At 9am on Sunday, Sept. 7, 2014, Stanford Medicine X will host a discussion led by Pamela Ressler, Colleen Young, Meredith Gould and me about the power and pitfalls of people sharing their health experiences online.

We are “flipping” the panel by sharing resources and participating in online discussions throughout the summer, hoping to include as many people as possible in the process. You can check out our Storify, which lists our ongoing series of blog posts (this one is the second — Pam kicked it off on her blog last week.)

I thought I’d share some historical context. Because really, none of what we plan to discuss is new. It’s ancient. People have always gathered together to share what they know about health and illness, hoping to help and learn from others. What’s new is that we have the ability to expand our networks, inject more data and background resources into the conversation, and then archive them for later searching or other use.

For example, in 1999, Tom Ferguson, MD, fielded a small-sample survey of people who were using online health discussion forums, asking them to rate the resources available to them for 12 dimensions of medical care. His findings were as follows:

- Most Cost Effective

Online Groups–82.68 percent

Specialist MD–8.38

Primary Care MD–8.94 - Best In-depth Information on My Condition

Online Groups–76.92

Specialist MD–20.88

Primary Care MD–2.20 - Best Help with Emotional Issues

Online Groups–74.73

Specialist MD–9.89

Primary Care MD–15.38 - Most Convenient

Online Groups–72.68

Specialist MD–14.21

Primary Care MD–13.11 - Best for Helping Me Find Other Medical Resources

Online Groups–68.68

Specialist MD–14.29

Primary Care MD–17.03 - Best Practical Knowledge of My Condition

Online Groups–68.48

Specialist MD–23.37

Primary Care MD–8.15 - Best Help with Issues of Death and Dying

Online Groups–57.50

Specialist MD–15.00

Primary Care MD–27.50 - Most Compassion and Empathy

Online Groups–52.46

Specialist MD–17.49

Primary Care MD–30.05 - Most Likely to be There for Me in the Long Run

Online Groups–49.43

Specialist MD–21.02

Primary Care MD–29.55 - Best Technical Knowledge of My Condition

Online Groups–47.54

Specialist MD–44.81

Primary Care MD–7.65 - Best Help and Advice on Management After Diagnosis

Online Groups–34.59

Specialist MD–42.70

Primary Care MD–22.70 - Best Help to Diagnose My Problem Correctly

Online Groups–11.35

Specialist MD–73.51

Primary Care MD–15.14

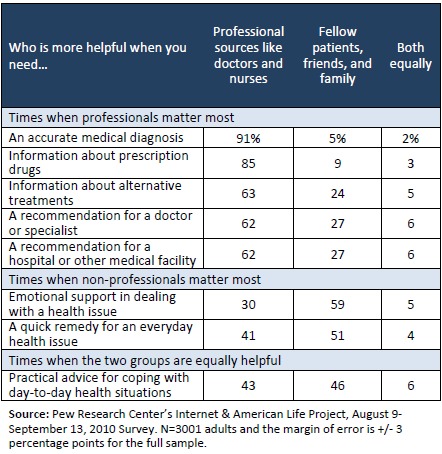

The Pew Research Center fielded similar questions in a national telephone survey in 2010 and guess what? We found essentially the same thing, a decade later:

To bring it up to the present day, Matt Wilsey and Matthew Might recently co-authored a commentary in the journal of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics: “The shifting model in clinical diagnostics: how next-generation sequencing and families are altering the way rare diseases are discovered, studied, and treated.”

Here’s an excerpt:

Until very recently, the fragmented distribution of patients across institutions hindered the discovery of new rare diseases. Clinicians working with a single, isolated patient could steadily eliminate known disorders but do little more. Families would seek clinicians with the longest history and largest clinic volume to increase their chances of finding a second case, but what does a physician do when N = 1 or if the phenotype is inconsistent across patients?

Answer: They search online. They find a blog post. They find each other.

People who were isolated, who probably would never have found the answers to their questions, are able to connect thanks to the confluence of new genetic testing, easy access to publishing platforms, and ever-improving search algorithms. It seems like magic, especially if you’re new to peer-to-peer health care.

It is cases like this one which inspired me, in 2011, to write, “The internet gives patients and caregivers access not only to information, but also to each other.” It is also why I tell people, “the most exciting innovation of the connected health era is people talking with each other.”

There is no such thing as over-sharing when you are pursuing hope “like it’s an outlaw” (to quote Afternoon Napper). To say otherwise is to deny people the chance to change the way we practice medicine, for the better.

Now: what do you think? What historical examples of patient networking do you know about — offline or online? Has the internet changed things — for the better or for the worse? I’d love to hear what you think — join the discussion in the comments or on Twitter using the hashtag #medx. The conversation is never over!

We are sharing stories on the air at Stories With A Purpose on ITunes.

I have always felt that our experience as patients is way harder than it needs to be. Why is it that every patient has to begin a learning process from scratch without the benefit of the experience of others? Is it really necessary to reinvent the wheel at each diagnosis? When you think about it, we are all standing on the shoulders of thousands of patients who have been through our situation and probably much worse. The problem is the patient never gets any benefit of the experience of others while the doctors do. We patients tend to be isolated in the flow of information, experience of others and we emotionally cut off by a medical system whose focus is strictly clinical.

In telling my own story I realized how valuable my experience has been for others who continue to struggle or are helping someone navigate through the healthcare system. People learn best from others like them. And that is why my company Smart Patient Academy created the Stories With A Purpose (SWAP) platform. The goal of the program is to break down the silos of valuable wisdom, insight and experience that stay bottled up in our own memories, infrequently shared with those who could truly benefit. The healthcare delivery system needs to change. You and I as patients can make this happen.

As people tell their stories we have found that there is almost always one dominant character trait or attribute that enables each of us to navigate through the emotional battlefront that nobody every talks about. So we have organized our podcasts both by medical condition as well as by human virtue. For example, I personally used “Humor” to joke my way through the process. It is just my way of coping and working the system. (Listen to some of the Vignettes we have posted and see if you agree.) Or get a taste of “Persistence”, “Courage”, or “Resourcefulness” – all characters that have used their God-given virtues to improve their own outcomes dramatically.

Thanks, Jim – looks like an interesting resources!

I love this! Thanks so much for sharing it. Have you seen patterns in either the number of people who share a certain trait OR the popularity of certain podcasts?

Good question. We did not anticipate the personality virtues being part of the success of each patient so we are still in the process of identifying patterns. So far we have seen a wide spectrum of virtues that appear to be innate tendencies of each. The crisis causes patients to dig deep into their bank of resources and Viola!, out comes the virtue as a tool. Virtually all of them are surprised and only modestly accept a survival mechanism as a character virtue.

I realized that “flipping” might be an unfamiliar concept to some people, so I’ll add a few background documents:

Here is a Wikipedia article on Flip teaching. The Khan Academy is a famous example.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Flip the Clinic initiative takes the concept a step further toward health care.

I flipped my own presentation last January, asking my community to help me and starting the conversation online.

First /impressions/ideas: Great concept but hard to implement scale up for all but the most Expert Patients. I am extatic to see providers with this perspective so congrats. Here are some of the assumptions that can become big hurdles to the success of Flipping the Clinic

a) active/engaged patient – might not be

b) receptive not hostile MD – frequently not

c) tech savey patient – young yes/not older

d) analytical patient not intimidated by fear and emotion which happens about only 15% of the time.

e) understands financial impact of the flip the clinic interaction with provider and insurance.

Yes, and thank you, Jim, for another great comment (in case you haven’t clicked through to the Storify, I updated it with an excerpt from your first comment).

I think Flip the Clinic is meant to be a Dream Big exercise, stretching people who are ready to be stretched. Similarly, this idea of flipping the panel is another exercise meant for people who are already pretty engaged in the topic, who may or may not be able to attend or watch the livestream of the event in September but who want to contribute. This admittedly describes a small group of people.

In fact, when I was telling a friend of mine about Stanford Medicine X and this panel, she gently pointed out that I was preaching to the choir. Why go, she asked, when you already know that most of the people there will agree with you that people should be able and even be encouraged to chronicle their own health & illness however they please?

I thought about it and replied that Medicine X (and other, similar events) are like a hive we return to once a year, to renew ourselves. Outside the hive we are so often the weird ones, the wild ones, the seers and the gypsies of health care. Together, once a year, we are a tribe.

To keep myself grounded, I also try to attend events with “regular” people — those not yet on the Twitter or blog bandwagon, for example. And it is clear that you keep yourself connected to reality by continuing to canvas for and collect new stories.

To your points, I would say yes, you’re right. Those are the roadblocks. Can we measure them? Can we track them, so that if they rise or fall we will know? Can we find shortcuts around them and somehow publicize those tricks and tips?

Thanks Susannah for the redirect to Storify.

Am really glad you created an annual break for the thought leader tribe. Really necessary.

We are definitely on the same page. Our efforts include: recording and publicizing the patient navigation strategies via Smart Patient Academy. Book on Amazon: Smart Patient Smart Money – The Essential Playbook for the New Healthcare Consumer.

Our show on ITunes : Stories With A Purpose allows patients to stand on the shoulders of other patients and learn how to navigate the system, clinically, emotionally and financially.

Thank you, Jim for joining the discussion we will be having at MedX. I look forward to learning more about Stories with a Purpose on ITunes.

Susannah,

I’ve had a recent experience connecting with others as an e-patient that totally blew my mind. This absolutely could not have happened without looking for, participating in and learning from an online patient community.

Let me work backward. I have metastatic lobular breast cancer, a type of cancer that has a tendency to spread into the gastrointestinal tract (among the usual places of lung, liver, bone and brain). It is also a type of cancer that does not image well at all, consequently most women tend to be diagnosed at a later stage. The cells often spread in a single file as opposed to clustering and forming a tumor. Lobular breast cancer, in and of itself, only comprises about 10 – 15 percent of all breast cancer cases. And of those, not even five percent metastasize to the stomach. I discovered last October that my cancer had spread into my stomach.

Through the quirk of connectedness in an online patient community, I not only met another woman who has stomach mets but she went on to form a private group. In less than a week there are twelve of us with a rare manifestation of an already unusual cancer. I can’t see how this would have happened otherwise. We can now enjoy all the advantages fellow travelers share with each other — the ups, downs, the research, the side effects, the solutions.

You know, I never thought I’d be in this situation but I’m so grateful to have discovered these other women. As you said, none of this — the need to share, affirm, and exchange — is new. But it is new to me and to have company through this unusual detour is priceless.

Thanks for all you do.

That is great to hear Jody. It would be great to learn more about how the group got formed and how you found out about it. This should not be a situation of good luck but rather a process that needs to be made widely available. Can you share more?

Thanks

PS. You sound really strong!