d-patients” – doctors who become e-patients themselves. Our own founder Tom Ferguson MD was one. “D-patients” are a special case that proves, once and for all, that being an e-patient has nothing to do with rejecting the medical establishment,  as some have feared. Being a d-patient, or any e-patient, is about being empowered, engaged, and participatory.

as some have feared. Being a d-patient, or any e-patient, is about being empowered, engaged, and participatory.

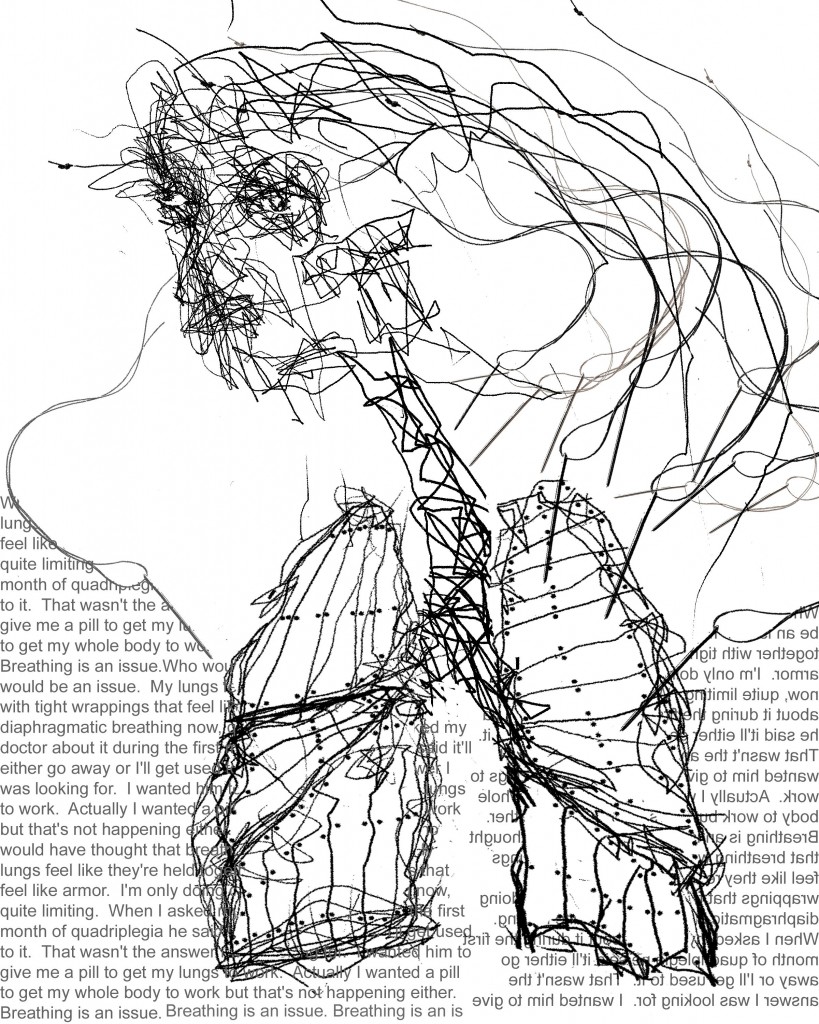

This special guest post is by Alan Pitt MD, a radiologist at a neurological hospital who found himself being a participatory caregiver: his mother, an accomplished artist, became a quadriplegic. At left is a drawing she later did, showing what her breathing felt like when she first came off the ventilator, with her chest walls very weak. This drawing has been accepted into several national exhibits.

The medical story is compelling, but as with all patients, when all is said and done, life goes on. In this thoughtful essay Dr. Pitt asks why we can’t have better e-tools to make it easier for the family to participate in her care.

The Apex of Care

My name is Alan Pitt. I am a successful physician at the Barrow Neurological Institute (BNI), the U.S largest hospital for neurological disease. As a senior radiologist, I have a good idea who are the best doctors and how to get things done at my hospital quickly. Every year we take care of thousands of patients with brain tumors, epilepsy and spinal cord injuries to name a few. There is process to care for these patients referred to as best practice. We hope to optimize their outcome while they are in our care. I am also the son of a quadriplegic, Sheila Pitt. Danny Sands, a friend, thought it might be of general interest if I gave some perspective on her story, and my observations since her accident.

Here is some background on my mother. She has always been a strong, independent person. Growing up she successfully competed in women’s gymnastics. She wanted to go into art, but that was not an acceptable career for a good Jewish girl in the 50’s. Her father suggested she was better suited to be a teacher. After marrying, she pursued a fairly traditional life as a spouse and mother.

After we moved to Arizona in the early seventies she developed a passion for horses. She was an Equestrian. She began riding in her 30’s and continued in the sport for over 35 years reaching a high level of competition.

In her forties she also went back and pursued her dream of becoming an artist. She got her MFA at the University of Arizona. She received tenure in her late forties and was made head of the printmaking department at the University of Arizona. Her work has been shown at national and international shows. She was also asked to advise the undergraduate studies program for the department, managing over 750 undergraduates. She was elected to the Faculty Senate. She is no wall flower.

The day of her accident was a bit bizarre. I was participating in a new building dedication. Most of the neurosurgery department was in attendance. Late Saturday morning, I got a call from my sister. She wanted to tell me mom had an accident. She had fallen from her horse and the paramedics were there. I didn’t think much of it, but was able to reach another friend at the scene who put me through to the paramedics. They were taking her by ambulance the hospital. She was complete from the neck down. I collapsed in front of 50 of my peers.

“Complete” is a term in neurosurgical terminology meaning the patient isn’t moving below a certain level- neck, chest ,waist- and really isn’t supposed to move ever again- they are complete.

There were a series of tests and stabilizing care given in Tucson. Within 8 hours I had her helicoptered to my hospital 100 miles north. By midnight she was in the operating room with one of my close friends and best spine surgeons in the country, Dr. Nick Theodore. I honestly believe my mother’s functional status would not be as high without this prompt intervention.

As a senior physician at the BNI, I was able to guide much of my mother’s course through the ICU, step down and rehabilitation facility. Another friend, Dr Rick Su, prevented her from requiring a tracheostomy by patiently monitoring her respiratory status at a critical time. This procedure involving a breathing tube inserted into her neck, would have meant several months of additional recovery.

When she arrived at the rehab floor, Mom had minimal movement in one shoulder, but could breathe on her own. She began a course of aggressive therapy. Therapists worked on her limited strength and function most days.

Occupational therapy was perhaps one disappointment. We wanted to have Mom trained to use voice recognition on the computer. This would enable her to read and respond to email, in essence, get her closer to reintegration with activities of daily living. We were told they did not have the staff to train her on the computer and would only offer skills for her to type the keys with a pencil. We arranged for a local high school to volunteer. Students would offer computer assistance with the software program in exchange for volunteer hours at the facility with my mother and other patients having similar injuries who asked for help. It would be a win-win. This opportunity was passively refused by the hospital occupational therapy supervisor.

She spent several months there with some gains. She was able to push up her glasses with one arm. However, after a while, she wanted to go back to Tucson. Her husband and friends were there. Phoenix was not her home.

The Base

As a quadriplegic the only place in Tucson meeting her medical requirements and that her insurance would pay for was the county nursing home. This is a clean but rather Spartan facility. The staff was nice but limited, and the physician rarely seen. She was placed in a room with roommate. This woman had been in a chronic vegetative state (most would call it brain dead) for 15 years with no chance of recovery. All Mom could hear was the in and out of the breathing machine. Although she said this was a plus (she didn’t have to be bothered by idle conversation), I know this wore on her.

It felt like a dream to me. She showed tremendous strength. One minute she was a professor in front of students. A horse stumbles and she is unable to move or reach a call button. The person next to her was one in name only. After another month, custom changes to her home were completed. She left the nursing home and remains at home today. She has 2 care providers on any given day.

Whereas I could monitor and optimize my mother’s care at the BNI, in her new surroundings I am largely reduced to a family member. Certainly other care providers make themselves available to me. However, largely her care is reduced to the base – self driven and self monitored with no real “captain” of her ship. She has a multitude of providers – a urologist, a neurologist, a physiatrist. Each deals with individual issues they are comfortable handling. There is no individual overseeing the care process. This is largely the responsibility of my mother and her husband. Like most people with chronic illness, they have discovered their own solutions, ways to solve problems they encounter with drugs, services and insurers. She has a marker board for her list of medications and appointments. Although we all have financial worries, hers seem somewhat more acute and ever present.

After much cajoling, she returned to work last September. She teaches a full class at the University of Arizona on printmaking (see picture below). She asked for and received a student helper in the classroom and one to assist her in making art in her studio from the university’s disabilities resource center. She has had to be creative in the process. She participates in the process but needs to be collaborative. I have asked her to write a piece on how the process of art has changed for her – both as an able bodied person and now as one with disability. She is thinking about it.

After much cajoling, she returned to work last September. She teaches a full class at the University of Arizona on printmaking (see picture below). She asked for and received a student helper in the classroom and one to assist her in making art in her studio from the university’s disabilities resource center. She has had to be creative in the process. She participates in the process but needs to be collaborative. I have asked her to write a piece on how the process of art has changed for her – both as an able bodied person and now as one with disability. She is thinking about it.

Her health remains good. She deals with occasional spells related to body temperature regulation and hypotension, but overall has not had common complications of many quadriplegics.

I would like to make one final comment regarding quadriplegia. The word “complete” is a misleading term that should be abandoned. On hearing this term, many of the nurses we met at the Barrow gave up on my mother assuming she would never get any further recovery. Patients with cord injuries are not complete or incomplete. They are transected (the cord has been cut) or they have an injured but intact cord remaining. There is no way to know at the time of an acute event whether the cord is cut or simply injured without advanced imaging. For those that are not transected, like my mother, every day is a chance to get a new skill, to recover lost functionality. Hope is a powerful motivator.

Replacing the shoebox and other issues for the future

Along with my clinical responsibilities, I do research related to the nexus between humans and computers, asking how data and process can be captured to improve care. I have a particular interest in tools enabling patients to participate in the process of wellness. I find it more than a little ironic that my mother continues to use paper and a marker board to manage her care. My mother’s experience reflects some of the basic problems with the current approach to healthcare delivery. In particular, her care was optimized during the acute phase, but is relatively disorganized now that she is coping with a chronic disability. Further, patient and family efforts to optimize care are not supported by participatory tools.

The current administration is spending billions of dollars to improve the healthcare infrastructure. There is an expectation that within 5 years every medical practice, from large hospitals to small clinics will be using some form of electronic record. This should improve care and hopefully reduce costs. However, in many ways, this is more of the same, an effort focused on the provider, the apex.

Patients and their families need a similar effort that is directed at helping them care for themselves. Currently, a shoe box is the best we’ve got. This “box,” full of notes from previous hospitalizations and clinic visits along with CD’s of images, is all too common. The patient comes to clinic, hands over the box and expects the provider to make sense of the records and arrive at a plan moving forward. With most appointments no more than 30 minutes, this is not going to happen. There are a number of companies offering to digitize records. This is not the answer. Providers need relevant summaries, dashboards, of how the patient has been doing.

There have been some recent signs of change. In 2006 the FDA suggested “observations of daily living” (ODL) become part of new drug and device evaluations. It makes sense to ask the consumer (and not just the researcher) how they are doing with products. The private sector has also made efforts. Microsoft, Google, and Relay Health have all introduced solutions that capture information about and from patients. However, these are not simple to use or significantly relevant to merit sustained traction.

Solutions need to be transparent. Many people with chronic illness are from a generation that is not comfortable with the internet. Even cell phones are a bit foreign. My father-in-law often uses his cell phone as a one way device. He makes calls and then turns it off to save the battery. My mother is willing to participate, but the process has to meet her workflow. My personal belief is that the TV will be the final common device. Everyone can work a remote. It will work with other devices in the home through Bluetooth. It will remind us when to take pills. It will allow us to meet with our doctor while at home.

The cable box is not a one way device. I Skype with my mother, but she has to turn on the computer, start the application, turn on the camera. She should meet me and others on her healthcare station. Voice recognition software also needs to improve. It is designed for business, but there are other large markets. The software needs to be hands free. She uses it, but not without assistance. Later this year she and I will be experimenting with a new box from Cisco that should get us closer to this vision.

Solutions need to consider the patient’s ecosystem rather than their illness. My mother and I don’t care about quadriplegia, but rather living with quadriplegia – how she copes with the various difficulties in her effort towards wellness. Most approaches do not consider ways to leverage the family and related opportunities or local resources to stay well.

I was told a story by a father of a juvenile diabetic. His daughter had slipped into coma several times in the past. Out of concern, he found himself calling her once a week at odd hours to check on her. The daughter viewed these calls as an intrusion on her independence. A solution that called out to the father, but only when there was something wrong, would have provided a margin of safety for the daughter while addressing her family’s concerns.

Similarly, advanced electronic platforms message or alert a nurse if the patient’s weight, blood pressure or sugar is abnormal. Why are family members not included in the messaging layer? Families are cheap and the most vested in the patient’s well being.

My mother has to find solutions to problems on her own – where to find goods and services, how to deal with common problems. Google Maps can find and rate a restaurant or the nearest gas station. Why not use local based services for physicians, wheel chairs, etc.? I raised this issue with Google Health two years ago…nothing yet.

The patient is the largest untapped resource in the healthcare debate. After all, they are the most vested party, the one with the illness. Providers are merely a part of the process along the way.

Great post, Alan. One thing that was striking to me is the lack of care coordination. Where was her PCP?

Alan,

Thank you so much for sharing your story. There are so many layers to it that I wasn’t sure where to start, but serendipity pointed me to a related post by Andrew Wilson:

Check-ins for Health

http://andrewpwilson.posterous.com/check-ins-for-health

He talks about how geolocation/social network services like Foursquare might be deployed to create consumer reviews of health services.

Phil Baumann has also written about the health applications of Foursquare, in a more metaphysical way:

Foursquare Is Powerful Enough to Cure Insomnia and Depression

http://philbaumann.com/2010/01/17/foursquare-is-powerful-enough-to-cure-insomnia-and-depression/

(I’m totally the Mayor of Too Much Coffee right now, for example.)

I’ll repeat the comment I posted on Andrew’s blog so we can discuss it here, too:

Why is it that we can easily pull up restaurant reviews but not nursing home reviews?

Of course one answer is that many more people frequent restaurants — and it’s more fun to review food than to review health care services — but among those who care, such peer-to-peer advice would be welcome. Pew Internet survey data shows, for example, that chronic disease makes it more likely for someone to consume user-generated content and to participate in the online conversation. These are people who are generally at the low end of tech adoption – among the least likely to have an internet-enabled mobile device, for ex – but they are taking advantage of what they have. As I put it recently, they are evolving (and why can’t online services/health care services evolve too?)

Hi Alan!

Thank you for your beautiful, deeply personal and very powerful post. The saying that has appeared countless times on the ACOR communities for 15 years applies remarkably to it:

Sorry you have to be here but delighted you found us!

What an amazing story.

For anyone having to deal personally with a catastrophic or life-threatening medical condition there is a time before, The Moment, when you realize you must take charge in order to get optimal care, and then the rest of your life. Your post seems to be yet another description of this essential evolution. It’s hard to imagine that coming from your position of medical excellence you still have to deal with the terrible realities of the current US system where patient participation is not actively encouraged.

More comments later!

Hi Alan, Thanks so much for sharing this with me. Per all our previous conversations, primarily around my healthcare issues, this really hits home. This “electronic connection” cannot come soon enough.

Really enjoyed this Alan. Your mom’s story is very inspirational.

Alan, a beautiful story built on the tragedy of your mom’s loss.

I am now in a similar position watching, recording, ‘stewarding’ my mothers process as she’s been newly diagnosed with breast cancer.

I know your comment: ‘Solutions need to consider the patient’s ecosystem rather than their illness’ was offered in the context of the downstream chaos associated with non-acute, chronic needs of patients, yet don’t omit the real time chaos of the acute episode absent proactive, patient centered coordination of needs.

Even in a cancer center, domiciled in a ‘system’ claiming rave third party reviews including HIMSS EMR adoption status, has many ‘patient experience gaps’ yet to identify and address.

Thanks Alan!

Alan,

Thanks for writing about Mom. As I read the beautifully written story I found it difficult to relive but inspiring as well. It is amazing to watch our mother rebuild and excel in her personal and professional life. Thank you for looking for solutions for her, it gives us all hope and her the power to hopefully improve her quality of life.

love from your sister Rachel