Update: The NLM released new widgets on July 14, along with a redesigned MedlinePlus site. (Read @eagledawg‘s take on these new tools, as well as her response to this post.)

Speaking to the senior staff of the National Library of Medicine last week was like going before the best kind of murder board. Picture it: 30 of the nation’s smartest health information mavens around a polished conference room table, asking me sharp questions, suggesting new lines of inquiry, and offering their own insights. In other words, heaven.

Our jum ping-off point was the Pew Internet Project‘s latest research on internet penetration, mobile use, and the social life of health information. Here are my notes from Thursday’s meeting and some research questions I’m considering:

ping-off point was the Pew Internet Project‘s latest research on internet penetration, mobile use, and the social life of health information. Here are my notes from Thursday’s meeting and some research questions I’m considering:

One of my hosts, Robert Logan, had seen my Patient Is In speech at Health 2.0 last fall and asked me to address similar issues — how people become activated seekers of health information. He also complimented the Pew Internet Project’s steady stream of data releases, which we are able to maintain because of the generous support of the Pew Charitable Trusts and the ingenuity of our small staff to squeeze the most out of our research budget.

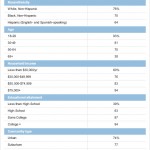

My first illustration was a perfect example of a frequently-updated Pew Internet resource (internet penetration in the U.S.) and how the data can be viewed through a health lens.

Many health organizations, including the NLM, want to reach different age groups — online, offline, on a mobile device, etc. This chart shows that age continues to be a significant predictor for internet use: 93% of 18-29 year-olds go online, compared with just 38% of adults age 65 and older, for example. Education is another undeniable force: 94% of those with a college degree use the internet, compared with 63% of high school graduates (and just 39% of adults with less than a high school education).

I noted, however, that although most of our “oldest old” and least-educated are offline, they may have what we call second-degree internet access via their loved ones and friends. Half of health searches are conducted on behalf of someone else, not the person with their fingers on the keys, for example.

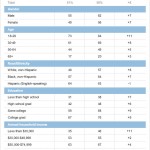

My second illustration was the first chart from Pew Internet’s Generations Online slide deck:

All the data in that deck is from 2008-9, but the trends hold true for 2010 (with significant increases across the board for social network site use).

When segmenting the online audience, remember that most internet users age 65+ stay in the shallow end of the pool — email and info-gathering — while younger internet users tend to venture to the deep end — uploading video, creating blogs.

There are exceptions, of course, and Pew Internet is tracking what may be an X factor: wireless internet use. We have identified a “mobile difference“: wireless connections have a significant, positive effect on an internet user’s likelihood to engage in social media.

I noted that we also have identified what might be called a “diagnosis difference.” Our research on chronic disease found that living with such a diagnosis also has an independent, positive effect on a person’s use of social media for health.

This inspired a good sidebar discussion about patient activation, and what role it plays in online engagement with health. The Center for Studying Health System Change has found that just 41% of patients have the knowledge, skills, and confidence to manage their health, with cancer being at the “most activated” end of the spectrum and depression at the “least activated” end. (For background, please see “Development of the Patient Activation Measure…” For an overview of what I think, please see “Mobile could be a game-changer…” And I’d welcome other views and citations.)

Forrester has another helpful way to picture social media engagement: as a ladder, which people can climb up or down as their usage changes. I included the illustration from Josh Bernoff’s blog post, “Social Technographics: Conversationalists get onto the ladder” as my third illustration.

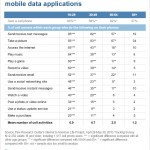

Next I featured two charts from my colleague Aaron Smith’s report, Mobile Access 2010.

Next I featured two charts from my colleague Aaron Smith’s report, Mobile Access 2010.

First, I discussed the data showing changes in wireless internet use by demographic groups between April 2009 and May 2010. For example, in the spring of 2009, 57% of African American adults went online with either a wifi-enabled laptop or a cell phone. In 2010, their use jumped to 64% — a notable increase in just one year.

Fully 84% of 18-29 year-olds now go online wirelessly, compared with 69% of 30-49 year-olds, 49% of 50-64 year-olds, and 20% of adults age 65 and older.

I’m particularly struck by this stat: 20% of wireless internet users go online exclusively on a cell phone.

I summed it up in a tweet: “Information purveyors: Go mobile. Everyone else is: http://pewrsr.ch/Mobile2010”

The next chart focused on mobile activities among various age groups, particularly the stark differences between adults ages 18-29 and everyone over 30.

The next chart focused on mobile activities among various age groups, particularly the stark differences between adults ages 18-29 and everyone over 30.

Fully 95% of 18-29 year-old cell phone owners send and receive text messages (and we know from our Teens and Mobile Phones research that the volume of texts is probably pretty high). Forty-eight percent of 18-29 year-old cell owners say they access social network sites on their mobile phones. And 40% of this age group watches video on their phones.

Cecilia Kang‘s Washington Post article, “Going wireless all the way to the Web,” illustrates the trade-offs some people are making between small-screen wireless options and the luxury of a big-screen connection. As one 16-year-old said of sipping information through an iPod: “It’s way cheaper than a computer, that’s for sure,” he said. “But you also have to have a lot more patience.”

Looking at this data is like watching the effects of erosion on a coastline: the information landscape is shifting and the changes are picking up speed. As I’ve said before, if your organization’s information isn’t accessible and readable on a small screen, it’s not available at all to some groups. Now is the time to make changes to online services to account for both the popularity of mobile access and the way it is changing us as internet users.

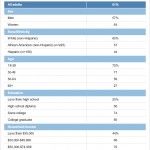

My next illustration displayed the demographics of those who look online for health information, which mirror the demographics of the internet population (taking 10-20 points off the top for those who do not engage with health online — for example, older internet users who rely primarily on offline sources).

My next illustration displayed the demographics of those who look online for health information, which mirror the demographics of the internet population (taking 10-20 points off the top for those who do not engage with health online — for example, older internet users who rely primarily on offline sources).

Two-thirds of those who look online for health information usually talk about it with someone else. The Pew Internet Project will focus on research questions about the who, what, where & when of those health conversations in an upcoming survey. But the questions are pertinent to the NLM’s mission, too: What are people saying? Is the NLM helping to seed the conversation? How are you contributing to the spread of facts, the spread of science, the spread of evidence?

Since these demographics were nothing new to this group, I quickly moved on to our more unique data set, which focuses on people living with chronic disease.

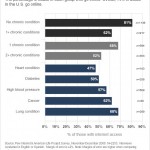

One-third of U.S. adults are living with a heart condition, lung condition, high blood pressure, diabetes, cancer, or a combination of those diagnoses. Of those, 62% have access to the internet, compared with 81% of adults who report none of those conditions.

Statistical analysis finds that chronic disease has an independent, negative effect on someone’s likelihood to go online.

Statistical analysis finds that chronic disease has an independent, negative effect on someone’s likelihood to go online.

However, once someone does have internet access, chronic disease has an independent, positive effect on an internet user’s likelihood to use social media for health: to blog, to contribute to online health discussion, to access hospital reviews, doctor reviews, and podcasts. (For more on this topic, please see Chronic Disease in Data and Narrative.)

My take-away: Keep the reality of the current population in mind, but don’t count out the power of a life-changing diagnosis to affect the way someone gathers and shares information.

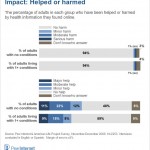

My closing slide is one of my favorite charts from our report, Chronic Disease and the Internet. Few people report harm when it comes to health information online, many more people report that it has helped them or a loved one.

My closing slide is one of my favorite charts from our report, Chronic Disease and the Internet. Few people report harm when it comes to health information online, many more people report that it has helped them or a loved one.

The ensuing discussion allowed me to bring up some of my favorite examples outside the Pew Internet Project’s research scope:

Nicholas Christakis & James Fowler’s book Connected showed how obesity can spread through a network – but so can happiness. Behavior – both good and bad – can be catching. How can the NLM seed conversations happening online and offline, to spread good information and good behaviors?

The FDA and CDC teamed up to spread the word about the Salmonella outbreak last year, fanning out across platforms to get the word out, including the development of a recall widget. How can the NLM leverage the power of mommy-bloggers or their equivalents?

Health 2.0 Europe was alive with debate about government’s role in health and health care, including some heated exchanges about how to oversee the quality of online information. What if the NLM harnessed American ingenuity and the EU’s information quality focus? One answer: Pillbox

Google features MedlinePlus among the first results for health condition searches, as we’ve discussed on e-patients.net. Now Google’s top results for drug searches also yield links to NLM pages, as reported by Eileen O’Brien on the SirenSong blog. Should the NLM seek more placements such as these? Should the NLM maintain its own brand or should the National Institutes of Health emerge as the stronger, overall brand?

Procter & Gamble, among other companies, is scaling up their use of social media and cutting back on traditional market research. Their new research motto can be summarized as: “Listen more than ask.” How can the NLM harness the same techniques?

And as I so often do, I closed with this question: Health is social. Health is mobile. What are you spreading?

Wow…a ton of great info here. Regarding the NLM/NIH brand question, I’m of the mind that consolidating the images, at least as far as online and mobile health info, would be greatly beneficial. Imagine if all the talent working on this under various institues joined resources, eliminated duplication, and worked together? It’s not that simple, I know, but it’s a conversation people should be having.

Erica,

Thanks so much for saying out loud what lots of people are saying to me in private.

It’s complicated, political, and there are no easy answers, but we should still be brave enough to ask that key question: What if?

What lessons can dot-gov learn from the dot-com world, which can spend $$$ on image consultants, etc?

See my “Part I” comments on NLM-NIH branding and innovation below.

On NLM/NIH branding and innovation in the consumer health realm (Part I)

It’s hard to know where to begin here. The original missions of NLM and NIH, respectively, were to serve the information and research (funding) needs of health care and other biomedical professionals. NLM later developed MedlinePlus for consumers and each of the 27 or so NIH Institutes and Centers (“ICs” in NIH jargon) independently added consumer health info to their own web sites over time. One big difference between NLM and the rest of the ICs is that most of NLM’s content is licensed from copyrighted commercial sources, repackaged and given NLM’s imprimatur (or “brand”) as high-quality health info. In contrast, all of the other ICs produce their own consumer content as non-copyrighted “government work” and provide it on their own web sites without any systematic coordination with the NLM. Because of the separate missions (and budgets) of NLM and the other ICs, there has been little incentive to coordinate, let alone innovate, across these organizational boundaries. We have studied this information space intensely and the results aren’t encouraging (more about that in Part II).

The situation is even more discouraging when you consider that NLM and NIH are both divisions of DHHS which also includes the CDC and FDA, each of which originate and publish their own consumer health info, uncoordinated with NIH/NLM. How does any of this relate to HealthFinder.gov? It doesn’t. Does any of this relate to the Office of the Surgeon General? No, not at all. So here we have at least 30 different departments in DHHS each independently developing and serving up it’s own consumer health info without any content coordination. The only things that are coordinated by DHHS are accessibility standards like grade-level readability and “Section 508” compliance.

Consequently, it would literally take an Act of Congress to “authorize” (more gov’t lingo) NLM/NIH to do anything differently. Even with “authorization,” nothing would really happen without a corresponding “appropriation” ($$) to finance the activity. As one Congressman explained it simply to me, “authorization” is like having a father’s permission to marry his daughter; “appropriation” is getting him to also pay for the wedding.

If this is only Part I, I can’t wait to read Part II.

I knew some of this, but not the full story. I think the GovLoop community is going to take up some of these questions in their discussion forum since this issue is not limited to HHS & health info, but is threaded throughout the federal gov’t (and any huge org, I bet).

Thanks so much, Mark!

Part II

Susannah, you probably know that the actual, individual NIH institutes are historically based on related organ systems (e.g. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute) and/or disease categories (e.g. National Cancer Institute, National Institute for Mental Health). These categories function to concentrate expertise for developing programmatic (research) goals, organizing funding solicitations, conducting grant application reviews, funding academic researchers, etc. but were never conceived or designed to mirror your famous “top ten” reasons why American adults search for online health information. Thus it’s almost impossible for a consumer to navigate the 27 sites to meet their needs, particularly if their disease or condition involves signs and symptoms that cross the somewhat artificial, categorical boundaries.

For example, there is no “National Institute of Pregnancy.” A woman who has just been told that she may have a common, but serious, complication of pregnancy called “preeclampsia” would have to search at least four internal NIH web sites and one external (but still DHHS) web site to locate all of the relevant consumer or e-patient information. For pregnancy-related problems in general, she would have to search NICHD (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development). Because preeclampsia involves high blood pressure and impaired kidney function, she would also have to search both NHLBI (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute) for information on high blood pressure and NIDDK (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases). Then, if she wanted information on treatments, she would have to go to FDA.gov because none of the diseases at NIH.gov are linked to information on drugs, side effects, brand names, generics, etc. provided by the FDA. For additional treatment options, she would have to return to NIH and search NCCAM (National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine). Then it would be up to her to integrate and prioritize the results of all these separate searches. There is only one way (see Part III) to cross-query all of these government information sites in one step, but neither the NLM nor other NIH Institutes provide this or any other type of systematic cross-referencing or hyper-linking.

It’s little wonder then that most consumers would just type “preeclampsia” into a general search engine and, if it were Google, end up at one of the hand-picked “brands” that Google has chosen to appear at the top of their search results (such as NLM which, as I’ve explained, contains none of the information at the other 20+ NIH ICs even though they’re all part of NIH, located on the same physical campus in Bethesda and right down the street from the FDA).

So how do we recover and maximize the value of all of these independent but overlapping sources of gov’t consumer health information that our tax dollars have already paid for and continue to sustain? As I’ve said in Part I, there are actually financial disincentives and organizational barriers for NLM/NIH to overcome these problems, let alone address them across all of DHHS. One approach would be the political process to lobby legislators and the executive branch to address these issues. If this long and complex process did successfully produce the required authorizations and appropriations, the agencies would still have to deal with all of the “change management” issues required for successful implementation and adoption. I describe another approach in Part III.

This is such a big, hairy challenge I’m starting to think we need some people in on it who don’t know what they can’t do and aren’t tied in to any one organization (ie, hackers in the best sense of the word).

Is this a job for the Health 2.0 Developer Challenge?

http://health2challenge.org/

Susannah, let me save you a little time. We spent many months developing and optimizing sophisticated web crawlers to identify and extract consumer health info from US gov’t web sites. At NIH.gov alone, we analyzed more than two million pages of information. The information was so non-uniformly organized, sometimes mislabeled and oftentimes co-mingled with non-consumer information that, from an information retrieval point of view, it was nearly impossible to automate the process. We have lots of suggestions for how this situation could be improved (and tools to do it). More results of our analyses in Part III, which I’m working on now (as a preview to a peer-reviewed publication).

I completely concur with the complexity of navigating so many .gov sites for information on preeclampsia. As the only patient advocacy organization addressing this rather common complication of pregnancy, we live that pain every day! The only exception I would take to your astute comments is that the average consumer does in fact turn to Google and other search engines and if they’re smart enough to skip the advertisements, would come immediately to our non profit organization’s website for accurate and consumer-friendly information.

Our website – godsend that it is for our women – is old and desperately in need of upgrading, mobil-izing, etc. which I’m happy to report we are in the process of doing. If any of the experts on this thread would be willing to provide input or expertise for this undertaking, we’re all ears.

We are, as far as our analytics can tell, the #1 source of info on this important topic, trying to stay relevant and life-saving for the millions of moms and babies impacted each year around the world.

Loving this entire thread… accessible and digestible consumer health information is central to our “empowered patient” theme.

Sorry, need to reply to my own reply. You can click on my name to go to our website, but I should have made it more apparent. The Preeclampsia Foundation can be found at http://www.preeclampsia.org. Any search would have taken you there, too. Thanks for indulging this brief PSA. (we are a 501c3)

It just occurred to me that most of what I’m posting here is derived from an unpublished paper I’ve written. Would the Journal of Participatory Medicine be interested in publishing the full, referenced account? Of course, the JPM is not indexed by NLM/Medline so I’m not sure I’d want to publish there ;-)

For a short history of online health info at NLM, from pre-Internet through 2007,

see http://bit.ly/aM7EGn

(table and text on page 254).

I have (almost) fond memories of Grateful Med :)

There *must* be a good story to explain the name for the original NLM search – if that’s what it was?

I think it was a play of the popularity of “The Grateful Dead.” (Look it up in Wikipedia if you’re too young to know who they are ;-)

I wasn’t at NLM then and I don’t know who came up with the idea. But it must have sounded pretty “cool” and “edgy” at the time.

Part III — Where we are now

After performing due diligence on the unmet needs of non-professional health info seekers (some of which is published here http://bit.ly/aM7EGn), Alan Littleford and I spent the next two years devising new ways to clean up and reorganize gov’t consumer health info space. My background is here, http://www.markboguski.net; Dr. Littleford was the co-Founder and Chief Technology Officer of Healthscape, Inc. Prior to this, he held a number of key positions in the IT industry as Principal Architect, Lead Developer or Founder at companies such as Cogent Software, Sitka (a subsidiary of Sun Microsystems), Siebel Systems and Network Associates. Alan has been a consultant for a number of both major companies and technology start-ups in Silicon Valley and elsewhere.

Building on the foundation of the UMLS ontology, we have identified and incorporated nearly 1500 diseases, conditions, medical procedures and other health topics written for consumers from all NIH Institutes and Centers (ICs, excluding NLM). We have also incorporated “package insert” information for the nearly 4300 approved drugs from FDA.gov. All of this content has been automatically organized using our Medical Ontology Engine which identified approximately 71,000 known medical terms and created a network of about 111,000 explicit connections among various medical conditions and their treatments. This network of linked medical knowledge is “self-learning” as it was designed to continuously improve and expand 1) as users interact with the system and 2) as the system ‘digests’ feeds from knowledge sources such as the Public Library of Science (PLOS), ClinicalTrials.gov, GeneTests.org and other high-quality, web-based sources of medical information.

All of this is searchable on our website http://www.ResoundingHealth.com

I. Coverage of Health Topics across NIH Organizational Boundaries -Example

Enter “autism” as the search term and then click on the “casebooks” tab to discover that autism is independently covered by 28 separate articles distributed over five different NIH ICs including NHGRI (National Human Genome Research Institute), NINDS (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke), NIEHS (National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences), NIDCD (National Institute of Deafness and Communication Disorders) and NIMH (National Institute of Mental Health). None of these articles are content-coordinated and you’d be hard pressed to find any cross-referencing to similar information on different NIH web sites. There are no links to the proprietary health information products licensed by NLM and made available through MedlinePlus.

II. How Many Health Topics has each Institute Published? -Examples

Enter an institute’s acronym into the search box and select the casebooks tab to see the results. For example, NICHD (National Institute for Child Health and Human Development) publishes information on 97 different consumer health topics including diet, nutrition and obesity, infertility, birth control, developmental disabilities, lactose intolerance and “tummy time.” Likewise, NCI (National Cancer Institute) has 233 articles on various malignancies, both common and rare.

We encourage you to investigate health topics of personal interest or importance and let us know if you discover anything unusual (good or bad) either with our system or its NIH and FDA-derived content. Better yet, create a casebook on your topic (containing, for example, comments and ratings on various preeclampsia web sites) and share it with everyone.

There are two basic types of casebooks: 1) resource casebooks containing non-copyrighted, but fully attributed, gov’t consumer health information and 2) user-generated casebooks containing any health information they’ve found useful on this site or anywhere else on the web. Various tools for sharing the information with others, including embedding links to it on other sites, are available.

Casebook technology allows you to create and annotate custom remixes of the information for your own purposes (your content is all automatically organized, behind the scenes, by the medical ontology engine, thus relating it to all other medical knowledge on the site). Think of this as being able to create new, virtual consumer health institutes on demand and suited to individual needs or special purposes.

The Resounding Health website is currently a technology demonstration and research tool. It is used as the research platform and resource for all of the stories on our consumer education and outreach site, http://www.CelebrityDiagnosis.com, many of which bring the attention of average consumers to gov’t health information that they’d be hard-pressed to locate any other way.

I’m a huge fan of Gary Price and his site, ResourceShelf.com, so I have to share his post responding to the points I made in my presentation at the NLM:

http://www.resourceshelf.com/2010/07/14/mobile-social-health-at-national-library-of-medicine-nlm-susannah-fox-speaks-two-presentations/

Here is an excerpt:

1) When it comes to consumer health NLM or MedlinePlus or something else (but not NIH) must become a synonym for health info. They must get to the right people and get them talking. This is what another well-known company did, they’re name is Google.

2) Differentiate Between PubMed and MedlinePlus (The Right Tool for the Right Job)

3) Should the NLM seek more placements [did NLM pay for these placements or are we talking organic search] such as these? Should the NLM maintain its own brand or should the National Institutes of Health emerge as the stronger, overall brand?

They should must maintain their own brand.

1) Search results can change at a moments notice.

2) Not everyone uses Google

3) Is their just one book about health in the bookstore?

3) When Yahoo begins using the Bing database that will increase market share for Bing results. How is NLM Preparing?

4) Again, Google should be used as an example on how to reach out and get “influencers” to use the product and tell others about it.

Bottom Line: NLM has to be both a sly marketer and a teacher. Marketing their wonderful products and services and training people why they are better and that they are not hard to use. Of course, this must be done on a limited budget vs. other well-known and commercial health sites.

This podcast was recorded on the same day as the NLM meeting and I talk quite a bit about what was discussed (and who doesn’t love listening to TogoRun’s Banks Willis’s deep Southern accent?)

http://togorun.net/blog/2010/07/susannah-fox-on-the-rising-role-of-social-media-in-health/

Mobile literacy is a cornerstone of this vision. This includes understanding the importance of the growing mobile culture and impact on both users and organisationally to promote effectiveness and introduce efficiencies. The action of building both infrastructure and a culture of engagement will pave the way to more efficiently and effectively meeting that need in the future.