Survey data is a snapshot of a population, a moment captured in numbers, like vital signs: height, weight, temperature, blood pressure, etc. People build trend lines and watch for changes, shifting strategies as they make educated guesses about what’s going on. What’s holding steady? What’s spiking? What’s on the decline?

Just as a thermometer makes no judgment, the Pew Research Center provides data about the changing world around us. We don’t advocate for outcomes or recommend policies. Rather, we provide an updated record so that others can make those pronouncements and recommendations based on facts.

The latest in our health research series is being released today. Health Online 2013 finds that internet access and interest in online health resources are holding steady in the U.S. For a quick overview, read on…

What is new?

1 in 3 U.S. adults use the internet to diagnose themselves or someone else – and a clinician is more likely than not to confirm their suspicions. This is the first time we – or anyone else – has measured this in a straightforward, national survey question.

1 in 4 people looking online for health info have hit a pay wall. This is the first data I know of that begins to answer the important question: what is the public impact of closed-access journals?

We added three new health topics:

- 11% of internet users have looked online for information about how to control their health care costs.

- 14% of internet users have looked online for information about caring for an aging relative or friend.

- 16% of internet users have looked online for information about a drug they saw advertised.

(A full list of all the health topics we’ve included, 2002-10, is available here.)

What has changed?

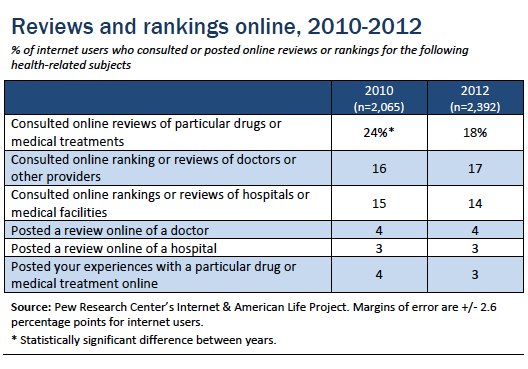

The percentage of people who have consulted online reviews of drugs and medical treatments dropped (and I don’t know why — do you have a theory? Please post a comment.)

Related: why aren’t health care review sites catching on? Pew Internet has tracked a boom in consumer reviews of other services and products — why not health care?

What to keep an eye on?

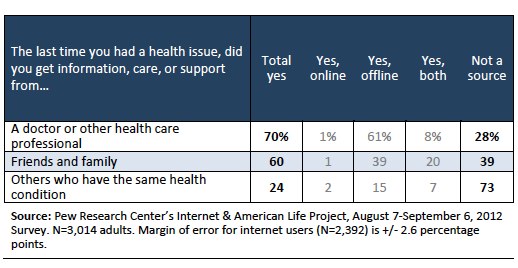

One of my favorite survey questions is asked of all adults and attempts to capture a broad portrait of health care resources that someone might tap into when they’re sick.

It’s a useful question for keeping online resources in perspective. I think it’s also going to prove useful in the coming years as the landscape shifts and people have more opportunities to connect with clinicians online. How fast will that “Yes, online” group grow? Or will care always be hands-on at its core — and therefore we should see growth in the “Yes, both” category?

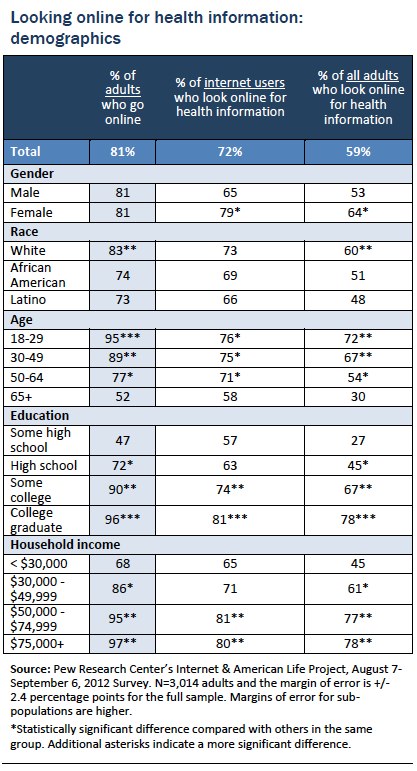

Speaking of keeping things in perspective, I think it’s important to remind ourselves that there are pockets of people who remain offline. Internet access drives information access.

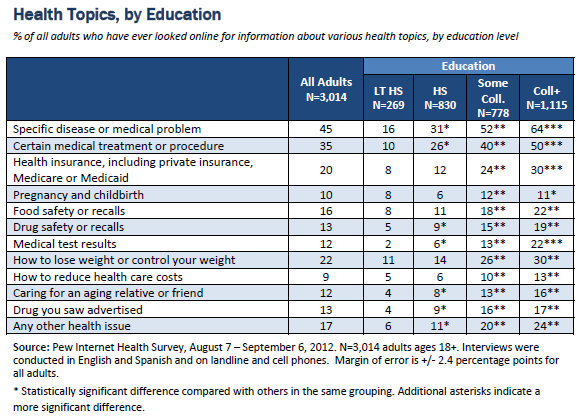

Here’s a table from the Appendix that digs even deeper:

In other words, 64% of college educated adults in the U.S. have researched a specific disease online, compared with just 16% of U.S. adults who have not completed high school.

These are just a few highlights — please read the report, ask questions, and tell us what you think: How’s the patient doing, based on this new set of vital signs? What do you prescribe?

Fascinating report, as usual!

I’m surprised that *only* 35% of US adults are ‘online diagnosers’. My initial interpretation was that 65% of US adults either do not have health problems, don’t know someone with health problems, or rely exclusively on offline resources for diagnoses.

Given that the CDC estimates that half of US adults suffer from chronic illness, and so a substantial proportion of the population either suffers from a health problem or know someone who does, it must be that many US adults are [still] not going online to search for possible diagnoses.

Another surprising finding [to me] was that only “16% of internet users say they went online in the last year to find others who might share the same health concerns”, but I’m probably unduly biased by my personal experience with a family member with several chronic illnesses. Hopefully, 84% of people don’t experience the same level of life- and lifestyle-threatening challenges that we’ve been through over the year, but given the prevalence of chronic illness, I would have thought this number would be considerably higher.

I’m sure I’m an outlier [on many dimensions], but I don’t trust any diagnoses that I cannot verify myself online … but as an academic, I have access to far more online health information than most, and unlike 26% of the survey respondents, have not been blocked by paywalls.

Thanks, Joe!

You’ve touched on a key point: this report focuses on the general population results. Later this spring we will release a special report on caregivers and then a separate report on people living with chronic conditions. These two groups do, indeed, have a different profile when it comes to internet use, particularly related to health.

In specific response to your query about possible explanations for “the percentage of people who have consulted online reviews of drugs and medical treatments dropped”, I wonder how “reviews” was interpreted by survey respondents. I was an early adopter – and promoter – of Yelp and other sites that have lots of user reviews, but over time, I have found that any sufficiently large number of signals is indistinguishable from noise.

Reputation.com, which helps individuals and organizations “manage” their online reputations, has a special practice focusing on medical professionals, and I’m sure that Big Pharma has operations with substantially more resources to “manage” the reputations of their products, among the medical establishment, general population and elected representatives.

Another possible explanatory trajectory may be related to fatigue. It seems that all kinds of conflicting studies and pronouncements come out about various drugs, tests and treatments (get a mammogram, don’t get a mammogram; get a PSA test, don’t get a PSA test). Whenever I’ve searched for information about a particular drug or treatment, I’ve found significantly bimodal distributions – mostly people who have had very positive or very negative experiences.

I can’t imagine that a growing number of people are unaware of online information available about drugs and treatments. It could be the trend is due to a growing number of people who are consciously choosing to turn off or tune out.

Fascinating questions, Joe.

Your results are always highly anticipated. Great job!

In particular, I would like to thank you for collecting data on queries related to health care costs. Although it is expected that most people will search for information on a specific medical problem, your findings show that a significant number are searching for ways to reduce the financial burden of health care.

Did the percentage surprise you?

Thank you!

We didn’t know what to expect from that question and it is our first measure of it, so I can’t say I was surprised since I had zero expectations. I also fully admit that I’m not a health policy expert. For that level of commentary, I turn to people like Jane Sarasohn-Kahn who blogged about the report this morning. One quote from her post:

“In the emerging accountable care and Health Information Exchange era, this looks like a huge challenge for consumers who need to embrace transparency and information that helps them navigate the labyrinthine U.S. health system. With the likes of Castlight Health attracting millions of dollars of venture funding, tools are being built to enable the supply side of quality and price information. But will people come? This year’s Pew health survey research reveals: not so many as will need to.”

See:

http://healthpopuli.com/2013/01/15/the-internet-as-self-diagnostic-tool-and-the-role-of-insurance-in-online-health/

Do you have previous year’s/years’ data on consulting “others who have the same condition”? I’m interested because some chronic diseases seem to attract communities — MS has several. This may reflect both age of those at diagnosis and the isolation of the disease. I’d compare this to, say, COPD or congestive heart failure — both chronic, both that likely could benefit from online communities/support, but who generally are older and unused to, or unfamiliar with, the idea of online communities.

At any rate, intriguing. Thank you.

Yes, in 2010 we asked a similar question but didn’t put a time limitation on it. We found that 18% of internet users had gone online to find others who might have health concerns similar to theirs (and it was higher among people living with chronic conditions).

The full report on that topic is on our site: Peer-to-peer Healthcare

http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/P2PHealthcare.aspx

This year, we decided to add “in the past 12 months” to some of our questions in order to bring them into line with other research organizations’ questions. That resulted in some of the trends dropping a bit, but nothing out of the ordinary.

I think this data serves as a reminder to everyone to keep the big picture in mind. Even as there is interest, hope, and excitement about the potential for online health resources making a difference in people’s lives, only a small group of people are tapping into the network in a deep, meaningful way. If you think it should be a broader-based movement, you now know where you stand. If you think more rules or guidance should be in place before people connect with each other online, you also know the state of play.

Ah yes, the big picture … and cognitive biases. “We don’t see things as they are, we see things as we are” (Anais Nin). I suppose it’s no surprise that [some] ePatients by their nature would be surprised that more people aren’t like them, i.e., searching for useful information and supportive community online.

Naomi’s differentiation between chronic conditions such as MS and COPD or congestive heart failure remind me of an earlier thread of an earlier discussion about the role of shame in seeking out information. For example, the information-seeking and/or community-seeking behavior – online vs. offline – may be very different for health challenges for which people are more likely to feel shame (e.g., sexually transmitted diseases or nearly any mental health problem) than those which seem to have broader acceptance in society (such as those mentioned by Naomi).

Susannah: knowing you, I’m sure you’re already planning out the next several health surveys, and have no shortage of possible angles to pursue. However, as you know, I’m not shy about proposing new angles … and I wonder if Brene Brown – in my opinion, the world’s foremost shame (and shame resilience) researcher – might help inform ways of teasing out the interplay between shame and health … and health information.

I’m curious as to why the portion of respondents who consult/contribute to online rankings has basically stayed flat. I suspect part of it is that people don’t see the relationship they have with their health care providers in the same way they see the relationship they have with other service providers, such as plumbers. You have to make an emotional leap of faith when you put yourself or a loved one in someone’s care. You as the object of fixing is emotionally different from your washing machine as the object. Given that premise of faith and trust, I think that makes it hard for people to rate. It’s easy to rate when someone lives up to your expectations or totally blows them. But when it’s a 2-4 out of 5, that’s harder to grade. But I wonder what others think.

Great report! Thank you!

To Paul’s point about health care services and products being viewed as different than other services say your plumber, I would agree. I thought the data that 80% of people saying they had researched a product or service online; but only 20% has consulted online reviews for clinicians or medical services, was very telling.

This speaks perhaps the social contract between medical professionals and the community and underlining cultural assumptions that health care is a different kind of good. Many people trust that health professionals will uphold this social covenant, and do feel the need to read online comments they way they might when looking for a new hairdresser. However, when so much of the pricing for medical services and care is no longer set by medical professionals, it seems health care is increasingly a consumer good, and we should treat it as such in online reviews and searches.

My second comment has to do with the high percentage of online diagnosers (over 1/3) who decided they didn’t need to go to a clinic after an online search. Is there a way to translate this into $/time saved in the health care system by providing people with online information and perhaps consultations? Can it translate into a e/mHealth triage system prior to making appointments?

Paul (& Susannah),

I have a long time theory about your question. When people look for plumbers they try to either look for a good plumber or avoid a bad one. When looking for doctors the expectations are different.

We have all been raised with the idea that it is difficult to be a doctor and that the strong filtering is done early on, to train only people who will be good doctors. This, and the licensing process, makes us assume, even unconsciously that our visits to a doctor’s office are inherently safe because we are facing a professional who knows what she is doing.

So what happens when people are asked about their doctors? In our online communities the phenomenon is pretty clear. If you’re diagnosed with cancer, your view of what’s important changes dramatically. Why spend any time rating down a doc when it’s so much easier to just switch? Spend the time instead explaining who the great doctors are, which, in the end, is the only important fact.

You just want your fellow travelers to get great care. You only mention the good doctors. Let 500 people do that and now you can compile the list of true experts who are the only one able to provide you with optimal care. Of course, this model doesn’t apply to all of medicine because the stakes are different if you deal with a cold or kidney cancer. But for complex conditions, the reputation system based exclusively on rating up works wonders.

Another cutting edge report from Pew! Cool Stuff! One of the most fascinating findings to me: “Fully 83% of those who hit a pay wall say they tried to find the same information somewhere else. Thirteen percent of those who hit a pay wall say they just gave up.” With this search pattern, I am interested in thoughts of how to get credible and reliable health info to consumers! Also what are the implications for business models if consumers avoid and bounce off of pay walls?

As always great report, what caught my attention is the fact that Eight in 10 online health inquiries start at a search engine, it appears that after all the years and investments in health portals patients has not picked a clear winner in the health vertical, http://www.tripadvisor.com won the travel, http://www.yelp.com won the local related searches, and the number one spot in the Healthcare domain is vacant, I can think of many reasons for the vacant spot, it is costly to generate new health info, the long tail nature of health, regulation, and at the same time I assume that this will change in the next 2-4 years.

Gideon, I just wanted to let you know that I cited your comment in 2 press interviews yesterday and linked here in follow-up emails. Thanks so much for adding that insight!

Sure.

Saw that you have a paper on caregivers coming out in Feb, we have great content on it (we have a customer that asked us to review caregivers and MS medications) would love showing it to you.

Gideon

I’d like to know more about the pay-wall. Is this the information in medical journals? While serious researchers understand the value in original source material, the major news outlets do a good job of reporting on the important findings. A greater concern for me is the use of a basic search engines to look for health information. The good sources are being underutilized.

Hi Mark,

Unfortunately we don’t know the details about which sites people were visiting that asked them to pay. Definitely something we’d like to follow up on (and maybe a different kind of research would answer better — how about traffic logs from major journals? How many people hit the pay wall and bail out?)

Sure! As you found, many patients and caregivers give up when they run into that paywall. They may not realize that they may very well already have free access to that article available to them through their public library — or they may be able to get free access to it by contacting a medical library or other academic library in their area. Here’s what they can do:

1. Copy down the citation information for the item, or simply print out the paywall page (which usually contains the citation information).

2. Call, email, or visit their local public library to ask for help getting the article. In many cases, public libraries subscribe to health information databases that may include the full text of the desired article — and often, all you need is a valid library card to access them from your own home computer. If your public library doesn’t have the article you need,

3. Look for a medical library or other college/university library in the area, call them and ask if the public can come and use their facilities (and computers). College and university libraries usually subscribe to much more scientific literature than the typical public library, and although access “off campus” will be limited to students, faculty or staff, access to all of those e-journals is generally available to anyone *on campus*. At our public university medical school library, we’re happy to help members of the public access the online content we subscribe to. Patients and caregivers can come and use a computer in our library, and while they’re here, they have access to everything our own doctors and students do (including help from friendly librarians). Finally,

4. if you’re not able to go to a college or university library, ask your local public library if they can get the article for you through a service called “interlibrary loan”. Most libraries offer this service, which means if they don’t own the material you need locally, they will request it on your behalf from other libraries across the nation. It may take a few days for them to get you an article through interlibrary loan, but in most cases, it’s a free service for library members.

In short, your public library card — and your friendly local librarian — hold the keys to unlocking secret doors in the paywall. How can we help more patients and caregivers learn about these options?

Agree that libraries are WONDERFUL resources to gain access to medical and health journals/information. I’m a card-carrying research geek and I access PubMed often. But, in this age of getting everything on-demand (tv, movies, music, news, etc.), for many consumers, having to wait a couple of days (or even a couple of minutes!) may be viewed as a barrier. And they look for information elsewhere or just quit. I believe that is the point of the Pew finding. If there were ways for libraries to make it easier for their members to access information (on-demand, or just-in-time), that would be really cool!

The distinction between research journals and other online searches is fascinating. Credible research journals are peer-reviewed and managed by editorial staff. Information has been reviewed and vetted. But, I agree with Mark Harmel that of more concern is the use of basic search engines to seek health information. Since most consumers start with basic search engines when seeking health information (as noted by the Pew study), it would be interesting to know how consumers gauge the credibility and value of paid vs. free health websites. Do consumers believe that there is valuable and credible information behind the paywall but are not willing to pay for it? Do consumers believe that they should not have to pay for credible health information and that sites that charge money to gain access are untrustworthy? What is the price point consumers would be willing to pay for information they believed was credible? For free websites where consumers migrate, how do consumers determine credibility and trustworthiness? Is there an easy way for consumers to determine information credibility?

So, the Pew study, for me, opens up a whole new series of questions. Excellent fodder for future survey and experimental research! :)

great discussion about the resources for the public to obtain “closed-access” medical info. I am surprised as much as 2% of them pay for the info upfront…

I would have thought so too … but according to a 2010 Pew Internet study, Paying for Content, found that “65% of internet users have paid to access or download some kind of digital content”, and while music and software are the most popular content for which people are paying for (33% each), “18% have paid for digital newspaper, magazine, or journal articles or reports”.

Holy cow, it’s a red-letter day when someone beats me at citing Pew Internet’s data – thanks, Joe!

I’d love to dig deeper into this – what do people expect to get for free? What are they willing to pay for? Why? If anyone knows of related research, in any sector, please post it.

Dave was so nice to write a “Heads up” post on Monday – he inspired me to write up an overview of the NEXT three health reports we’ve got cooking at Pew Internet.

From my personal blog: 2 down, 3 to go

Essentially:

1) Mobile (done)

2) Health Online – general population (done)

3) Health data tracking (end of Jan)

4) Caregivers (Feb)

5) People living with chronic conditions (March)

Let me know if you have a special interest in any of these and I’ll add you to the preview copy list (provided you double-pinkie swear not to share the results before we publish them). Just email me: sfox at pewinternet.org

Great stuff as always and prompts as many questions as it answers, which is also excellent. Some of the most notable findings to me included: 1) the documented lack of a difference for online diagnosers despite insurance status, 2) the high correlation for ‘clinically confirmed’ diagnosis, and 3) the non-Pew-novel, but underappreciated high percentage of searches conducted for someone else.

It was also encouraging to see that interviews were conducted in English and Spanish – it may prove useful to see results by those characteristics as well. Similarly, it would be interesting to see more about the nature of the inquiries for mobile vs desktop searches and for self vs others.

Coming back to several of the comments on search engines, I continue to hold out hope that a dot health (.health) top-level-domain can become an effective reality.

Thanks, Kevin! There is SO MUCH DATA to analyze, the head spins. That’s why I am proud to say that Pew Internet has been open access all along. As soon as we publish the final report based on a survey, we post the data online:

http://www.pewinternet.org/Data-Tools/Download-Data.aspx

Note to everyone: Kevin had trouble posting a comment yesterday and luckily had my email address so he could let me know. If you ever need help with this site, don’t see one of your comments pop up, etc. please feel free to ping me: sfox at pewinternet.org

Great report as always Susannah!

One of the things I was pondering was this apparent decline in people using reviews of drugs or other medical treatments from 24% in 2010 to 18% in 2012. One possibility might be that by-and-large, what is known about drugs, their side effects, and their efficacy, doesn’t change that dynamically. As the question timeframe looks like it was “in the last 12 months”, maybe this reflects that most information about treatments is static (e.g. Wikipedia) and that once you’ve already read it once, you don’t gain much more by going back to it.

Also if you’ve started taking the treatment, you probably know more about it than is available from those sources pretty quickly! Contrast that with other common review sites; a restaurant could change chef, a bar could change managers, an airline could be taken over. But drug X is still drug X and most of the information still comes from the trial that got it approved in the first place – we don’t yet have a dynamic learning system that gains from the experience of every patient using a treatment. Yet.

Cheers

Paul

Thanks for making the jump from Twitter to posting here, Paul — always good to stretch one’s legs in a bigger text box, right?

We added “in the past 12 months” to many questions in this survey, but not this series.

Here’s the question wording:

ASK ALL INTERNET USERS:

Q20 Thinking again about health-related activities you may or may not do online, have you… [INSERT ITEM; RANDOMIZE]? (Next,) have you…[INSERT ITEM]?

a. Consulted online rankings or reviews of doctors or other providers

b. Consulted online rankings or reviews of hospitals or other medical facilities

c. Consulted online reviews of particular drugs or medical treatments

d. Posted a review online of a doctor

e. Posted a review online of a hospital

f. Posted your experiences with a particular drug or medical treatment online

CATEGORIES

1 Yes

2 No

8 (DO NOT READ) Don’t know

9 (DO NOT READ) Refused

But you’re on to something. There is a fundamental difference between drug reviews and nearly any other product or service. The users (and/or caregivers) are truly the experts, the directors of their own N=1 trials.

Great report. Thanks so much for your work. Wonderful detail about who is using online resources, and how they are using them.

We have found similar rates of online use in our consumer survey, yet online sources still lag far behind friends and family as the most frequently used information for finding a provider.

Still a very interesting stage of evolution!

If anyone is interested in our survey, it’s here:

Altarum Institute Survey of Consumer Health Care Opinions (PDF)

Again thanks.

Wendy