Joe Kvedar asks an excellent question in his post, The Next Phase of Connected Health: Connected Personalized Health:

What are the best variables to consider when taking connected health programs from pilot to scale?

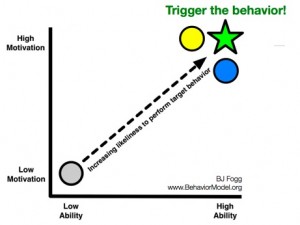

He imagines a matrix with three axes: severity of chronic illness, patient readiness, and technology readiness. That makes sense to me, as did BJ Fogg’s Behavior Model when Alexandra Carmichael described the three elements to me in words: Motivation, Ability, and Trigger.

But I felt like I could actually apply BJ’s model after seeing his simple diagram:

The element Joe is adding, which is key to health interventions, is the severity of illness (or seriousness of diagnosis). That echoes the findings of the Center for Studying Health System Change: 41% of U.S. adults are “activated patients” (the rest tend to be passive and may lack the confidence to play an active role in their health). Cancer patients are among the most activated, whereas people living with depression are among the least.

The element Joe is adding, which is key to health interventions, is the severity of illness (or seriousness of diagnosis). That echoes the findings of the Center for Studying Health System Change: 41% of U.S. adults are “activated patients” (the rest tend to be passive and may lack the confidence to play an active role in their health). Cancer patients are among the most activated, whereas people living with depression are among the least.

It also resonates with the Chronic Quadrangle described in The Innovator’s Prescription (p. 161 if you are a total health geek and have the book handy). Diseases with immediate consequences vs. deferred consequences are categorized, cross-factored by their dependence on technology dependence vs. behavior dependence. Celiac disease is one example of a condition requiring extensive behavior change and immediate consequences for not complying with the best known therapy. Osteoporosis is on the opposite end of the quadrangle: minimal behavior change is required and consequences are deferred.

I would add yet another question to the conversation about scale: is the application social or not? In other words, is it a grab-and-go information hub (like Google) or is it a place where users are invited to sit down and stay a while (like Facebook)?

Adam Rifkin’s essay, Pandas and Lobsters: Why Google Cannot Build Social Applications… is a must-read on this topic:

After researching what pandas do all day, I was struck by how panda-like we are when we use the Internet.

Roaming a massive world wide web of forests, most of our time is spent searching for delicious bamboo and consuming it. 40 times a day we’ll poop something out — an email, a text message, a status update, maybe even a blog post — and then go back to searching-and-consuming…

The most successful Google applications serve such a utilitarian mandate, too: they encourage users to search for something, consume, and move onto the next thing. Get in, do your business, get out…

Facebook is a lobster trap and your friends are the bait. On social networks we are all lobsters, and lobsters just wanna have fun. Every time a friend shares a status, a link, a like, a comment, or a photo, Facebook has more bait to lure me back.

Which kind of user are you when it comes to health information? How has it changed under different circumstances? If you develop health apps online, are you aiming for pandas or lobsters? Is it possible to do both?

I’ve started my own list of panda health apps vs. lobster health apps — if certain sites and apps pop into your head, please share them in the comments.

Great points….What about those motivated patients whose condition cannot be addressed (or minimally addressed) by either behaviour change or there is no best known therapy….where are we on the chart?

Oof. Great question – let’s see if you and I can find some people to help answer it.

There is almost always a behavior change that will improve health. For example, better diet and exercise is almost always supported. Many conditions for which there is no therapy can be worsened by comorbidities for which there are. Beyond this, keeping a log of activities and symptoms can establish patterns that were previously unknown. I’d suggest two steps: First, if your physician tells you that you are a passive victim of your condition, change physicians. There is always something that you can do to either improve outcomes or understanding. Second, engage with your physician to discuss your own observations of yourself. Physicians who work with untreatable diseases usually care to find treatments, and should be interested in finding even that one thing that makes a small difference.

Read the New Yorker article by Gawande on Cystic Fibrosis, “The Bell Curve”, to see how understanding an incurable disease has lead to advances that are almost half of what a cure would be: 50 years ago, patients with CF died in childhood, now they live to 45 or beyond. That’s at least half-way to a normal lifespan and all was done without breakthrough therapies. I am leading such an effort in Parkinson’s disease, consulting with a lot of the same people.

A lot of people talk about providing hope. I like to think in terms of providing progress. Progress can be improved health but it can also be improved understanding. With progress, hope will follow. The reverse is not true.

I ran a program managing depression on-line and in a RCT, we found that the more severely depressed a patient was, the more we could engage them in our on-line system for monitoring disease progression and therapeutic compliance. When you find a category of patients who are not “activated,” maybe you are not activating them the right way…. I used to play rugby and at the end of each season, I was injured and in pain. At first, it was hard for me to work out in the post season because of pain, but then I found that I could swim while recovering. Many conditions will similarly limit patients from doing what they are told, but if you work with them there may be other ways to engage them. We were all amazed at how well we could activate severely depressed patients!

I agree up to a point. When I used to work w/ special education kids (which covers a large spectrum of issues from gang kids to functionally autistic), it took a range of unique ways to engage each one to change their behaviour. Two kids with similar backgrounds would respond to the same thing in different ways. It would require constant creativity to find a hook to engage them to increase their ability and engage their motivation to perform positive behaviours.

I think health is different for a variety of reasons…

Motivation to find substitution behaviours to do different activities (to your point of swapping out swimming for rugby while healing) is usually high right after an injury. That is sometimes different than getting better. You are assuming you get better. What if you still did that and your body still deteriorated? How do you maintain the motivation? Especially, when you may know that little you do will make it better in the long run. That is my question, and why I think that the graph requires a third dimension.

I propose that there is a small population of individuals/ disease sets where one cannot match motivation and ability to outcomes. Most of the conversation around healthcare is about the big quantifiable diseases where actions requiring motivation can make a difference. And, the healthcare conversation should be about the big diseases because they are the most consuming by $$ and population.

There is a small population for which those two qualities do not quite fit. And, it is not about simply reinforcing motivation through positive reinforcement. So much of the conversation about disease management is about what we can quantify. It is the Western way. If we can quantify it we can control it.

As I go through my experience I wonder more and more about the idea that if I do all the right things it will make a difference and I can control my outcomes. Increasingly I feel I am a data point outlier.

Since my disease process began, over 16 years ago, I used to keep up on all the right research, correspond with top researchers and doctors, have the top doctors in the field, keep charts, do various adjunctive therapies, genetic testing, and joined patient groups among other things. I really believed I could overcome/manage my condition with quantifiable elements and that would make the difference. I held tight to my data, ability, and motivation. Now, I am not so sure…I am far less adamant and proactive (and am wondering if that is a bad thing). I am not suggesting that rational processes be replaced by belief, yet I am providing a counterpoint to the argument of if you can quantify it you can control the outcome. At the same token you are better off if you can quantify it. And, then I think about Malcolm Galdwell’s book, “Blink” where he essentially says our intuition knows what we need to know, and our need to quantify really reinforces what we already know.

Enough Said

More like Beautifully Said.

Your perspective is valuable and has shifted the way I think about chronic disease – not just this comment, but all that you share.

Thank you.

I love the Pandas vs. Lobsters analogy matrix, but I really don’t know what difference it makes for Dr. Joe’s model. I mean, whether your available tool is Google or ACOR, you have the tools. Also, frankly, I think the Panda tools work best when applied by Lobsters.

Also, I hate to be critical, I mean, I think you’re one damned smart lady, but I think you’re mistaken when you say that, “The element Joe is adding, which is key to health interventions, is the severity of illness (or seriousness of diagnosis).”

Fogg’s model charts motivation against ability. Joe Kvedar posits his axes as patient readiness, technological readiness, and severity of condition. Severity is motivation. The two readiness factors are, ability. What might make the Joe Kvedar model fit into the FBM is that possibility that technological readiness and patient readiness can be added to determine overall readiness. In the comments on Dr. Joe’s site, I have already suggested that patient readiness should include having selected the right provider.

I can understand that Dr. Joe wanted to highlight that both technological readiness (be it Panda tech or Lobster tech) and patient readiness are necessary elements. Possibly though, instead of considering them as separate axes, we should be considering them as additive elements in overall readiness.

Thanks for the compliment and the critique.

What I hoped to do with this post is spark new ideas for people and see if I could make visible the connections that I see between these four threads.

I’ve got a few deadlines to meet today but I’ll try to come back to explain more about why I see a difference between motivation (internally driven) and severity of diagnosis (externally driven).

If *you* have time I’d love to hear more about your vision of Panda tools in Lobster claws.

Heh. Panda tools in Lobster claws or an experienced Panda trying to crash the lobster pot party. I think I’d put ePatient Dave in one of those categories. Dave is a typical determined nerd (takes one to know one). You can see it in the Pandaish way Dave worked on his illness. He started out plugging away at the bamboo like any other hungry Panda, stripping away those rare edibles. Then, along comes Dr. Sands and hands him a prescription for a Lobster suit (URL for ACOR). So, Dave joins ACOR, but he’s still working like a Panda when it comes to evaluating data, but he gets it through the community–Lobsters passing the onion dip.

Ew!!

Interesting, on many levels.

I tend to be more of a panda than a lobster … and [so] discovered that Figure 5.3: the Chronic Quadrangle, from the Innovator’s Prescription can be viewed via Google Books.

Pete’s comment about what I might call underengagement (a la underemployment), leads me to wonder about the impact of this quadrangle. How much we really know about the influence of behavior change on various diseases? Tim O’Reilly’s evocative image of vending machine government comes up again and again for me in different realms, and I think that a more activist – or activated – approach serves us more effectively in every sphere of life and work.

Speaking of work, I’m reminded of Gallup Management Organization’s annual poll on employee engagement. As I recently noted in a post on situational dissatisfaction vs. active disengagement with jobs, the most recent Gallup poll showed only 28% of U.S. workers are engaged in (vs. disengaged or actively disengaged from) their work, and yet a recent Conference Board survey reports that 45.3% of U.S. workers are satisfied with their jobs … so a non-trivial proportion of the U.S. workforce appears to be satisfied with being disengaged from their work.

I don’t to draw too strong an analogy here, but I suspect that perceptions of being able to make an impact and the perceptions of the importance of that impact affect our motivations to be active in our work and health care practices.

Finally (for now), I recently started reading E.F. Schumacher’s classic, Small is Beautiful, and finished the chapter on Technology with a Human Face last night. I suspect that how one defines technology – e.g., technologies to support mass production vs. production by the masses – is an important factor in assessing the influence (and potential influence) of technology on the treatment of health care issues.

I’d rather not be a panda or a lobster. A panda consumes but doesn’t digest all that much (at least in this metaphor) and a lobster just a party crustacean. Unless the patients, er pandas can take the bamboo and build something with it. I think health info websites/apps could benefit from more thought about behaviors they want to trigger and design around that vs just porting content with pretty content and flash and a few discussion forums.