In our Society for Participatory Medicine we define this new approach to medicine as

…a movement in which networked patients shift from being mere passengers to active drivers of their care, and providers encourage and value them as full partners.

An article in today’s New York Times, Getting Lost in the Labyrinth of Medical Bills, illustrates that (at least in America) consumer engagement is important on the financial side, not just in the medical episode … because a lot of people who are running this stuff have created a mismanaged, tangled, screwed-up and incompetent mess, and we the consumers must take things into our own hands, or die at their hands. (Financially.)

I know those are strong words but I ask you to read that Times article and come to any other conclusion than “incompetent” and “mismanaged.” (I assume it’s not willful corruption.) Those words seem reasonable when providers send charges for things that didn’t happen, claim that they have no ability to control the process, and can’t help you understand what the bill should have been.

And then they throw their hands up and say costs are high because patients are irresponsible.

See what you think. First, a bit of background.

Previous posts on this site

Last September, in Design and Create a Safe, Decent, Patient-centered Healthcare System, we noted two things.

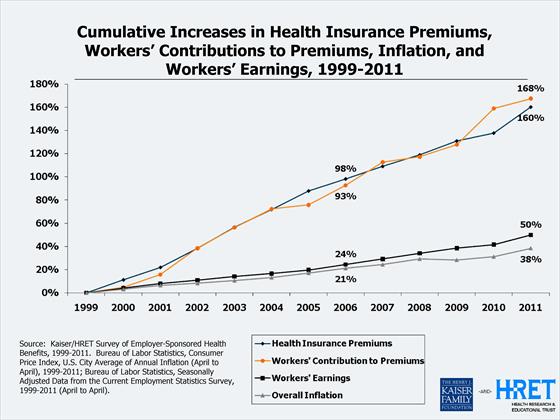

- Here’s the history of US healthcare costs since 1999. The lower lines are wages and inflation; the top lines are the cost of healthcare and (highest line) workers’ share of the payments:

Any competent business observer looks at something like this and asks, “How are these guys getting away with this?? Consumers sure aren’t reporting higher satisfaction with the ‘product’ – what’s going on here??”

Any competent business observer looks at something like this and asks, “How are these guys getting away with this?? Consumers sure aren’t reporting higher satisfaction with the ‘product’ – what’s going on here??”

Then the September post mentioned the Patient Engagement Framework created by Jessie Gruman’s Center for Advancing Health. Jessie’s team identified 43 behaviors that engaged patients must do, and grouped them into ten categories, ranging from “Find safe, decent care” to “Plan for the end of life.” I proposed an 11th category:

Design and create a safe, decent, patient centered healthcare system.

- In March, What happens when an engaged consumer tries to help control costs? described my own efforts, under high deductible insurance, to be responsible for my care decisions and their costs.

Again, the theme here is patients trying to be responsible for their health, through the medium of the care they receive. And its cost, of course. Here’s the world such consumers live in:

Today’s Times article

I wish I could paste in the whole text of today’s article, Getting Lost in the Labyrinth of Medical Bills, but that wouldn’t be legal. Please go read the whole thing, if you can – it’s just 1500 words. A few points:

- Medical billing advocate Jean Poole relates the “bewildering world of medical bills and insurance claims.” $9550 for a chemo treatment that never happened, $11,000 for 11 minute hand surgery, etc.

- “The charges have no rhyme or reason at all,” Gerard Anderson, director of the Center for Hospital Finance and Management at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “Why is 30 minutes in the operating room $2,000 and not $1,500? There is absolutely no basis for setting that charge. It is not based upon the cost, and it’s not based upon the market forces, other than the whim of the C.F.O. of the hospital.”

- … those charges don’t really have any connection to what a hospital or medical provider will accept for payment, either. “If you line up five patients in their beds and they all … get the same exact medication and services, if they have insurance or if they don’t have insurance, the hospital will get five different reimbursements, and none of it is based on cost,” said Holly Wallack, a medical billing advocate in Miami Beach.

- ” insurers can place hospitals or providers on a preferred list, which may help bolster their business, in exchange for a lower reimbursement rate.” (Yes, the hospital your insurer “recommends” can be based solely on the fact that the provider gives the company a better deal.) (I’m guessing this explains why health insurance profits are so high, while we suffer.)

- “With so little pricing information available, expecting people to shop around for quality care at the lowest cost … is sking a lot of consumers.”

- Respected health economist Uwe Reinhardt says ““I have always found a bit cruel the much-mouthed suggestion that patients should have ‘more skin in the game’ and ‘shop around for cost-effective health care’ .. when patients have so little information easily available on prices and quality.”

- Advocate Poole’s case (the example at top) found “charges for brand medications when the patient ordered generic, services that were double-billed, as well as charges for a private room that the patient did not request; he was only there because no other rooms were available. In another instance, a surgeon belatedly submitted his $4,400 bill to the insurance company, so the claim was denied. That wasn’t the patient’s fault, but he was billed anyway.”

There’s more, but all this is entirely consistent with my personal experience, going back to when my hospital sent my insurance history to Google Health (instead of my clinical history, which I’d asked for). They’d submitted billing codes for conditions I never had (blog post), like:

- aortic aneurysm

- volvulus of the intestine

- bone & cartilage disease (on a day when I only had my tongue examined!)

- intestinal parasitism (during that same tongue exam)

- pathological fracture of the vertebrae (billed in 2007 and again in 2009!)

- history of stroke

Conclusion

At the top I said these parts of our healthcare system seem to be a “mismanaged, tangled, screwed-up and incompetent mess.” I said those are strong words, but see what you think.

What do you think?

Here’s a hint: if a system’s well managed and competent, you can find someone who knows what’s going on, what it will cost, how to fix mistakes. I’ll welcome any pointers to who that is – really, I will. My insurance company, for one, doesn’t know.

___________

Epilog: the outcome of my own cost efforts

After three months of spare-time research, I reached the point where I was willing to decide and get on with life. The process was a nightmare, but ultimately I got an expected $7,000 of services (skin cancer removal and a CT scan) for about $1,000.

Wouldn’t you like to see the cost graph whacked down like that?

Wouldn’t you like to see the cost graph whacked down like that?

In thanks (not) for this effort to control costs, I got a letter this week saying that my insurance premium is going up 20%.

Twenty percent.

Post-epilog – a question to ponder:

If U.S. insurance companies are keen to control costs,

why aren’t they doing something about this?

Why aren’t their fraud departments all over things like charges for services that were not actually rendered? If false charges were on an employee’s hotel bill, would they approve it?

Do they audit 1% or 0.1% of all bills, to make sure the charges are all valid?

My insurance billing story was on the front page of the Boston Globe (April 13, 2009) – as an I.T. story, not insurance fraud, and as far as I know, the insurance company never launched an investigation. Yet every year the industry says they have to raise premiums again – because “costs keep going up.”

Last fall I complained to my insurer (blog post) that a recent “explanation of benefits” didn’t say what I was being charged for (every line item just said “Hospital”). My insurance company said they don’t know, either!

I’m not making that up! It seems that info is only in the hands of a “TPA,” third party administrator, which strips off the identifying details before sending it to my insurance company, which sends the undocumented “EOB” to me – and demands that I pay. Meanwhile, I’m not allowed to talk to the TPA.

I said this makes it impossible for me to find out if there’s fraud, and the woman actually said: “If there were, we’d do something about it.”

And yes, she said that after saying they don’t know what each line item is for.

I bet Jean Poole and her peers would gladly sell them how to audit a bill. Might save them a lot of money!

(If you’re an insurance company that does audit for fraud, please tell us about it.)

As I said before, in these matters I’m grateful for not being an American….

I can only relate what happened to me (also with high deductible self pay insurance) back in 2005. I questioned a bill for an office visit and the billing office referred my letter (non-threatening, just asking for full info) to the medical director of the clinic (about 50 docs there) and my primary care provider there sent me a certified letter that I could pick up my records and I needed to find a new provider. That is, they FIRED me as a patient for daring to ask about a bill. Welcome to the world of corporate medicine…

Oh don’t get me started. This is the bain of my existence on top of dealing with health issues. And, to me one of the biggest needs for healthcare reform, which no one is really able to tackle.