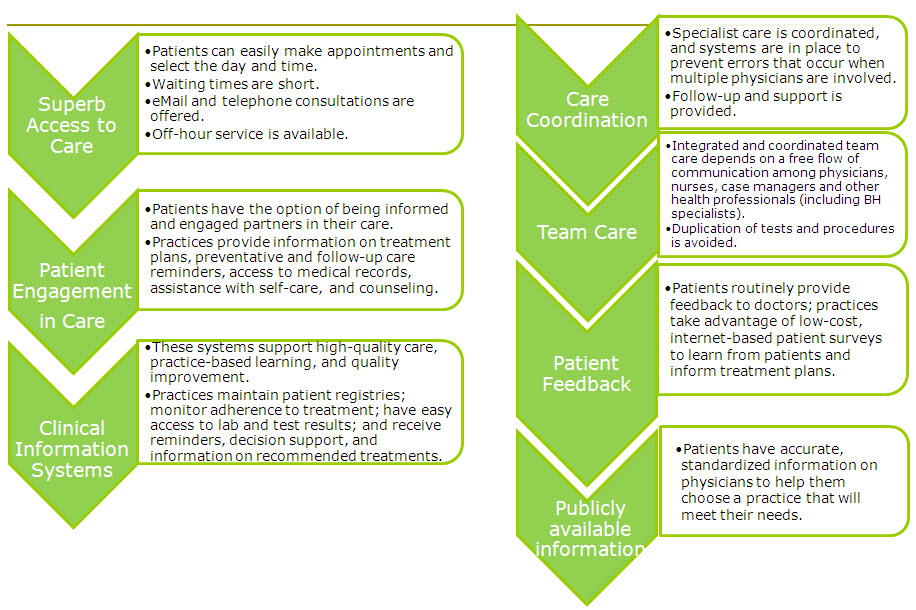

I ran across a graphic today that warmed my heart:

Recognize that agenda? (Click to enlarge if you want more clarity.) Sure is a lot of what we’ve discussed.

Pie in the sky, tough hill to climb, nice idea but not feasible, right? Wrong. Thursday I’m at a quarterly meeting a group that’s already making this happen. They’ve got demonstration projects, measurable results, tests of different payment models, the whole nine yards. They’ve been working on it for five years, and I don’t understand why none of the better-health-minded people I talk to have ever heard of the group.

It’s the Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative, PCPCC. They have great news, and we should all learn what they’ve been learning, so we can work on the next great leap forward.

I also attended their April meeting in Washington. (I’ve been an informal “patient advisor” to them for two years.) Here are the slides Executive Director Edwina Rogers presented then. Look at all the work they’ve been doing and the results they’ve produced.

Look at all the activity! Look at the many endorsements! Other presentations that day reported on the many subgroups’ activities and results.

PCPCC has appeared a few times in these pages, most memorably in November 2008, when their chairman showed his stripes. Our short post:

Paul Grundy MD, of IBM, chair of PCPCC, is interviewed in the current Crain’s Benefits Outlook, a business publication about employee benefit programs. This quote alone is worth the price of admission:

I can buy a damn good amputation for my diabetic, but what I can’t get is a good system in place to prevent my diabetic from needing the amputation. We don’t reward a system in which comprehensive coordinated care and robust prevention is valued.

Amen. What are we thinking, insurers, when we fund treatments instead of preventing them??

Why has IBM led this? As I posted on my own blog in May 2008, employers (especially big ones like IBM) pay the lion’s share of insurance costs; IBM spends $2 billion a year on healthcare worldwide. They also have data (lots of data; this is IBM) about what works around the world.

Kudos to the people who’ve been doing this work. Please spread the word to everyone you know who’s involved in improving healthcare – everyone should know these facts!

I’ll post an update after tomorrow’s meeting.Update: just as this “went to press” an email arrived with speakers and slides from the next meeting, July 22.

As a member of PCPCC, I’ve expressed some of my concerns in the group’s on-site forums. I love the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) model, but it has a few sizable holes that someone needs to address and fill before they create structural instabilities that bring the whole thing down.

(1) I think (as Trisha Torrey noted on the PCPCC site) that PCMH confuses people. When I try explaining it, the first thing they want is to see a PCMH. PCMH isn’t a place (although, I suppose you could build a single PCMH based entirely around one medical center). PCMH is a concept based on teamwork. Maybe it should have been called the PCMTeam. Even that’s misleading, because

(2) It’s not a medical-centric concept. It’s a health-centric concept. I’m not the first to note that “medical” should be replaced with “health” in the name. So, instead of PCMH or PCMT, maybe PCHT would be better. Unfortunately, the concept is stuck with its name: PCMH. Just remember to remind folks that it’s a patient-health-centered team concept.

(3) PCPs. The first principle of the PCMH is that every patient has a solid relationship with a PCP. That PCP has to be connected to patients via email or text, and someone (the PCP or her PA or her NP) has to be on-call 24/7. This is a big stumbling block in most areas. I can’t even find a decent PCP, much less one who’s email- or text-friendly and has a 24/7 person on-call. Of course, there’s only one PCMH in Texas, and it’s in the North (I’m in Austin, just south of Central Texas).

(4) Whole person orientation, part 1. Whole person orientation, in my opinion, is more important than the PCP, and most PCPs really don’t have much training in nutrition and fitness, which are the cornerstones of whole person orientation. Nutritionists could be added to the PCMH, but that might jack up the price. Besides, nutrition has too many holes, from an evidence-based POV. How many different food pyramids do they have to build before they figure out that they need some serious research?

(5) Whole person orientation, part 2. Fitness. Fitness should mean wellness checks, cholesterol screening, BMI checks, the attention of trained kinesiologists (the physical fitness kind, not chiropractic), and rewarding such things as use of gym memberships, aerobic training, yoga, and activity in published walks, runs, marathons, bike rides, and triathlons. So, okay, the PCPs can do cholesterol screening and BMI. As with nutrition, fitness as a science suffers from a serious dearth of research, with what exists being largely lacking in controls.

(6) Quality and safety, part 1. Safety first, as they say. The WHO safe surgical checklist has been tried out in only 1400 hospitals and surgical centers out of over 5000 in the US alone. It shouldn’t be so hard to test something so simple and inexpensive. This is especially exasperating when the only consistent objection is from surgeons afraid of losing autonomy in a situation where teamwork is safer and more efficient than autonomy. Also, if you think that’s just a nit compared to the Patient Safety Big Picture, just look at the U.S. News and World Reports recent report on top hospitals in the U.S. Most of the number one hospitals listed for various fields are listed as having patient safety ratings of LOW or LOWEST. That’s just wrong.

(7) Quality and safety, part 2. As a former-quality-assurance agent for a major Three-Letter-Corporation (TLC, thank you very much, Mr. Hurt), I am sick of the typical attitude toward quality. Everyone wants quality (quality is job one! the quality goes in before the name goes on!) but (a) they want it for free, and (b) they want it slapped on at the last minute. Quality is either part of the process from the beginning, or it’s a sham. Quality isn’t bondo, a splash of primer, and a top coat that you can slap on at the end to make everything look nice. If the chassis is a rust heap, the integrity of the primer coat doesn’t mean squat. Meaningful use is a great example. For once, the government set down some requirements for what constitutes meaningful use (i.e.–quality) from EHRs, and everyone wanted their share of the money while complying with as little as possible. The result was a watered-down version of meaningful use. At least some of the requirements remained intact (for now).

Now, some folks will look at this list and claim that I’m kvetching for the sake of kvetching. I can’t claim that I don’t enjoy a good argument, but I mean a real argument as in the original Latin meaning of the root arguere “to clarify.” Anyway, despite the length of my complaints list, these are holes in PCMH, not major structural defects. I still want to be a patient in a PCMH, even if these elements aren’t yet repaired. Okay, well, maybe the whole person orientation problems need more work than the rest. Even there, though, the PCPs are using what knowledge they have to help with fitness and nutrition, and it’s helping. I just think everyone could benefit from a bit more help.

Hey Dennis – thanks for the meaty detailed add. Couple of thoughts –

1. Slide 10 above cites the 40+ year history of the term “medical home.” (I don’t disagree with you – I face the same obstacles every time I introduce the idea to people – I’m just noting the historical explanation.)

2. As I’m sure you know, the general idea of PCPCC’s demonstration projects is to gather evidence to persuade both policy people and doctors that this approach works, and is thus worth “rewiring” our operations.

The best info I heard on this yesterday was a detailed description of the care team in a particular pilot project (1 PCP, 1 physn assistant or nurse practioner, 1 admin, etc) and the data on results: slight increase in total number of claims and office visits, dramatic drop in hospitalizations, and resulting significant drop in total cost.

I would hope (and I say that with eyes open) evidence like that will influence right-minded planners, especially as the vise continues to tighten and leaders eventually get to where they’re willing to try new things.