Next in our #DocTom10 series, which started here. Today we resume our review of the chapters of Tom’s White Paper.

Next in our #DocTom10 series, which started here. Today we resume our review of the chapters of Tom’s White Paper.

This Foreword stands on its own, with no comment needed, so we’ll just paste it in verbatim.

Note: these numbers are from 2000, when the Web was just six years old! E-patients have been e–patients a lot longer than skeptics believe.

Foreword

By Lee Rainie and Susannah Fox

The Pew Internet & American Life Project

It gives us great pleasure to recommend this white paper—and its author—to everyone interested in understanding how our first generation of e-patients is slowly but surely transforming our healthcare system. For we have learned a great deal about the emerging e-patient revolution from its author, Tom Ferguson, and from his team of expert advisors and reviewers.

We first met Tom in November 2000, shortly after the release of the Pew Internet & American Life Project’s first e-patient survey, The Online Health Care Revolution: How the Web Helps Americans Take Better Care of Themselves.[i] Tom had addressed many of the same topics in his book, Health Online: How to Find Health Information, Support Groups, and Self-Help Communities in Cyberspace,[ii] so he was asked to critique our report—while Lee was invited to defend it—on a live National Public Radio call-in talk show.

But if the producers had expected to trigger a battle between competing author-researchers they were badly disappointed, for Tom was generous and enthusiastic in his praise, calling our report “the most important study of e-patients ever conducted,” and insisting that our conclusions were exactly in line with his own observations:

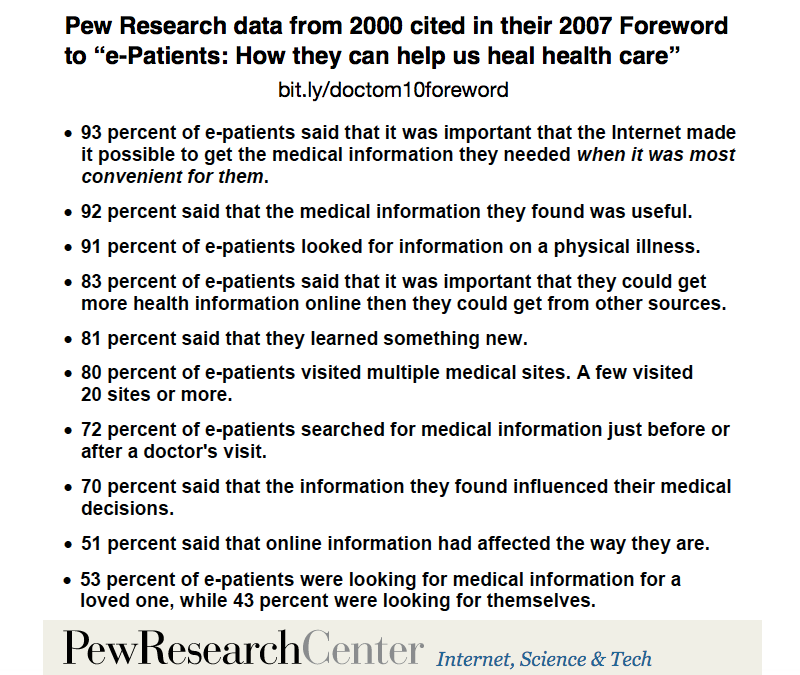

- 93 percent of e-patients said that it was important that the Internet made it possible to get the medical information they needed when it was most convenient for them.

- 92 percent said that the medical information they found was useful.

- 91 percent of e-patients looked for information on a physical illness.

- 83 percent of e-patients said that it was important that they could get more health information online then they could get from other sources.

- 81 percent said that they learned something new.

- 80 percent of e-patients visited multiple medical sites. A few visited 20 sites or more.

- 72 percent of e-patients searched for medical information just before or after a doctor’s visit.

- 70 percent said that the information they found influenced their medical decisions.

- 51 percent said that online information had affected the way they are.

- 53 percent of e-patients were looking for medical information for a loved one, while 43 percent were looking for themselves.

When the program ended, they continued their conversation by phone. Tom came to our offices in Washington DC a few days later, and the three of us talked intently for several hours. Before he left, we invited him to join our Pew Internet health research team. So we were not surprised to hear that when the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation decided to explore the experiences of our first generation of e-patients, they turned to Tom for help.

The project design they came up with was most ingenious: Tom wanted to assemble a team of leading researchers, developers, and visionaries in the emerging field of e-patient studies. These advisors would help him frame the questions to be explored. The advisors—and an even larger group of expert reviewers—would then review and critique successive drafts of each chapter. This document thus reflects the perspectives of the many diverse collaborators Tom has brought together, sometimes virtually and sometimes physically, to consider these vital topics.

We have been honored to play some modest part in this process, serving as editors and co-authors of Chapter One, which reviews the results of our first five years of e-patient surveys, and reviewing and commenting on many of the other chapters. And we have been lucky enough to get the chance to meet and work with many of Tom’s other collaborators.

In the pages that follow, you will find a uniquely helpful overview of the contemporary e-patient revolution. Tom and his colleagues suggest that this massive, complex, unplanned, unprecedented, and spontaneous medical empowerment of our lay citizens may turn out to be the most important medical transformation of our lifetimes. The world of the e-patient as they portray it is not a dry, impersonal realm of facts and data, but a living, breathing interactive world in which growing numbers of our fellow-citizens—both patients and professionals—interact in highly personal and fully human ways.

Tom and his colleagues have done us all a further service by combining their detailed and compelling portrait of the emerging e-patient phenomenon with an unusually original and creative set of tentative suggestions for leveraging the most promising developments from the e-patient experience in the most suitable, sustainable, and productive ways.

This white paper offers a variety of helpful perspectives on the e-patient experience. There is something for everyone:

Clinicians will be reassured to find that many of our early fears about the potential dangers of patients using the Internet have been proven largely groundless. They will learn a great deal about collaborating with their own e-patients. And those who have [iii]resisted or discouraged their patients’ use of the Internet will find a compelling explanation of the benefits of becoming more “Net-friendly.”

Medical executives, policymakers, employers, insurance executives, government officials, and others seeking solutions to our most troublesome and intractable healthcare problems will find an unprecedented array of powerful and promising solutions for sustainable healthcare improvement and reform.

e-Patients and potential e-patients—and this means all of us—will find confirmation of our online experiences, inspiring stories of what other e-patients have accomplished, and suggestions of even more sophisticated ways we might use the Internet to obtain the best possible medical care for ourselves and our loved ones.

Researchers like ourselves will find many fascinating new hypotheses and questions to consider: How is it that the groups of expert amateurs Tom and friends describe are able to provide their members with such valuable medical help? To what extent can shared experiences and advice from patient-peers supplement or replace the need for professional advice and care? Now that anyone with a modem can publish information, what new quality practices and resources do e-patients use to avoid problems and stay out of trouble? What will be the consequences of turning the previous century’s old doctor knows best model of medical information flow upside down? How often and in what cases do patients actually know best? Might it eventually be those wise clinicians and patients who collaborate via the new models presented here who know the most of all? And at the pinnacle of this research mountain sits an even more profound question: Are these technologies changing our traditional patterns of social connection so radically that we may need to begin thinking about our first generations of online humans as homo connectus?

Tom and his colleagues understand that the conclusions they offer here are not the final word on these topics. As they repeatedly suggest, additional perspectives, more innovative research, and further demonstration projects are badly needed. And they intend to make this a living document, inviting readers with ideas, comments, or additional research agendas to join with the current collaborators in imagining, and in continually updating, a vision of our common healthcare future.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation staffers who invited Tom and his team to prepare this document should be proud to have helped create such a valuable resource and roadmap. May the chapters that follow prove as useful to you as they have already been for us. We hope you will review its conclusions, consider its recommendations, and then join us via the projects’ new weblog, www.e-patients.net.

[i] Susannah Fox and Lee Rainie, The Online Health Care Revolution: How the Web helps Americans take better care of themselves, Pew Internet & American Life Project, Washington DC, Nov. 26, 2000. (Original URL: http://www.pewinternet.org/PPF/r/26/report_display.asp (Accessed Aug. 6, 2004). )

[ii] Tom Ferguson, Health Online: How to Find Health Information, Support Groups, and Self-Help Communities in Cyberspace, (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley/Perseus Books, 1995).

Recent Comments