In today’s Boston Globe, the cover story for the daily “G” magazine is “Record-Keeping 2.0,” by Chelsea Conaboy (@cconaboy). Subtitled “Medical care is shifting to electronic data files – but how safe is it?”, it’s a good mass-market introduction to the subject and where we sit today. If your grandmother or neighbor wonders what all the fuss is about, this is a good place to start.

This matters, because it’s a complex and important subject with a lot of half-informed whining, but Conaboy gets it right.

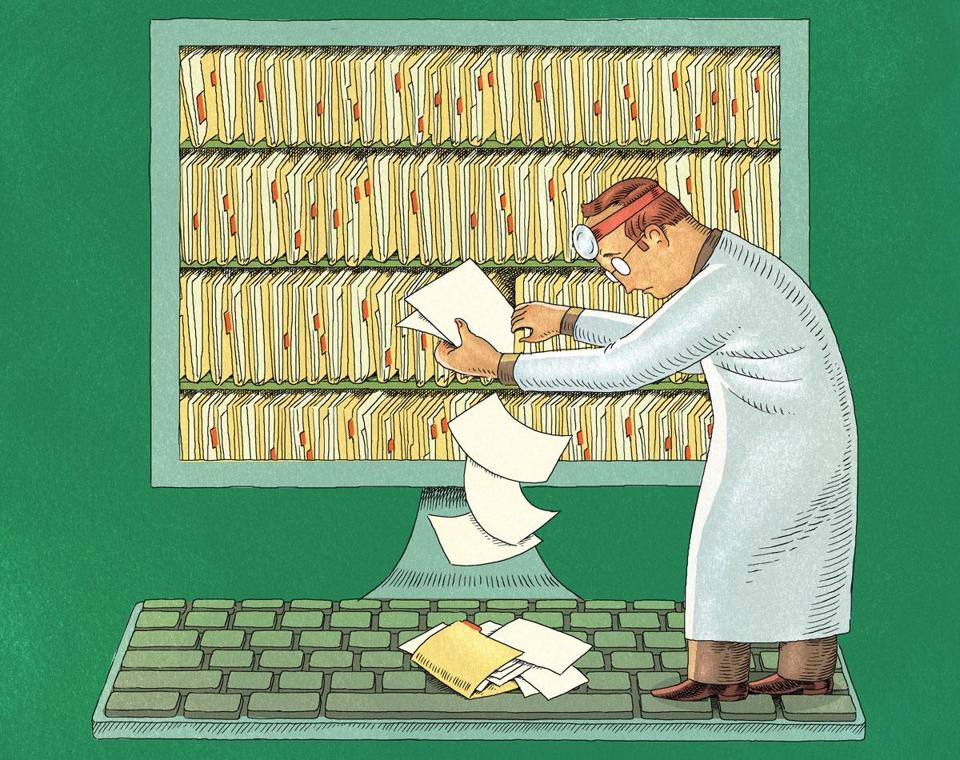

Many observers have written accurately about some aspect but have gotten the big picture wrong. Instead, Conaboy leads with an on-target vignette of a local doctor with a complex patient, focusing the story on a real-world example of why EMRs are needed: complex chronic cases like this account for a large part of America’s world-“leading” health costs.

In the vignette, the doctor’s EMR system (electronic medical record) catches a potential medication conflict. She then tours the issue as it sits today – the federal stimulus bill that’s driving adoption of EMRs, last year’s Health Affairs coverage, and the controversy created last year by Dr. Danny McCormick’s much-criticized study that, in the end, made the point that we need to ask whether these systems are in fact good.

In the vignette, the doctor’s EMR system (electronic medical record) catches a potential medication conflict. She then tours the issue as it sits today – the federal stimulus bill that’s driving adoption of EMRs, last year’s Health Affairs coverage, and the controversy created last year by Dr. Danny McCormick’s much-criticized study that, in the end, made the point that we need to ask whether these systems are in fact good.

One way this affects patients is that some of the systems are really badly programmed – “crap,” as one hospital put it. (In 2010 we reported that a big L.A. hospital was extremely frustrated by how hard their system was to use, and even the replacement they chose was “the cream of the crap.” That’s their words, not mine.) When you or your mother or child is in the hospital, do you want your doctors and nurses to be stuck with a system like that?

In 2010, while the regulations were being debated on what the government would require of these systems, it was widely rumored that a powerful EMR executive refused to allow system usability to be a criterion, saying that would happen “over my dead body.” Nice.

Not.

I made that the title of a speech I gave that June: “Over My Dead Body: Why Reliable Systems Matter to Patients.” (Slides here; see slides 48-55. Video here; this segment starts at 34:10.) But the vendor won: the resulting federal rules have no requirement that the systems be reliable or easy to use. So yes: safety is an issue that the public should be aware of.

Data quality is just as important, and not at all guaranteed: long-time readers will recall that three years ago my own medical record was discussed in a page 1 story in the Globe, because of a post on e-patients.net that discussed the many errors I found in my hospital’s insurance records. (A piece of software had foolishly assumed my insurance records would be a realistic picture of my medical history.)

Within weeks this led to the first invitations for SPM members to participate in policy meetings in Washington as the voice of the patient. I’m told that the testimony provided by several of us ended up as decisive voices for the Meaningful Use rules that require “patient and family engagement” – we the patients must be allowed to view our records, online … and report errors, and get them corrected.

This work continues, and it’ll be really, really important for patients to work together with their clinicians and vendors to get these systems to the level they need to achieve: safe, accurate, and easy to use. Conaboy’s article doesn’t specifically address the role of the patient, but it’s solid in everything it does cover, and on target.

The abundance of hard-to-use software is the only issue that repeatedly gives me reason to reconsider my decision to leave the programming field.

Here’s my take on the origin of the problem:

In order to develop software with good (much less excellent) usability, the design process must include collecting data about day-to-day operations in the context where the software will be used. That rarely happens. Instead, the standard process is to meet with a ‘customer’ and discuss their requirements. Often, the ‘customer’ in that meeting is a management-level company representative with little personal experience with the nitty-gritty of those day-to-day operations and who will seldom (if ever) use the software that’s being developed.

It’s a poor substitute, at best, and leads to a functional but hard to use end-product. At best, the result is “cream of the crap.”

An better approach would borrow an number of methods, including participant observation, from cultural anthropology to gather data about how information is obtained, used, and communicated in day-to-day operations.

For EMR software, this would mean data collection in in various healthcare facilities. It would require following staff to observe information flow; perhaps even hands-on experience working in an information-saturated non-clinical role.

The executive rumored to have scoffed at the idea of usability as a criterion probably understood this—specifically, he probably understood the kind of time and resources (i.e. money) necessary to develop software specifications the right way. That is, he understood that it would cut into his bottom line more than he was willing to accept.

After all, the only thing with such amazing ability to trump common sense is concern for one’s own wallet.

[A version of my comment (with link to this post) also appears on my blog at http://adhdgiraffe.blogspot.com/%5D