USA Today has a piece today on HealthGrades, one of the sites that provide information on medical outcomes and safety. The data show that quality varies widely. Experienced e-patients know this, and will learn what they can about their local treatment options.

USA Today has a piece today on HealthGrades, one of the sites that provide information on medical outcomes and safety. The data show that quality varies widely. Experienced e-patients know this, and will learn what they can about their local treatment options.

e-Patients, the time to learn about this is before you have a crisis. As we reported last year, Jesse Gruman’s patient engagement framework lists ten categories of engagement behaviors, and #1 on the list is:

- Find Safe, Decent Care

There are no easy answers here – no hospital is great at everything. Medical care is complicated, with many variables: it’s not like an auto production line where you figure out all the variables and “just do everything right” – many many tasks get done, by a wide range of people under highly varying circumstances. So if you choose to be proactive in selecting a provider, find out about the hospital’s overall record, but also look into the specific procedure.

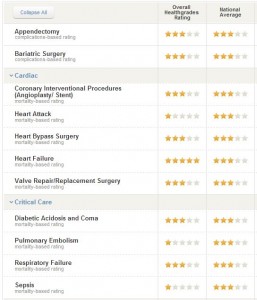

Example: above is a sample of ratings at one hospital in the Boston area. Note that the patient outcomes vary widely even within a specialty. (Some providers always argue with ratings, but the article quotes George Halvorson, widely respected chairman of Kaiser Foundation Hospitals: “You can’t make progress without ratings.” So if you want to be responsible for your care, learn what you can, even while you realize that the data’s not perfect.)

Reputation is no sure predictor of outcomes. While writing this I browsed a number of hospitals, local to me and big-name hospitals nationwide, and man is there variation. Word of mouth can be useful, but it doesn’t correlate with the data, so you should know what you want and choose with your eyes open.

In one famous place, quality data was all over the map – 12 one-star ratings and only 2 five-stars. But that can be affected by patient mix and other factors: a top-name place draws more complicated cases, and, as the USA Today piece says,

“People come to [hospitals] far sicker if they’re from a low-income area,” Foster says. “They might have multiple complications [that have not been adequately treated]. They might struggle to find healthy food. They might find it hard to find a safe place to exercise. All are important components of good health outcomes.”

Still, that can be an excuse for shoddy work. Years ago a relative was hospitalized in an economically depressed area, which was a factor in his condition, but the hospital was severely lacking in basic competence: their ICU methods were years out of date, and he’d ended up in the ICU partly because staff had stopped feeding him, presuming he was dying. (I’m not making this up.) (The family helicoptered him out of there and he outlived his physician by a decade.)

Meanwhile, at that big-name hospital, 9 out of 10 patients would definitely recommend it to others, although every aspect of patient experience was completely average or worse! Less likely to get help when they needed it, less likely to say their room was quiet at night, etc. I guess that shows the therapeutic(?) value of having confidence in a place: people apparently felt cared for, even though objectively these numbers say it wasn’t happening better than anywhere else.

Bottom line, it’s complicated, so if you want to optimize your chances, get the information you can, don’t expect it to be perfect, and stay engaged in the case during the stay.

And run from anyone who argues that you shouldn’t. They’re either unaware of the facts (which is never good in medicine) or in denial (ditto). Participatory medicine welcomes informed, engaged conversations.

___________

Other sources of ratings:

- Consumer Reports Hospital Ratings

- The government’s Hospital Compare, which is a source of data used by many other sites

- Leapfrog Group

If you know others, let me know in a comment and I’ll add them here.

I’m explicitly excluding the highly commercialized U.S. News and World Report ratings, because they won’t publish the facts on which they base their ratings. Ignore them.

My e-patient journey started long ago, in 1973, when my grandmother was hospitalized with what was thought to be an end-of-life illness. The problem in this instance wasn’t the hospital, it was the GP in our small home town, who was beloved by all. He’d been practicing for close to 50 years, and had become a pill-pusher extraordinaire.

A quick survey of Nana’s meds revealed FORTY different pill bottles, all with different meds, most of which were interacting with each other in life-threatening ways.

Dr. [redacted] would have been getting a 5-star review from every single one of his small-town patients had online ratings been available at the time.

Caveat emptor, always. Online rating services are not all created equal, as Dave points out.

Right, Casey – I’ll add, for those who haven’t been swimming in this issue for ages, that being “liked” by patients is no indication of quality, and another example is that addicted narcotic-seeking patients REALLY like a doc who says yes to anything they want.

I know you know this too but I’ll add it for other readers:

__________

One of my rules about the interwebs is: there are a lot of different people out there and you pretty much have no idea who wrote what. So take a rating just at face value, as another piece of the never-really-certain info we can find.

And that includes, of course, drugs that were approved by the FDA and may someday be withdrawn, and all kinds of things.

The truth is that whether we like it or not, life is uncertain and that includes medicine. There would be a lot less delusion (and I suspect fewer lawsuits) if everyone agreed on that as base reality.

(As I say, I know you know that.)

And still, as Halvorson said: we gotta have ratings, we gotta have comparisons. You can’t improve what you’re not measuring.

Dave, Casey –

Unfortunately, the usefulness, reliability and validity of federal, state and commercial (e.g HealthGrades, AngiesList, etc.) physician rating sites… are suspect at best and can hardly be trusted and used to make informed, important personal choices that will affect ourselves and our loved ones.

I am passionate and dedicated to advancing the measure of patient’s experience of care and creating a public trust of insight.

The words of President, Abraham Lincoln from the famous House Divided speech ring true to this day: “If we could first know where we are and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do and how to do it.” And this was decades before Demming and Drucker.

Halvorson was right when he said: “We gotta have ratings, we gotta have comparisons. You can’t improve what you’re not measuring.”

But we have a problem that can be summed up in a quote from the classic movie Cool Hand Luke: “What we’ve got here is failure to communicate.”

Many providers across our fragmented healthcare delivery system do a fair to poor job of effectively engaging and educating people. They score poorly on our CAHPS recent visit surveys when it comes to empowering their patients. They are simply not teaching patients to self-care for themselves the other 350 days of the year, when they are not sitting for 45 – 60 minutes in the “waiting room” not knowing when they will be seen by the doctor for their 7 minute visit.

I was quite encouraged several years ago when Dr. Judy Hibbard, MPH, first introduced the Patient Activation Measure (PAM). This short and powerful assessment tool could help determine the ability level of a patient to understand what is being “told to them” by their doctor.

There’s no doubt that engaging patients to be an active part of the care process is an essential element of the quality of care.

But merely knowing your patient’s PAM score is a cliff hanger. What’s the doctor going to do then? How will she know what to say and how to say it? And with raw clinical data elements being “trapped in the EHR”, how is a doctor supposed to create an individualized patient care plan that’s meaningful and can be put to use at home where it’s most needed?

The communication conundrum is compounded by the impact of health literacy across our population, which affects 90 million people. Addressing health literacy is an essential first step and we will need to train doctors, front line nurses, care managers and coordinators, patient navigators, community based workers and others.

But to really move forward and swing the needle, we need disruptive innovations in care. And we can and are inventing.

By gaining an accurate pulse on the “typing” of patient’s behavioral psychosocial, emotive and empathic make-up… we can use those insights to drive behavioral change. Leveraging breakthrough predictive communication technology that incorporates health literacy best practices, we can equip doctors with personalized on-demand care plans they can give to each patient… guiding them in wellness and to and through recovery.

Doing so, we can enhance population health, improve patient chronic self-care management, avoid hospital readmissions and reduce risks and total cost of care.

I am optimistic on the future of healthcare in America… and appreciate your efforts to advance the cause.

Hi Mark – I agree with everything you say – it’s messy with a thousand confounding variables. And still, as we both say: we gotta start somewhere.

My personal sanity check on any ratings site (or any info site, actually) is to pick anything where I have first-hand experience and see if the site is in touch with reality.

That’s how I realized that EVERY kidney cancer website falls short of what the ACOR.org patient community knows. And it’s how I realized that this site is pretty much on target about St. Joseph’s in my town – a totally average hospital, which is not very good.

And, to illustrate the weakness of HealthGrades, consider how much more info you get from Leapfrog Group, which gives the same hospital a grade of C (where A is best), based on far more measures, which they display for you: http://hospitalsafetyscore.org/hospital-details.html?location_id=1458

That hospital doesn’t report a lot of data on their quality measures (no surprise IMO) but near bottom, see Patient Safety Indicators: “Death From Serious Treatable Complications After Surgery.” Out of every 1,000 surgical patients, 132 die of a complication that could have been treated if the patient had been managed well! 1 in 8! Seems to me their safety grade ought to be posted on the front door, and every Informed Consent form should disclose that.

And why do I say this makes sense? Because when a relative was in there in December, not a single employee who entered or left the room washed their hands. Even though the patient had C.diff.

I say, we gotta start somewhere in measuring and reporting this stuff. And smart caveats like yours are what will refine the data and its use. But we gotta start.

Healthgrades is basically a public relations agency which, for a fee , will put out and promote a high “grade” for a member institution. Caveat emptor…

Hi – are you saying their ratings can be bought and shouldn’t be trusted? (I don’t know – just asking.)

There may possibly be some thing wrong with your site links. You should have a web developer take a look at the website.

LOL – so this is what I get after pointing out that you’re a low-rent link spammer eh? :-) Have a nice life…