Last summer I visited Health Literacy Missouri, and summed up the great work I saw there in Clarity is Power. Today’s Boston Globe has another example – the illustration at right, what’s known as a decision aid, to help patients engage in making decisions about their medical care. “Do I want this? Is it necessary? What will we do with the answer?”

Last summer I visited Health Literacy Missouri, and summed up the great work I saw there in Clarity is Power. Today’s Boston Globe has another example – the illustration at right, what’s known as a decision aid, to help patients engage in making decisions about their medical care. “Do I want this? Is it necessary? What will we do with the answer?”

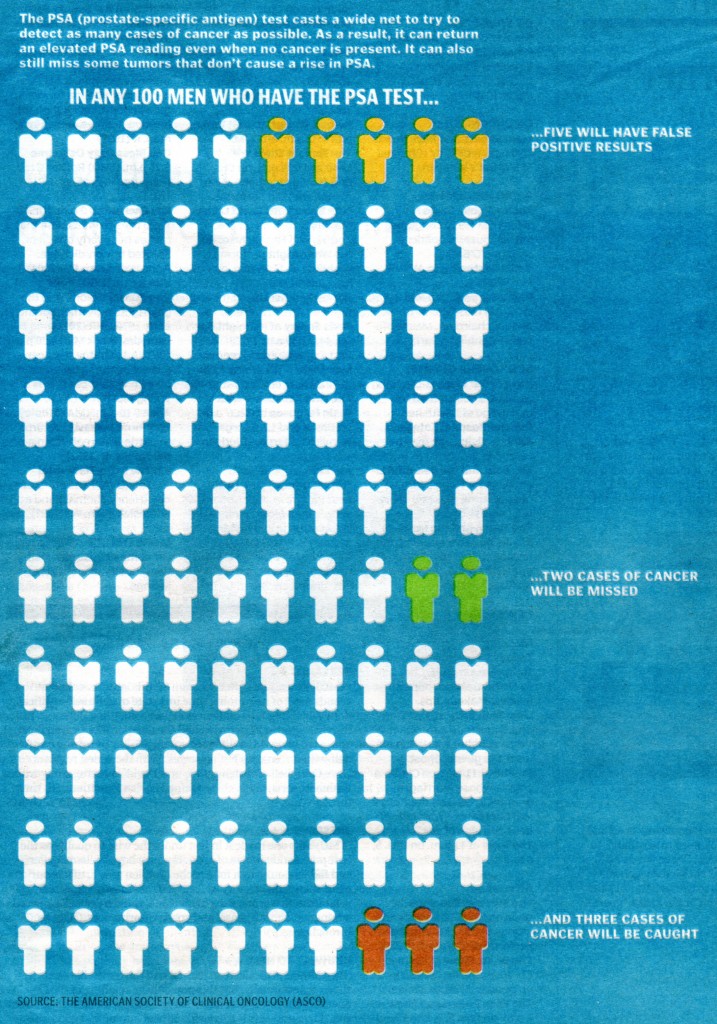

Before you read this text, read the graphic at right. Click to enlarge, if you want. Its message is pretty clear, right? It’s nifty: it clearly illustrates a situation that’s complicated. That’s valuable.

See, PSA screening is intended to detect prostate cancer, but it doesn’t work well. Anyone who follows health policy has heard the debates, sometimes crazy, about whether men over 50 should get tested. Most citizens want to do anything they can to detect cancer early and get it treated, so the natural instinct is “Heck yes, get tested!”

But it’s not that simple. The test is not precise, and regardless of the result you get, there’s the question of “What do you do about it?”

- A positive test (positive as in “bad news”) does not mean cancer. It just means a particular chemical is elevated.

- Sometimes that chemical signals cancer; sometimes it doesn’t.

- If you get treated for cancer when you don’t have it, it’s a whole lot of money and surgical risk for no benefit. (1.5% of all Medicare patients die accidentally during their hospitalization!)

- In the case of prostate surgery, your sex life might end and you might need to wear diapers forever.

- So, if the test comes back positive, do you want the surgery?

- Even if it comes back negative (normal level of that chemical), you still might have cancer.

- So, even if you do get tested, you still might not catch it.

- To put that in context, imagine looking before entering traffic, seeing nothing, and still getting hit by a truck.

I could go on and on – and the literature about PSA testing does go on and on. But a simple chart like this gets the message across quickly and clearly. And that’s empowering to the engaged patient: clarity is power.

Note to researchers: your job’s not done until people get it.

As America moves forward with Accountable Care, stakeholders everywhere will become more concerned with what works and what’s worth the cost. That’s a good thing, because too much of American healthcare has involved getting paid regardless of what works. It’s exactly like getting paid to change a tire even if the new one is still flat.

Opportunity: one of the key gaps I’ve seen in my travels is that too often truly smart people think that if they’ve said what they found, their job is done – whether or not their audience understands.

Researchers, please: “publish or perish” may suggest your job’s done when you’ve published, but that’s the difference between science and engineering: until the new knowledge you’ve generated is in use in the field, it has no impact. Please give thought to how your discoveries will roll out and reach families. There’s a hunger for more knowledge – especially knowledge that’s easy to understand. Help patients help heal healthcare.

Dave:

This is a message that cannot get enough airtime.

I have been beating this drum for years and as recently as last week (and again this morning) I had tweeted the following:

NEW RULE: The job of medical education DOES NOT STOP once content is developed, we must support the process of learning/application!

Infographics are great and they seem to have attracted the broadest attention, but it is just a start. I would go one step further: not only should information be visually intuitive and effective, but we must then support how the message is received, recorded, recalled, and redistributed.

The 4R’s are what I have come to define as ‘content architecture’ and it is an area of education (and messaging) that is woefully under-appreciated.

Thanks for the great post!

Brian

The resources offered through healthliteracymissouri.org are incredible, and are compiled for ready use by any organization. Living in So. Cal, with our mix of languages and cultures, I am acutely aware of the additional challenges the non-English have dealing with this. Just to be certain that medications are explained properly can have life-long impacts for the families and the larger community. The challenge is not to find such support, but how to implement it into a system, but this group is a model. Congratulations to them, and those that contributed.

Yes, in this age when computing power is everywhere and very good data graphics programs and sites are available, it’s a shame more effort isn’t put on “drawing the picture.” It would be a good career move for students with a flair for design, a good grasp of math, and an interest in health.