Anyone who has doubts about including patients’ input in research studies should talk with Kathleen Bogart, PhD.

She focuses on the social ramifications of facial paralysis, both congenital (like Moebius Syndrome) and acquired (like the often partial facial paralysis of Bell’s Palsy or Parkinson’s). She presented her research at the recent Moebius Syndrome Conference in Philadelphia and I got there early to get a good seat.

As the room filled up, past capacity, I became aware of how many children and teenagers were in the room, along with parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents. We were all there for an academic lecture, but some of us were going to be coloring.

First Dr. Bogart talked about how there are seven universal facial expressions, understood across all cultures: happiness, surprise, contempt, sadness, anger, disgust, fear. Someone’s ability to recognize – and use – those expressions helps determine their ability to navigate in the world.

She then talked about how, in research studies, people who are very expressive are rated more positively overall – observers think expressive people are happier, for example, than people who don’t smile broadly or move their hands when they talk. People with facial paralysis, however, are likely to be perceived as depressed. There were also studies showing that people with facial paralysis were actually depressed and less satisfied with life than other people. Further, researchers suspected that people with facial paralysis were less perceptive of emotion, less able to even identify those universal facial expressions because they couldn’t mimic them with their own faces.

It all sounded fishy to Dr. Bogart, even as an undergraduate. So she reviewed the literature and found that none of the studies differentiated between congenital and acquired facial paralysis. It took someone with Moebius – Dr. Bogart – to focus on the very different experiences of someone who has had their whole life to adapt vs. someone who has a sudden, later-in-life change in how they interact socially. It turns out that people with Moebius are just as happy and satisfied with life as everyone else. They are also just as likely as everyone else to be able to identify emotions on someone’s face.

It was very satisfying to watch Dr. Bogart present her own research, which has knocked down all the assumptions made by social psychologists who had never thought to ask someone with Moebius to contribute their insights. Through the Moebius Syndrome Foundation and a UK organization, Changing Faces, she includes people with congenital facial paralysis in all her studies, despites its rarity. (You can read more about her research in this New York Times story: “Seeking Emotional Clues Without Facial Cues”)

When Dr. Bogart asked a group of adults with Moebius to share some coping techniques, they answered:

- Do volunteer work. It establishes that you are capable and just like everyone else who shows up to provide service to other people. You’re not in need, you’re providing help. And people who volunteer are generally more open and nice – people you would want as friends.

- Use humor. “The M and B sounds are the hardest for us to say, so what do they call this thing we have? Moebius.”

- Express yourself through voice, gestures, touch, humor, clothing. “My voice is my face.”

- Wear a happy-face pin. One woman who did that said that people seemed to approach her differently.

Dr. Bogart did have some disheartening research results to share. She talked about a “thin slice” behavior study: test subjects were shown 20-second video clips of people with facial paralysis talking. Each subject then rated the people in each clip on a 5-point happiness scale. Perceptions still ran aground – people with facial paralysis were incorrectly rated to be unhappy, even by clinicians who treat people living with Parkinson’s. Oof. Sensitivity training for clinicians is next on Dr. Bogart’s agenda.

Then the Q&A started. It was immediately apparent that this was not going to be a standard academic Q&A. Here are my notes:

Q: A mom of a 4-year-old girl with Moebius described how her vivacious daughter doesn’t seem to know she is different from her friends. “How do I tell her without communicating that she is somehow broken?”

A: Practice positive ways for her to present her difference to peers. An audience member, a teenager, said that because of the way she was raised – to be confident – she never felt shy about her differences.

Q: A mom described how a teaching hospital “treated us like we were an exhibit.” The doctors and medical students didn’t even have the good grace to Google Moebius before they entered the room. What can we do about this? How can we stand up for our child?

A: An audience member spoke up to say that the reality is that you are the topic expert on Moebius, probably in the whole hospital. So don’t accept, necessarily, what clinicians say. You are the expert. Be ready.

Q: How do you introduce the topic of Moebius when you meet new people? People don’t ask.

A: Politeness norms dictate that people won’t ask, so you need to introduce it, maybe with humor. Dr. Bogart added that one positive aspect of Moebius is that “people always remember me.” She has turned her unique appearance into a positive – in job interviews and social situations.

Q: A man sitting next to me, with a teenager on his other side, asked how he could encourage his great-granddaughter to make more friends. As he put it, “Here she’s among like. Back home she’s the Lone Ranger.”

A: The girl spoke up for herself, saying, “Nobody wants to be any nicer than they need to be to the girl with a disability.” In her experience, there are 3 types of people:

- People who think that people with disabilities can’t do anything, that we’re fragile and in need.

- People who think we are inspirational and think we can fly to the moon if we wanted to.

- People who treat us like everyone else, who know that we’ll ask for help if we need it but otherwise we’re fine.

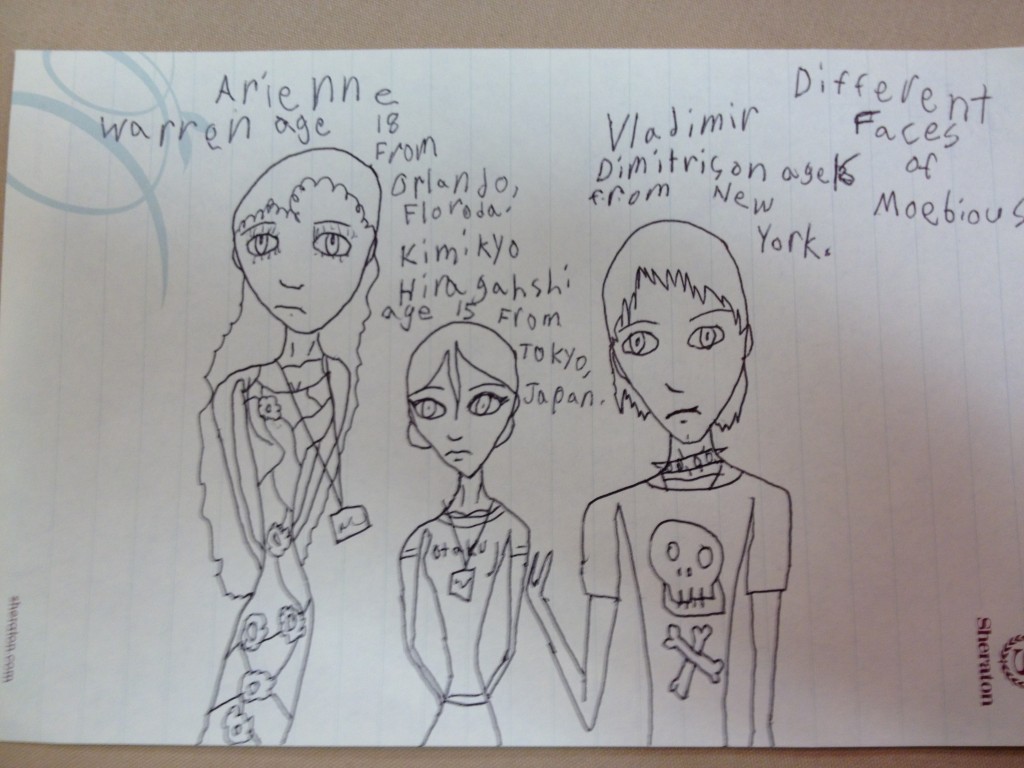

I introduced myself to the teen, Kelsey, and her great-grandfather, Gene, after the session ended. I’d noticed that she was doodling, grasping the pen with a hand that isn’t fully formed. She’s thinking about starting a comic strip about living with Moebius. I won’t tell her that she’s inspiring, but I will tell her that I can’t wait to see what she has to say, to write, and to draw next.

As an adult with Moebius I’m thrilled for any attention Moebius receives. It’s been in the dark for far too long.

Wish I could have been at the conference.

Hi Michele,

One reason I wanted to write the post is to throw a spotlight on Moebius because of its unique (and very rare) nature.

But another reason is its universality. As I listened to people with facial paralysis exchange tips about social interaction, I realized that they resonated with me, too – someone who has no FP whatsoever. My closest friends are people I met through my volunteer activities – it *can* be a filter for nice people who share your interests.

That realization was echoed over & over in the sessions. Hopefully other people will post their notes so you can share in the learning.

One must-watch video: Francis Collins, director of the NIH, serenaded the conference attendees with a lovely song on Friday

http://youtu.be/jbbW2BHMwTE

True enough, almost all smart, witty and happy acquaintances and friends I’ve been with for months tend to show a lot of expression from their faces giving you the idea of how solemn they were and honest about their shared joys and seldom sadness.

So, I’ll be honest: I can’t tell if this is a real or a spam comment.

On the one hand, taken at face value (so to speak), it addresses someone’s experience with friends’ facial expressions. Fair enough.

On the other hand, I’m so shellshocked by the sheer volume of spam comments we get that are similarly almost-but-not-quite on-point, I am suspicious. Sorry, but it’s true (and anyone who is running a blog knows what I’m talking about).

So: if you’re a real person, I’d love it if you would come back and elaborate on what you are saying. Is it that you now have a deeper appreciation for people’s facial expressions, knowing that there are smart, witty, and happy people out there who can’t make their faces reflect their feelings?

That indeed was one of my take-aways from the Moebius Syndrome Conference. One of the wittiest women I’ve met in a long time is someone who has zero facial expression. The first time she cracked a joke, I wasn’t quite sure, but started laughing. She kept talking and I kept laughing. Her facial expression had absolutely nothing to do with her wit.

I crowdsourced the “Is it spam?” question on Twitter and the verdict was unanimous: SPAM. So I edited the author to remove their link and name.

Ugh.

Side note, Susannah – I’m curious how you crowdsourced it – just asked a few folks?

I saw it when it came in and thought it was borderline but I was in a hurry. To me the two flags are quasi-coherent English (someone semi-literate trying to sound relevant to be the automated spam filters) and, of course, if the website they link to is spammy.

I tweeted a direct link to the comment and asked people to help me figure out if it is spam.

@ruraldreams @mrgunn @BethMazur @dlschermd wrote back a unanimous “yes” and we had a quick discussion about what to do. I decided to edit the author ID, but I liked Christy Collins (@ruraldreams) point: “delete – It’s like mice, let one run around, it pees everywhere, other mice smell it & think it’s a good place to be.”

Oh well.

I just want to say thank you Susannah for this post. I have an autoimmune disease called Myasthenia Gravis that causes weakness in voluntary muscles and inhibits my ability to smile.

Most people cannot begin to understand the ramifications of not being able to smile back when someone is smiling at you. It breaks a norm of unspoken communication. It is a very uncomfortable feeling, both for me and for the person I am talking with.

I loved reading about the Moebius community’s coping mechanisms! My husband thinks I should put a smile on a popsicle stick for those days when the smile just isn’t happening.

I’m just so happy to know there are so many other people like me who are ‘smiling on the inside.’

<3

Thanks, Katie!

I loved the coping mechanisms too. And I didn’t even list all of them.

I had a very interesting hallway conversation with a couple of adults who said that they feared texting and social media usage may prevent or delay Moebius teens & kids from engaging in face to face interactions. One person pointed out that she had worked very, very hard in speech therapy to be able to express herself clearly, motivated by her wish to be social the only way open to her. Now that kids have other options, will they work as hard at making conversation?

Also, if you’re interested in learning more about Kathleen Bogart’s research, definitely listen to this podcast:

http://radio.seti.org/episodes/Second_That_Emotion

I *love* the popsicle stick idea! Especially if all involved can laugh about it – I’ll start!

I’ve thought about wearing the smiley face but that’s not me so I guess I’ll just keep on just trying to convey my emotions through words & actions. I think most people that know me any at all can tell what kind of mood I’m in.

I had the pleasure of also attending this conference. What an incredible group of patients! Kelsey’s quote at the end of the session really stood out to me.

“People who think that people with disabilities can’t do anything, that we’re fragile and in need. People who think we are inspirational and think we can fly to the moon if we wanted to. People who treat us like everyone else, who know that we’ll ask for help if we need it but otherwise we’re fine.” — Kelsey, age 16.

Really informative post. For someone like myself who isn’t extremely familiar with facial paralysis, it’s very nice to come on the internet and educate myself. What an inspiring group of people.

First of all, great to see coverage of a truly unique scientific and support conference. Ok, I do not know if it is truly unique, but in conversations with scientific friends, they say they have not heard of conferences where research results are presented to and ideas brainstormed with potential research participants. Although I was unable to hear this talk, I have enjoyed several of Dr. Bogart’s presentations in the past and I am familiar with this work. Most interesting to me is the diversity of coping mechanisms that can be successful for people with facial impairments. Facial communication “hacks”? I attended the conference and have not laughed so much in a long time. Laughing, unlike smiling, is not controlled by the facial nerve…no impairment there for the people with Moebius that I have met.And I suppose I was inspired also, but no pressure, Kelsey and others!

Lol, people are talking about me in the comments! I’m such a nerd! XD

Hi Kelsey!

Nerd = powerful mind, so in that case, yes, if you want to claim that title, it’s yours :)

Let us know when you’ve got that comic strip going. We’ll feature it here!

Susannah

If Kelsey is still working on that comic, I’d love to help (for free, of course.) It looks like a good story that would do a lot of good for a lot of people :)

moncler gui 財布 クロエ 新作 http://jingdiano.gagajpdonincrease.org/

I am in such awe after reading this. My husband is an almost 20 year career Airborne Infantry Soldier. He’s deployed four times and has been jumping his whole career until year 16. High winds caused his first injury ever involving his head, helmet, and ground. After several follow ups they realized he had suffered a TBI. And since 2013 after it happened I noticed what some call a lazy or droopy eye and his cute but now crooked grin. Along with issues forming answers to simple things. I naturally felt the TBI caused the paralysis and times that simple tasks are too much. What I wouldn’t do for my husband Derek to meet you or even see you also present these conferences to various military bases and even VA Hospitals. Dr. Bogart I feel you could be the start to my husband better understand all he is dealing with. I do plan on saving this site for him to look over. But here at Fort Bragg alone you as a speaker would be better therapy, meds, etc…if only these soldiers could listen and see you break down something I can bet military hospitals and doctors do not accept as a factor into many things associated with TBI patients. I plan on reading and printing as much of your work as I can. Again I may never get to meet you nor Derek but in your time as busy as you are Could you find it in your heart to possibly email him via my provided email, and just give various not known knowledge about Moebius, and how between him possibly having this syndrome plus the TBI he may never fully regain all of himself but he can learn ways that are himself along with a new himself he’ll learn to accept.

And truly I’d love to see you do a study strictly military related, and help not only myself, plus Derek. But just maybe stubborn Army doctors and fellow soldiers too scared to address any of this or other things with anyone.

Yes again your schedule is insane I bet, but I’m sure if you came to speak over a few hours, your work and true studies you have done to show the doubters could also begin another way to things. And Derek would be so perceptive with your conferences and research. I know I’m a wife of a senior NCO not anyone big in the overall way of things. But I do know the right people who would be able to orchestrate you maybe holding a conference here. If not then as I wrote earlier sending an email to Derek just talking to him from your words on paper and that he’ll enjoy.

Again I’m just Mary, a wife madly in love with the man who also was my first love in high school. And I reaching pretty far, but I don’t actually think I am. Not if it helps our soldiers here, and their wives, and the higher ranked officers. You could possibly be a cause of a new game used to trigger their thought process, and not focus on their facial paralysis.

All in all I gotta thank that Tricare online waste to society site while trying to get an appointment 3 weeks after we’ve already been trying for roughly another 2 weeks. I terribly apologize for my lengthy and verbose comment I wrote to you. I do truly hope even if just by email you make time for Derek and all those like him. And I know you’d be happily welcomed here and room full of soldiers makes everything interesting. Thank you for all you have written and thank you in advance in case you decide to email Derek.

Safe flight and enjoy your much deserved vacation time.

Always grateful for how you helped me as well and didn’t have to.

Mary Jean Thompson

Mary, I’m so glad that my research has resonated with you and your husbands’ experience. It sounds like your husband has facial paralysis or palsy, but it would not be Moebius syndrome unless he was born with it. Moebius is congenital. However, there are lots of other ways to develop facial palsy. It could indeed be from the TBI, but it could also be Bell’s palsy or something else entirely. Here is a wonderful website that provides information and support for people with facial palsy: http://facialparalysisfoundation.org Regardless of what caused his facial palsy, the social ramifications are similar to Moebius. Unfortunately, your email was not posted, but I would like to send a message to you and your husband. Could you please contact me at my website (listed above), so I can do so? Best wishes.