This blogpost by Chuck Alston and Patrick McCabe originally appeared on the Health Affairs blog. Many thanks to SPM member Michael Millenson for alerting e-Patients.net to this piece.

It has been 22 years since David M. Eddy — the heart surgeon turned mathematician and health care economist — put the term “evidence-based” into play with a series of articles on practice guidelines for the Journal of the American Medical Association.

But as we have learned in the years since, one person’s evidence-based guideline is another person’s cookbook. For some, a sound body of evidence is fundamental to sound medical decisions. After all, as Jack Wennberg and Dartmouth researchers have pointed out for decades, if the practice of medicine varies so widely from place to place in this country, everyone can’t be right. Yet for others, evidence connotes not just “cookie-cutter medicine,” it is only one step shy of a trip to the death panel. This heavy baggage influences the way evidence-based medicine is discussed from the doctor’s office to the clinic to Capitol Hill.

With this in mind, we and others working under the aegis of the Institute of Medicine set out to find an evidence-based approach to communicate with the public about evidence. The full fruits of our work can be seen in this new IOM discussion paper, “Communicating with Patients on Health Care Evidence.” What we found based on both focus groups and a national poll is that, in the context of shared decision-making, the public does not view evidence-based medicine as an indicator of cookbook medicine. Far from it. Patients actually put significant emphasis on the latest medical evidence.

The survey of 1,068 patients conducted by Consumer Reports National Research Center this spring found that patients view evidence about what works for their condition as more important than their provider’s opinion or their personal goals and values.

But that’s not all. While they highly value evidence-based medicine, patients actually want the trifecta — all three elements to inform the decision. As the paper concludes: Each decision “is patient-specific; it depends upon the medical evidence, the providers’ clinical expertise, and the unique and individual preferences of the patient and family.”

The report draws on individual interviews and focus groups we conducted in fall 2011 with Lake Research in three U.S. cities to develop messaging to use when talking about evidence. This spring, Consumer Reports fielded the poll to quantify the attitudes, beliefs, and preferences we found in the focus groups. We also wanted to compare different ways to talk about evidence. Here’s what we found.

First and foremost, patients want more meaningful discussions with their care provider when making health care decisions. The survey found that just 6 in 10 strongly agreed that their provider listens to them, and less than half strongly agreed their provider takes the time to understand their goals and concerns. Fewer than 4 in 10 said their provider clearly explains the latest medical evidence. Additionally, less than half of people surveyed reported that their provider asks about their goals and concerns for their health and health care.

The survey also found that eight in 10 people strongly agreed that their provider should tell them the full truth about their diagnosis, no matter how unpleasant. Two-thirds strongly agreed their provider should tell them the risks of the treatment options and 65 percent wanted to hear about each option’s potential impact on quality of life. Almost half said that they want their provider to discuss the option of NOT pursuing a test or treatment, and an additional 41 percent said they “somewhat agreed” with this statement.

Again, that’s not what is happening. Only 4 in 10 strongly agreed that their provider clearly explains the latest medical evidence or that their provider explains the option of doing nothing.

To understand what people think of the role of evidence in medical decisions, we asked them to rate the importance of 1) the providers’ clinical expertise, 2) medical evidence, and 3) their own preferences and goals. We found strong support for all three. Patients valued evidence about what works for their condition more (71 percent rated it very important) than both their provider’s opinion (61 percent) and their personal preferences (57 percent). The differences are significant but narrow, suggesting the three parts stand well together.

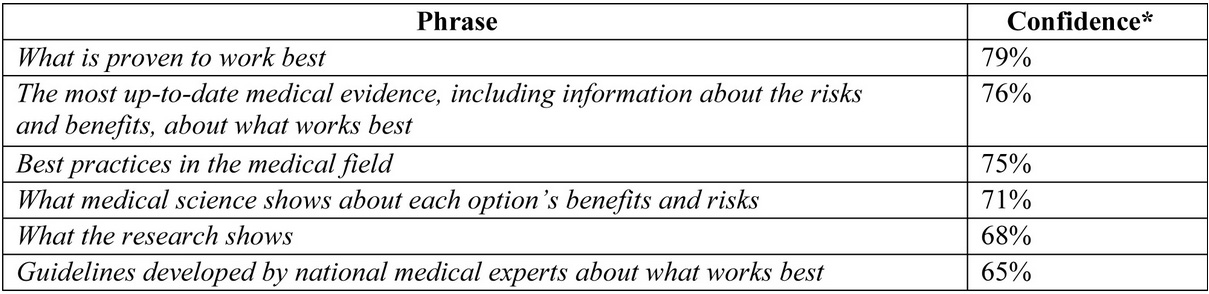

To determine the specific language that can be used to communicate about medical evidence, we asked people how confident they were that a particular phrase described the information they need to make decisions about treatments with their provider. Guidelines, research, best practices all paled beside the short and sweet phrase “what is proven to work best.”

(* Differences of 3 percent are significant at a 95 percent confidence level.)

Finally, given that rating hospitals and clinicians on their patients’ experiences is front and center in health care today, it is worth noting this finding, even if it is intuitive: People who are more engaged in health care report a better experience. We found that patients whose providers listen to them, elicit their goals and concerns, and explain their options, among other things, are three to five times more satisfied with their providers.

None of what we found will happen if a rushed doctor is reaching for the door knob a minute after a visit begins. But even if we make it easier for doctors to do the right thing, they first need to understand that engaging patients in a shared, informed, evidenced-based decision is the right thing to do. The evidence is in.

Note: This work was conducted by participants in the Institute of Medicine’s Evidence Communication Innovation Collaborative (ECIC), a project of the Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care. The Collaborative’s charge is to accelerate the routine use of the best available evidence in medical decision-making by raising awareness of and increasing demand for medical evidence among patients, providers, health care organizations, and policymakers. Its ranks include doctors, nurses, communication experts, decision scientists, patient advocates, health system leaders, and more.

Editor’s Note: The October Health Affairs issue, titled “Current Challenges In Comparative Effectiveness Research,” will address the question of how best to communicate the results of that research to patients and others. The issue will be released at 4:00 PM ET on Tuesday, October 9, and a briefing on the issue will be held on Thursday, October 11. Watch this blog for more on the October issue and the briefing.

–Excellent post Kathleen! Modern, Western patients live in a capitalistic world flooded with consumer products designed to serve their every need. It is no surprise that modern patients have grown to view medical care as yet another consumer good that ought to be customizable, substitutable, and personally satisfying. This post and the information supplied by the cited survey illustrate how modern patients commoditize biomedicine through their desire for personalized medicine, multiple treatment options, and personal satisfaction.

–Firstly, modern patients want personalized medicine. However, this does not necessarily mean that patients want the most effective medical care, but rather, treatment that best suits their individual physiological needs and personal preferences, a “patient-specific” diagnosis. The survey’s note of patients’ high regard for evidence-based medicine reveals modern patients’ desire to utilize evidenced-based medicine to achieve their ultimate goal of personalized medicine. Additionally, modern patients wish to obtain a comprehensive, customized diagnosis, based on “medical evidence, the providers’ clinical expertise, and the unique and individual preferences of the patient and family.” This furthers the notion that patients no longer value doctors and medical research independently, but rather wish to explore how these sources of information can be combined to create their unique medical treatment. Much like how a child desires a monogrammed backpack, modern patients desire medical care designed to fit their individual preferences.

–Just as one might “shop around” for competing products before purchasing one, modern patients wish to consider multiple options in their selection of a medical treatment, as indicated by the survey. Patients no longer wholeheartedly agree with the findings and recommendations of doctors and researchers. In fact, patients question the need for biomedicine. The survey reports that half of modern patients want their doctor to discuss the option of not pursing a medical test or treatment, indicative of the loss of value for biomedicine and preference for alternatives in medical treatment, among modern patients. Furthermore, in the modern patients’ pursuit of what the post describes as “what is proven to work best,” patients have turned to other patients. Through the Internet and online blogs, patients communicate with patients facing similar health problems to identify possible alternative treatments to serve their medical needs.

–Finally, the value placed upon of patient satisfaction with medical care, independent of health outcomes, has furthered the commoditization of biomedicine. As noted in the post, Consumer Reports National Research Center conducted the study, suggesting that not only is health care a consumer good, but can also be accurately evaluated through the means employed by a product reviewing organization. A patients’ satisfaction with their medical care is based upon numerous factors, including their perception of the medical care they receive and their interaction with their health care provider. The post further notes that hospitals and clinicians are rated based upon their patients’ satisfaction, as opposed to success in achieving desired health outcomes. The importance of patient satisfaction in medicine illustrates the modern patient’s treatment of medicine as a consumer good.