A guest post from the Engage with Grace team…

A guest post from the Engage with Grace team…

One of our favorite things we ever heard Steve Jobs say is… ‘If you live each day as if it was your last, someday you’ll most certainly be right.’

We love it for three reasons:

- It reminds all of us that living with intention is one of the most important things we can do.

- It reminds all of us that one day will be our last.

- It’s a great example of how Steve Jobs just made most things (even things about death – even things he was quoting) sound better.

Most of us do pretty well with the living with intention part – but the dying thing? Not so much.

And maybe that doesn’t bother us so much as individuals because heck, we’re not going to die anyway!! That’s one of those things that happens to other people….

Then one day it does – happen to someone else. But it’s someone that we love. And everything about our perspective on end of life changes.

If you haven’t personally had the experience of seeing or helping a loved one navigate the incredible complexities of terminal illness, then just ask someone who has. Chances are nearly 3 out of 4 of those stories will be bad ones – involving actions and decisions that were at odds with that person’s values. And the worst part about it? Most of this mess is unintentional – no one is deliberately trying to make anyone else suffer – it’s just that few of us are taking the time to figure out our own preferences for what we’d like when our time is near, making sure those preferences are known, and appointing someone to advocate on our behalf.

Goodness, you might be wondering, just what are we getting at and why are we keeping you from stretching out on the couch preparing your belly for onslaught?

Thanksgiving is a time for gathering, for communing, and for thinking hard together with friends and family about the things that matter. Here’s the crazy thing – in the wake of one of the most intense political seasons in recent history, one of the safest topics to debate around the table this year might just be that one last taboo: end of life planning. And you know what? It’s also one of the most important.

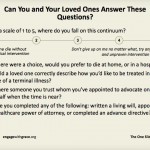

Here’s one debate nobody wants to have – deciding on behalf of a loved one how to handle tough decisions at the end of their life. And there is no greater gift you can give your loved ones than saving them from that agony. So let’s take that off the table right now, this weekend. Know what you want at the end of your life; know the preferences of your loved ones. Print out this one slide with just these five questions on it.

Have the conversation with your family. Now. Not a year from now, not when you or a loved one are diagnosed with something, not at the bedside of a mother or a father or a sibling or a life-long partner…but NOW. Have it this Thanksgiving when you are gathered together as a family, with your loved ones. Why? Because now is when it matters. This is the conversation to have when you don’t need to have it. And, believe it or not, when it’s a hypothetical conversation – you might even find it fascinating. We find sharing almost everything else about ourselves fascinating – why not this, too? And then, one day, when the real stuff happens? You’ll be ready.

Doing end of life better is important for all of us. And the good news is that for all the squeamishness we think people have around this issue, the tide is changing, and more and more people are realizing that as a country dedicated to living with great intention – we need to apply that same sense of purpose and honor to how we die.

One day, Rosa Parks refused to move her seat on a bus in Montgomery County, Alabama. Others had before. Why was this day different? Because her story tapped into a million other stories that together sparked a revolution that changed the course of history.

Each of us has a story – it has a beginning, a middle, and an end. We work so hard to design a beautiful life – spend the time to design a beautiful end, too. Know the answers to just these five questions for yourself, and for your loved ones. Commit to advocating for each other. Then pass it on. Let’s start a revolution.

Engage with Grace.

It is certainly important to discuss end-of-life, and the Engage with Grace questionnaire here is useful. It’s amazing that this subject is still something that has to be pushed out there.

However, there’s still an aspect that I’d like to discuss that isn’t in the usual end-of-life dialogue. I think all people should have the option of creating a contract for conditions under which they would be euthanized if they are unable to end their life themselves.

I live in Oregon where there is the Death with Dignity Act. The law states: “the Death with Dignity Act … allows terminally-ill Oregonians to end their lives through the voluntary self-administration of lethal medications, expressly prescribed by a physician for that purpose.” There are two big limitations in the law: the person has be judged terminally ill within 6 months, and the lethal dose has to be self-administered.

So for people with a diagnosis of dementia this law is of no help. Alzheimer’s patients can live 3 to 20 years after diagnosis. Long before death the patient will almost certainly sink into deep dementia. At that point they cannot express their desires, influence their care, nor administer any medications to themselves. Caregivers and physicians can do nothing and will do nothing except administer largely ineffective drugs.

I have had a lot of personal experience with dementia. My father had Alzheimer’s, my mother became demented after an iatrogenic stroke, and my mother-in-law has been sinking into dementia for over 10 years. I have no desire to live until death with dementia. I have made my wishes abundantly clear to my wife — the only person who will have any authority regarding my health — but there’s nothing she would be able to do.

What I think is needed until some truly effective treatment is available is a document that can be appended to the standard end-of-life DNR statement — while the person is of sound mind — that states that they do not wish to live if they drop below a defined and tested level of cognition. Research is needed to identify a series of measures that can give clear indication when cognitive decline has reached specific levels. The tests may be both brain imaging by MRI and cognitive performance testing. Perhaps the test would need to be administered a couple of times to verify results. But after the agreed upon level is confirmed, a physician would be legally empowered — indeed, required — to comply with the patient’s contracted wishes.

Thanks so much for this comment, David! I’ve been thinking about it since you posted it, but don’t have an “answer” besides “thank you.”

What she said.

This was a great article. I really think death can be our greatest motivator, without dwelling on it. I really appreciate the perspective.

David – Glad you raised this point. Public opinion on medical care still favors longevity over quality of life – and this is true in cases of cancer or Alzheimer’s. Some oncologists even admit to feeling that they’ve abandoned their patients when they cannot help them, and consequently suggest futile treatments (see NYTimes: Aiding the Doctor Who Feels Cancer’s Toll). I hate to be cliché and suggest we’re waiting for a cultural shift, but I’m afraid that’s still the core of the problem.

If /when we introduce more autonomy to end-of-life care, illnesses characterized by cognitive decline, like Alzheimer’s, will receive pushback because they open up a can of worms. What about a patient with Schizophrenia who is progressively losing touch with reality and resistant to drug treatment? At what point is this patient capable of writing such a contract?

Thank you, Susannah and others, for your replies. One of the good things I think that the baby boom generation has done is break through social barriers and bring new life options for people. You know: sex, drugs, rock-n-roll, etc. When history is written I hope that we are credited with candidly discussing areas traditionally restrained by taboos, misconceptions, and dogmatic beliefs and, thereby, extending horizons for people not only in America but worldwide.

As we approach the denouement of a generation death and dying remains one gigantic topic that sorely needs opening up. This subject is still shrouded in dread and in beliefs that are not supportive of the greater flexibility in personal freedom we have achieved in other areas.

I think one of the last things we can gift to future generations is a thorough, frank dialogue that expands the range of options we have and empowers control of the death process in ways not currently available. Frankly I’m appalled at how limited we are by law and by institutions in getting our death wishes honored. Death specification has much in common of with the challenges faced by e-patients in exerting their wishes in other areas medicine.

Meddik raises some points that need to be addressed for sure. I’m no legal expert by a long shot, but it seems to me it’s well established that we have the right to write a will and specify what we want done with all our possessions. Surely there are existing criteria for judging that a person is competent or not for those purposes. Why would competence for specifying circumstances for assisted death be much different? The key is an advanced directive with specifics for defining what to do in the situation of severe cognitive decline. Unfortunately, as far as I know, there isn’t an accepted set of measures for determining how far degeneration has gone at a particular point, and nobody seems to be working on establishing some sound measures for making a judgement.

It won’t be easy. The subject is sacrosanct and embedded in powerful institutional traditions. Bringing it to more realistic terms will provoke a lot of resistance. But we’ve encountered this before, and we know that determination can achieve a lot.