There are several stages in becoming an empowered, engaged, activated patient – a capable, responsible partner in getting good care for yourself, your family, whoever you’re caring for. One ingredient is to know what to expect, so you can tell when things seem right and when they don’t.

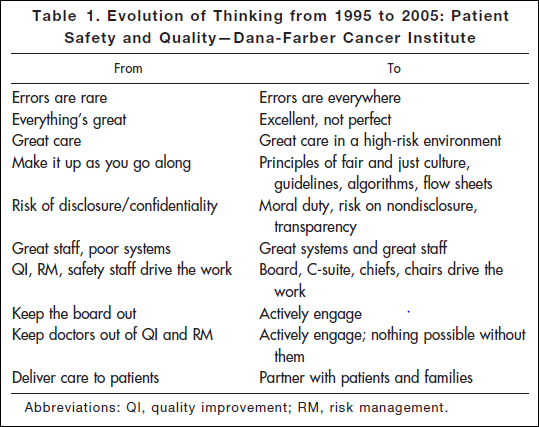

Researching a project today, I came across an article published in 2006: Key Learning from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s 10-Year Patient Safety Journey.* This table shows the attitude you’ll find in an organization that has realized the challenges of medicine and is dealing with them realistically:

“Errors are everywhere.” “Great care in a high-risk environment.” What kind of attitude is that??

It’s accurate.

This work began after the death of Boston Globe health columnist Betsy Lehman. Long-time Bostonians will recall that she was killed in 1994 by an accidental overdose of chemo at Dana Farber. It shocked us to realize that a savvy patient like her, in one of the best places in the world, could be killed by such an accident. But she was.

Five years later the Institute of Medicine’s report To Err is Human documented that such errors are in fact common – 44,000 to 98,000 a year. It hasn’t gotten better: last November the US Inspector General released new findings that 15,000 Medicare patients are killed in US hospitals every month. That’s one every three minutes.

A truth: it’s dangerous to cut people open or put chemicals in them. Deny it and you’ll have plenty of accidents. Dana Farber got to work, and their thinking evolved from the ostrich-like “Everything’s great” to the more accurate “Excellent, not perfect”; from the ostrich-like “Errors are rare” to “Errors are everywhere” and “Great care in a high-risk environment.” A key realization:

Oncology systems are too complex to expect merely extraordinary people to perform perfectly 100% of the time. Leadership has a responsibility to put in place systems and the concomitant resources to support safe practice and to mitigate the chances of error reaching patients and causing harm.

Yes, like it or not, most providers today (doctors, nurses, staff) don’t have good error prevention systems in place – they’re working without a net, and many don’t even realize it. Heaven knows why it’s taking so long to fix this; all I know is that you can be a voice for change, at the point where it matters most to you: the care delivered to your family.

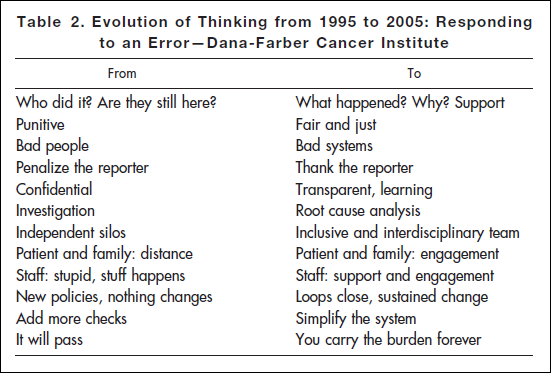

Time has shown you won’t solve this by beating on people – in fact it denies what that quote says. (How often do you improve when you’re beaten?) Dana Farber’s response to errors evolved, leading successfully to improvements:

Look, nobody likes to realize that a patient is killed every three minutes in the US. (And that’s just Medicare.) That makes it hard to work on solutions. But you really, really want providers who are working on it.

Participatory medicine can help. It’s an empowered partnership: we need to act as partners, and we need to expect our providers to treat us as partners. If they’re not treating you that way, ask them to. And if they won’t, think about leaving. You really don’t want medical professionals who are arrogant about excellence and in denial about risk, and you don’t want to be in denial, either. Be a responsible partner.

It’s best if you get that straight before a crisis hits. Have a talk with your providers; look for this approach. They may be surprised – work with them.

*Conway, J., D. Nathan, E. Benz, et al. Key learning from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s ten-year patient safety journey. In Am Soc Clin Oncol 2006 Ed Book. 42nd Annual Meeting, Atlanta, GA, 2006:615-619.

Excellent and insightful post. How did you ever find those references from 1995? Amazing that this level of clear thinking predates the IOM report.

It’s unfortunate that it sometimes takes an error of this magnitude before real change is made, but it would be absolutely TRAGIC (perhaps unforgivable?) if no one learned from events like these. In that light I think Dana Farber has done a great job at making patient safety part of their organizational DNA. Table 2 illustrates that superbly.

*Disclosure: I’ve had the chance to work with Dana Farber as a vendor on 2 separate occassions. While at Actuate:performancesoft, we had the chance to collaborate on balanced scorecards. Dana Farber is currently a client of RL Solutions (for risk management software).

Please note that one of the authors of “Key learning from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s ten-year patient safety journey” is Ed Benz, longterm President of Dana Farber Cancer Center (DFCC). It shows that the issue of patient safety is really part of DFCC organizational DNA.

And I believe the lead author, Jim Conway, was in senior management, too.

In Paul Levy’s work at Beth Israel Deaconess he often noted that these initiatives require buy-in all the way up to the board, as shown in these tables. There must be buy-in from every single person who could possibly cause negative consequences to people who tell the truth. Nothing must be more important than becoming safer.

And that’s my point in this post – I think patients who want the best care need to know what to look for.

On a related note, a new study in the Archives of Surgery has been flying around Twitter this past week: surgeons are significantly more likely to have suicidal ideas than most of us. I couldn’t see the full text but an Associated Press story says it jumps to 16% after a major medical error.

I’m glad surgeons care this much, but dear lord, when you think about the years of training and work it takes to become a surgeon, is this what we want? Suicide?

I understand the feelings of regret, shame, unresolvable guilt. That’s why MITSS was formed, ten years ago, to help clinicians and well as victims cope, recover, and move on.

Last September a post here quoted this, from the Running A Hospital blog: “From a patient who had two surgical errors in ten months: “After years of suffering through our incredibly brutal tort(ure) system I finally had the chance to talk to the surgeon. The most meaningful words he spoke were the descriptions of how badly he suffered also from the event we shared in that OR. Finally I was not alone!””

The question that keeps gripping me is what could be said or done that would make any difference – would improve the odds of good the next time one of us enters the hospital? It sure won’t be denial or beatings.

Regarding Dana Farber, another thing hospitals need to keep in mind is that an error of this magnitude is remembered forever, so far better to prevent it in the first place, for more than the obvious reason. Not too long ago the subject of Dana Farber came up in a conversation with Paul Levy and I said ‘yeah, they’re the people who killed somebody outright years ago’ – and he had to correct me that they had totally changed their culture since then. Not being local to Boston, that’s all I remembered about them. They would not have been my first recommendation for health care in Boston, unfair as that may be.

Bev, as much as I usually agree with your views, I’m concerned about this one. The fear you cite – “people remember such high-profile accidents for a long time, so it hurts your reputation” – is exactly why some people advise against open, transparent discussion of what happened.

I know you’re not advising secrecy, the famous “wall of silence” that usually happens around a medical error. I’d just hope everyone focuses first and foremost on what we can do to make healthcare better.

Really interesting perspective presented by Bev MD.

What is really remarkable is that the deadly incident is really of no concern to the thousands of ACOR subscribers who are seen by DFCC doctors and the 70,000 others who read about their adventures. In fact, if you had access to all of our archives, you would see that this institution is, on the average, very highly rated by the patients who are treated there.

With so many patients connected to large numbers of other patients it would be ridiculous to promote lack of transparency around medical errors or any abnormal behavior from a hospital or a doctor. The online community members will hear about the abnormality long before it becomes public, and will have, in some cases, developed a strategy to deal with it. That is one significant aspect of participatory medicine that doesn’t involve health professionals but can, and has, saved multiple lives.

Let me use an example: Dave, imagine that while you were undergoing IL-2 treatment your doctor disappeared overnight and you were faced by a wall of silence from the hospital. It didn’t happen in Boston and not with your doc, Dave, but if it had:

Yes. We here, in our “echo chamber” of enlightened / engaged patients, know all about checking things out (at street level reality). But of course the people we know are still the pioneers, so far out ahead in behavior that most people don’t have any idea.

I wonder how we can measure this to track our progress as the years go by.

I don’t think that ACOR communities are an echo-chamber. They are communities with ann intense purpose and have served over 750,000 people, a number at a totally different level than what’s happening in the #HCSM twitterverse.

I don’t think that our subscribers are pioneers in 2011. That’s the beauty of it. Large numbers of people have become quietly but with an intense determination, autonomous and strongly engaged in their care. No need for them to verbalize what they do, they just do it and in the process, many of them receive much better care than they would have otherwise. And none of them could care less about what we should call them.

I didn’t mean that ACOR members are an echo chamber … just meant that we here in the “empowered patient blogosphere” bear little resemblance to the norm out there.

When what we talk about here becomes commonplace I’ll need to find a different speech topic.:)

No, Dave, I’m not advocating secrecy – I’m advocating not killing people. (:

No, of course I am not saying we should go back to secrecy although, frankly, I believe secrecy still rules the day in many hospitals. I am simply saying that, as in any industry, a strong negative experience tends to outweigh many smaller positive experiences, therefore there should be even greater incentive for hospitals to improve processes and care. Frankly I am looking for any button to push which will work – there certainly seems to be a dearth of effective buttons.

I know you’re not advocating those things – I’m just saying that warning executives about “reputational risk” still drives some to the wrong conclusion…

Plus, beyond the lasting reputation issue, the *death* never goes away, for the victim or the family. That’s why it’s sooooo important to transform this – to not even give a moment’s thought to the reputation issue. Far more important is the 500 more Medicare patients who (according to the Inspector General) died yesterday.