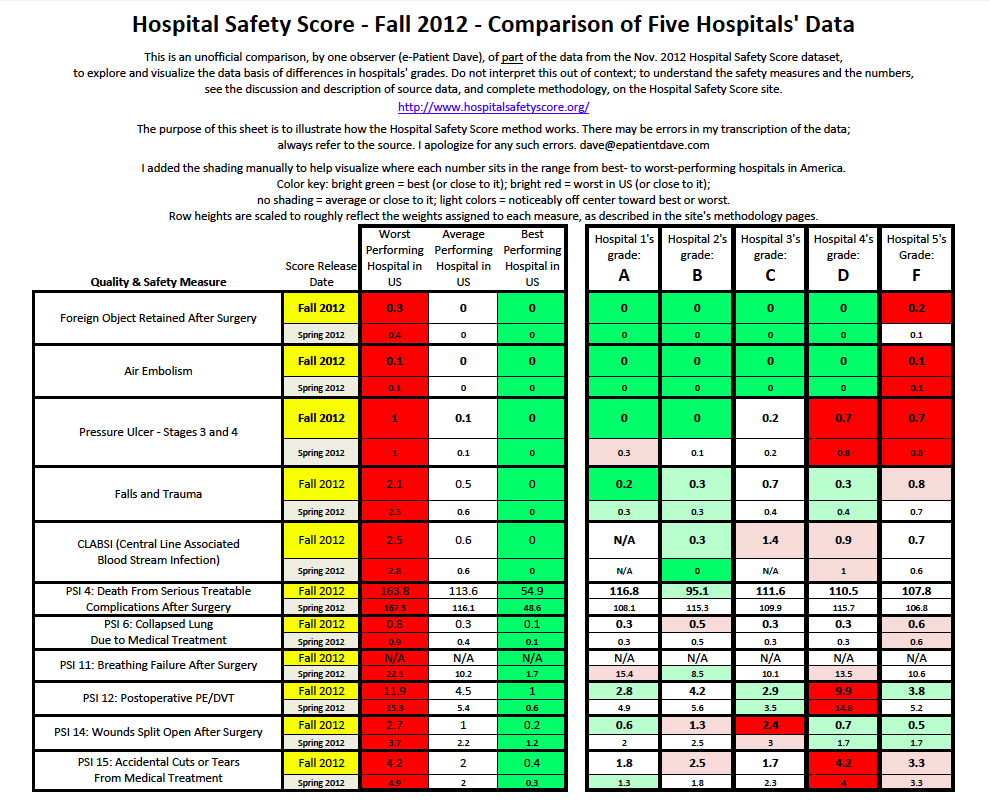

The PDF at right is a summary of sample data from this new dataset.

The Leapfrog Group is a highly respected patient safety organization. They’ve earned a reputation for carefully and thoughtfully assessing providers’ actual performance in quality and safety. Their mission statement:

To trigger giant leaps forward in the safety, quality and affordability of health care by:

- Supporting informed healthcare decisions

by those who use and pay for health care; and,- Promoting high-value health care through incentives and rewards.

Today, Leapfrog’s affiliated organization Hospital Safety Scores announced a major update of its A-through-F grades of thousands of US hospitals, and new smartphone apps to access the data on the fly.

Predictably, the hospitals who got an F – based on their own data! – are saying it’s “not a fair scoring system.” Happily, Leapfrog follows the best practices of open science: they fully disclose all their data, the methodology they used, and who designed the system. This means all buyers of care – e-patients, families, employers – can examine the data and assess claims of fairness for ourselves.

The full press release is here. I won’t take time to go into it; many others are doing so – here’s a current Google News search and blog search. Here, I want to focus on two aspects that are core to participatory medicine: understanding the data, and why this matters.

In the table above I’ve summarized (somewhat laboriously) half the data for one sample hospital at each grade level. Why only half the data? Because it was a lot of work, and my purpose is only to illustrate how their analysis works. This post is about the method, not about individual hospitals.

Anyone who wants to challenge the Hospital Safety Score conclusion must identify specifically they say is wrong with the data or the method. And, just as important, anyone who wants to use the data should understand how it works. That includes patients, families and employers who want to be engaged in improving healthcare – or selecting a hospital for their own use.

In this discussion I won’t name hospitals, because my purpose here is to discuss method.

Designed by a truly blue-ribbon panel.

Leapfrog wisely convened a blue-ribbon panel to design the methodology:

- Lucian Leape MD, revered safety figure for whom the Lucian Leape Institute is named.

- Arnold Milstein, M.D., M.P.H., Stanford University

- John Birkmeyer, M.D., University of Michigan

- Ashish Jha, M.D., M.P.H., Harvard University

- Peter Pronovost, M.D., Ph.D., F.C.C.M, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

- Patrick Romano, M.D., M.P.H., University of California, Davis

- Sara Singer, Ph.D., Harvard University

- Tim Vogus, Vanderbilt University

- Robert Wachter, M.D., University of California, San Francisco

Anyone who wants to criticize the method has to discredit the thinking of these figures.

I’ve personally met and engaged with Lucian Leape, and you gotta be pretty crazy to say he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. Same for Bob Wachter. I haven’t met the others, but they have similar reputations.

In particular, Peter Pronovost is internationally known, and in April was awarded the first American Board of Medical Specialties quality and safety award. So, in a sense, anyone criticizing Pronovost’s approach is saying this board of specialties doesn’t know what it’s doing.

Pronovost has a special place in my heart (close to it, anyway), because of this item, from the award’s press release:

Dr. Pronovost is credited with developing an acclaimed five-step checklist protocol for doctors and nurses designed to prevent deadly bloodstream infections associated with central line catheters…

During my cancer treatment I had central lines inserted four times … four months after he published his checklist in NEJM. Safety matters to me, at a gut level.

The letter grades are based on a combination (as described on their site) of data the hospitals sent CMS (Medicare and Medicaid) and Leapfrog’s own data. Unfortunately, many hospitals decline to participate in Leapfrog, usually saying that they already have to report to CMS and it’s redundant. I can only assume, then, that they feel the CMS data is good enough for people to draw conclusions. (A year ago Consumer Reports told of three big systems that dropped out.)

In the PDF you can see how a range of hospitals compare in today’s new ratings – their letter grade and the underlying data for each. Here are my takeaways and why it’s important.

There is a range of quality. Consumers need to know.

As we reported in January, famed surgeon Atul Gawande said there is “a wide gap” between the best and the worst. Lesson: it’s a mistake for a consumer to think it doesn’t matter where they go – or where they send their grandmother.

Doctors need to know, too.

Don’t assume that just because your family doctor recommended a place, it must be good. Doctors can’t function, either, without this data.

I personally know a famous doctor blogger who was unaware that a hospital he uses, in his own town, is horrific about hand-washing when he’s not around. (He learned about it because a vigilant family member told him.)

More than half of hospitals got an A or B.

Good hospitals deserve to be recognized! To improve healthcare, consumers need to know who’s doing a great job and who’s doing a good job. Give us the data.

Note that the curve isn’t arbitrarily negative: 30% got an A and 26% got a B, totalling 56% B or better. That means any hospital with a C or below is in the lower 44% of performers. In particular, a D or F was given to only 6% of hospitals; 17 out of 18 had better numbers. Look at the data.

Brand is no guarantee of quality.

In the table above, the four hospitals who got A through D are all part of the same system. And it’s a big-time world-class brand. This means informed, engaged buyers need to look at the individual “shop,” not just the brand.

The specifics can help guide family vigilance.

My doctor, SPM co-founder Dr. Danny Sands, often quotes English philosopher/scientist Sir Francis Bacon: “Knowledge is power.” Without it, we’re disempowered; with it, we can contribute.

Here’s an example: I know most families won’t travel a great distance, even if it would take them to a much safer hospital. But the data can still help: if your local hospital is pretty good but ranks poorly on bedsores (pressure ulcers), you can be aware, and help the staff keep an eye on it.

* * *

To wrap it up, I’ll return to Gawande, in his talk last January, then touch on TEDMED 2012 and 2013.

To be an informed consumer, you need data on price and quality.

In that moment I cited above, the fuller version of Gawande’s quote was:

There is a bell curve for quality – a wide gap between the best care and the worst.

There is another bell curve for costs – again, a wide gap.

Surprisingly, the two curves do not match.

And that means there is hope.

Because if the two curves did match – if the best care were the most expensive – then we would be talking about rationing.

Get that? If we know who’s doing well and we know the costs, we can improve healthcare.

But we can’t reward great performers if we don’t have the data. Knowledge is power.

This will help patients behave like consumers.

Last April, at TEDMED 2012, Quest Diagnostics Chief Medical Officer Jon Cohen MD gave a talk asking “Why don’t patients behave like consumers?” Well, Dr. Cohen, really – let’s try giving consumers the same information you get when you shop for a TV or a car.

Dr. Cohen, were you aware that when I called one of your labs this year to inquire about costs, their answer to me was “We don’t know”? Can you help your company answer that question, for the next consumer who calls?

The Role of the Patient depends on information.

As we’ve noted before, for TEDMED 2013 there’s a Great Challenges program led by TEDMED and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. And one of the Great Challenges facing medicine is The Role of the Patient.

Too often in my travels I hear people saying “Patients can’t understand this stuff,” or remarks like Quest’s last April. So I’ve taken to saying, in some speeches: “It’s a particular perversion to keep people in the dark and then mock their knowledge.”

Give us our damn data, then let’s see if we behave like consumers. Good, reliable data, with an openly published methodology.

Thank you to Leapfrog, thank you to the blue ribbon panel, and especially thanks to all the hospitals who do participate voluntarily in Leapfrog. We know you’re committed to improving quality – and that builds my confidence.

Hi Dave,

Like the lessons drawn from the Leapfrog data! I had visited the Leapfrog website last year and was impressed by the work they do!

Indeed, the table you have drawn illustrates at a glance what a patient or family member making decisions on the hospital to choose, should look for.Even if, as in our case, no such statistics are available, if you know which are the “dangers” then, it might be easier to spot them.

Well, you were the hero of my blog last week with two posts!(http://wp.me/pOEgZ-E3 and http://wp.me/pOEgZ-Er) but I think that you will have a third one this week as I would reblog and translate parts of your post above!

It’s incumbent upon us to inform ourselves as we navigate the healthcare system. However, as you point out, patients have historically not been encouraged, or even in many cases allowed, to do so. Leapfrog has given us a powerful tool. It’s now up to us to use it, and to make sure the data supporting its continual updates isn’t ever turned off.

This is a red letter day for e-patients. For ALL patients.

Thank goodness my hospital rated an A !! It’s all about accountability. Thanks for Sharing.

Care to say more, Peggy, about “It’s all about accountability”? Do you mean that’s part of the culture there?

Great article, Dave! Thanks for taking the time to explain everything and comment on it.

There are only two things where I slightly disagree with you, and since you’ve asked me on Twitter to flesh them out – here you go:

1) I think the data quality might not be as good as we hope it is – this is quality and safety data reported in routine care settings with really varying degrees of reliability. So “benchmarking” against other hospitals might not be valid. By that I mean that maybe you can’t say if one hospital with a ‘C’ is really better than one with a ‘B’. But it’s important for the hospitals to know, and it’s important to know if they improve or not.

2) I totally agree with you that the methods panel is stellar. It includes some folks whose work I truly admire. However, that shouldn’t matter at all! I think the only important thing is that the methods are appropriate – that includes what data you chose to measure, how you measure them, how you analyze them – period. It doesn’t matter who designed it. That’s the beauty of science!

Thanks much, Ben! Are there any sources or methods of quality data that you value?

Thanks for this, Dave. And thanks to Leapfrog for persevering. It’s in the best interests of all — patients, providers, payers — for this info to be made public and accessible.

But let’s not forget — quality’s not the only frontier. Cost (or price) is out there too, still buried. Thanks to visionaries like Leapfrog, and like you, Dave, and Regina and Susannah and Casey and the rest of the S4PM, cost is starting to become visible, too.

With quality and cost, we can begin to understand value. And we can also begin to get at different underlying inequities in the system.

Hats off to all involved!

As a volunteer Patient Advisor serving on the Patient Safety and Quality Professional Nursing Governance Council at my regional hospital, I asked the question, “Do these Patient Safety data you’ve collected accurately reflect our patient experience?” The answer I received from a nurse supervisor was, “No, we typically under-report. It’s more like the tip of the iceberg.” You need to understand the culture of our healthcare institutions is one of cover up and work arounds. This is why Yelp and Google reviews will tell a patient far more information than any data that was generated by an institution that is used to monitor the same institution. The patient comments on returned HCAHPS surveys rarely are properly researched and adequately addressed by an understaffed and overworked Office of Advocacy, and real fixes for the system failures cost too much for hospital administration to consider on their limited budgets. -Or else we’d see improvement in our rates of medical error, which has been identified as the 3rd most common cause of death in the US. The book A Sea of Broken Hearts discusses more on our healthcare system’s lack of accountability. So let’s be candid here: patients are fighting against an undeniable barrier to our care, an insurmountable conflict of interest: our health care is being run as a business. In order to work towards real, effective change, we must begin by understanding and acknowledging there is a systemic problem and then we must accurately define the problem. Or we will never arrive at an effective solution.

Our healthcare institutions should not be designing the metrics that they use to monitor themselves nor should they be “policing” themselves.