Next in our #DocTom10 series, which started here.

Next in our #DocTom10 series, which started here.

I first met Tom Ferguson in 1994 online (where else?) when he reached out via email to chat about online support groups. I was still in graduate school at the time, and he had come across my indexes of Internet support groups for health and mental health concerns. He was writing a book (“Health Online”) and wanted to better understand these kinds of self-help groups.

Tom Ferguson was a voracious inquirer and accumulator of knowledge, with a wonderful sense of humor. His brain seemed like it was full of millions of facts and ideas that he was always excited to share with you.

Tom was also a great disruptor of the status-quo. He understood that could best be done by bringing like-minded people together from different fields and perspectives to help change healthcare.

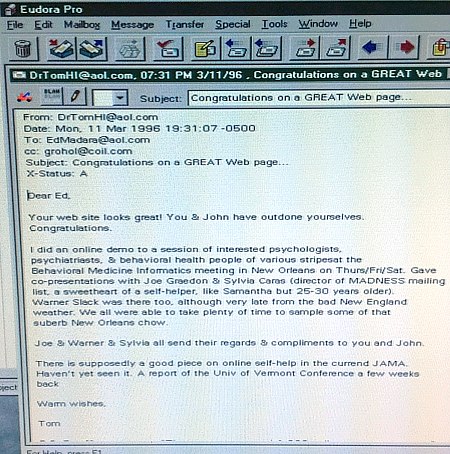

Tom’s rare quality — of being at the center of a network allowing people from diverse backgrounds get to know and network with one another — was particularly valuable pre-web. He immediately put me in touch with Ed Madara, a community leader at CompuServe and the director of the now-defunct American Self-Help Clearinghouse (a resource of information about every self-help group in the U.S.). Ed and I did a lot of good work together in the late 1990s — something that would’ve never have happened without Tom’s introduction.

I didn’t know much about Tom before we started exchanging emails on a regular basis (and Internet searching isn’t at all what it is today, so there was no quick Googling of his background). So when I first started emailing him, I didn’t know he had started his own magazine (Medical Self-Care) or was the medical editor of The Whole Earth Catalog. I just knew he was an author of a few books and had a warm demeanor (that came through even via email).

You always came away from a meeting or conversation with Tom feeling like a better person. He renewed my hope every time I spoke to him. He seemed like an eternal optimist in his demeanor, but also had an acute mind that realized the complexities of the systems he battled. He didn’t just “think outside the box,” he thought outside of the whole system. He imagined a world without boxes but that instead was composed of interconnected circles of mutual respect, trust, and exchange. In short, he wrote his own rules and followed his own drummer. He was a visionary far before his time.

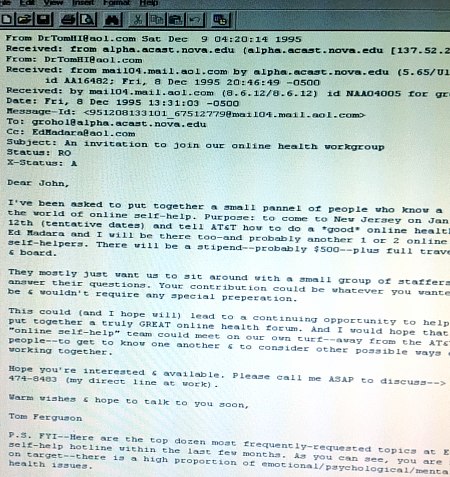

Tom’s fascination, curiosity, and promotion of online self-help was seemingly limitless. I first met Tom face-to-face when he put together a small group to help consult with AT&T in early 1996. AT&T was trying to develop their own online commercial service and wanted to better understand self-help groups and online community.

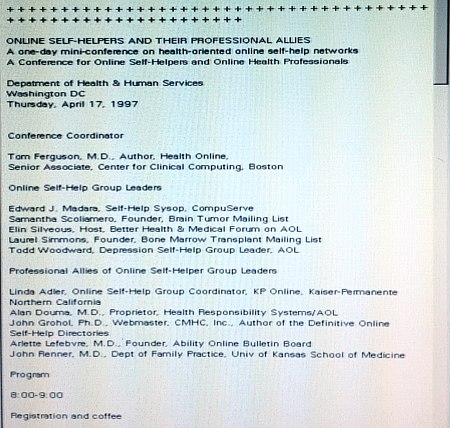

He also organized a national conference for the Department of Health and Human Services on April 17, 1997 in Washington, DC entitled, Online Self-Helps and Their Professional Allies: A one-day mini-conference on health-oriented online self-help networks. This conference brought into the national spotlight the value of online self-help, with a diverse group of consumer leaders and professionals (including myself). Samantha Scoliamero, founder of the Brain Tumor (BRAINTMR) Mailing List, was one of the attendees and easily one of the first e-patients, long before the term was ever coined.

Tom was one of the first people to realize and understand the importance of self-care — that most health care is actually done long before a person ever reaches out to talk to a professional or physician. So in 1997, Tom organized and hosted the first Cook’s Branch retreat at his wife’s family ranch and conservatory north of Houston, Texas. The Cook’s Branch retreats turned into a series of “meeting of the minds” in thinking up ways to disrupt the current U.S. healthcare system and get more people to realize that most health care actually occurs outside of a hospital or doctor’s office.

At the Cook’s Branch retreats, I ended up meeting many lifelong friends and colleagues. These include some of the pioneering online community leaders, such as the pragmatic visionary Gilles Frydman (ACOR, and now the innovative Smart Patients), the curious and creative John Lester (now at OpenText) & Dan Hoch (neurologist) of Brain Talk, the engaging intellectual Danny Sands (doctor, longtime director at Cisco, now consultant), the couple behind the amazing People’s Pharmacy, Joe & Terry Graedon, Charles Smith (ahead-of-the-curve doctor who founded eDocAmerica), and the couple behind the premier online pediatric resource, DrGreene.com, Alan & Cheryl Greene. Later on I would meet other extraordinary people: innovator Sarah Greene, early Internet pioneer Jon Lebkowsky, the energetic, focused Internet geologist Susannah Fox, and of course, the indubitable, unflagging e-Patient Dave. I also got to know the two biggest supporter’s of Tom’s work: his wife, Meredith Dreiss, as well as his long-time assistant and right-hand woman, Anna Bryan.

Tom brought together a diverse group of patients, professionals and others both inside and outside of the health care system to brainstorm and imagine a different world, where everyone was in charge of their own healthcare… Where people, if they wanted, could become equal partners and the drivers of their own care and treatment.

The Society for Participatory Medicine was born from such meetings. When Tom passed ten years ago, the group met for what might have been one last time at Cook’s Branch to honor Tom’s memory and decide what to do next. “What to do next” turned out to be that we should try and carry on Tom’s legacy — through the work of the Journal of Participatory Medicine and the Society for Participatory Medicine.

When I moved to Tom’s hometown of Austin, Texas in 1999, he welcomed me warmly like a family member. We spent some good times together that year, and he helped me through a pretty tough time in my personal and professional life. He was always there for me, always willing to lend an empathetic ear, always coming up with some new ideas to explore.

Tom kept my hope alive when I was in a place in my life where I had lost a lot of it.

So in memory of Tom, I raise my glass to you — may the world never forget what you did, the ideas you sparked, and the bonds you helped forge that remain strong to this day. Your legacy lives on.

Yes, I’m a digital packrat, and have most emails archived that I’ve ever sent or received!

Yes, I’m a digital packrat, and have most emails archived that I’ve ever sent or received!

Thank you, John, for sharing those memories of Tom. I am envious of your email hoard! I wish I had access to my correspondence with Tom.

I’d like to share my personal reflection of Tom’s legacy and what we can learn from him, still. This was a comment I wrote on my personal blog, in response to someone who asked, with understandable frustration, why Tom’s ideas from the 1970s, 80s, and 90s are still not mainstream:

Tom’s vision has not yet been fully realized. But it does continue to emerge.

You can catch glimpses of it, in pockets of the country, such as when Open Notes was rolled out and, “after 12 months, 99% of patients wanted to continue to have access to their notes online and none of the doctors decided to stop the practice.” (BMJ, 2015)

If I had time, I would write another post like, “Peer-to-peer Healthcare: Crazy. Crazy. Crazy. Obvious.”

Or I’d evaluate how many of Tom’s predictions had come true.

But I’ll share some advice I recently received. Someone said to me: Your career has been a mix of analyzing things and building things. Resist analyzing. Build.

I’ll also share this memory of Tom. When he was quite ill — “bald as a cue ball” from chemo, as he put it — he came to DC for a visit. I don’t remember the details, but there had been some setback in the e-patient movement, some cutting remark by a prominent doubter, some news article that had got it all wrong.

I asked him how he was able to maintain his sunny optimism. He was smiling, even as he was a decade into cancer treatment and four decades into the fight for patient empowerment. I believe that some of his optimism might be genetic — a pioneer, entrepreneurial spirit — but his answer took no personal credit. He talked about his Zen practice, his focus on gratitude and to “be here now.” To be in the moment, at all times, is to exist in possibility.

My interpretation is that “be here now” contains the possibility that your reality — of finding a hospital that welcomes empowered patients, for example, as Tom did — is one that can animate the world.

Around the same time, I had lunch with Jim Clay, the director of the preschool my children attended, School for Friends. It is a school that not only embraces diversity, but welcomes every aspect of a new family or challenging situation as an opportunity for everyone to learn, to deepen their understanding of their role in the community.

In my food-allergy (FA) support group, I’ve read many stories of schools which exclude FA kids — either by not admitting them, by outright telling parents that they cannot guarantee an FA child’s safety, or by refusing to accommodate a family’s requests for safety measures. Jim took the opposite tack. As soon as he found out that my son had FA, he called a meeting of all the teachers and we conducted in-depth training on not only the safety issues, but the social issues of FA. He then publicized the new policies to all parents, letting it be known that FA was something we as a school community would embrace.

Most parents followed the new rules without complaint. A handful did not. They complained. They asked why they couldn’t bring XYZ food. Jim was unswerving, as were the teachers. And I felt their embrace. I tasted what it would be like to live in a world where differences were celebrated. I now had a mental model for a school environment that was truly safe, that truly had my child’s — every child’s — best interests at heart. It strengthened my resolve when I later encountered school administrators and teachers who did not know how to create such an environment. I could tell them what it looked like, how we could achieve it, because I had seen it, not just in my minds-eye, but in practice, under Jim’s leadership.

Over lunch that long-ago day, I asked Jim how he maintained his optimism, his resolve to create a school environment that was a reflection of his vision for a better world. We had been talking about parents who were resisting the FA policies, but they were just that week’s examples of people who railed against some policy or change. After 20 years, Jim had seen it all, or so it seemed to me. His answer sticks with me to this day: You just have to keep shining a light on the path. Everyone comes to it eventually.

That, to me, is at the heart of what we’re talking about when we talk about the possible future of health and health care. Tom was shining a light on the path. He was living his vision for what we now are calling patient-centered care. He was unswerving in his demand for it — he had the mental model and would not put up with anything less, but gently, with a smile.

There’s a leap of faith in all of this, I think. Both Tom and Jim set their eyes on a point on the horizon and steer toward it, like it’s the only way to go. Because to them, it is the only way. And that’s what I carry with me — that assurance, that mental model of what could be, that confidence that everyone will come to the path. Eventually.

-end-

May it be so. And may Tom’s memory be a blessing to us all.

I am a professor in the information school at UW-Madison and a doctoral graduate of the NLM Medical Informatics Training Program at Pitt. In 2001 when I was an advanced doc student I met Dr Ferguson at the AMIA Consumer Health postconference, which was attended by a number of patient advocate types–the mix of different communities at this meeting was incredible. I believe he and Susannah Fox spoke together on a panel. 2 years ago while putting together a chapter on the history of health information provision to the public, I discovered just how LONG he had been doing this kind of work. It’s very clear that Dr Ferguson had great impact on the thinking of many, many people over the years.

Hi Catherine,

Good memory! Tom, Lee Rainie and I delivered a joint keynote at AMIA in 2001 and then attended the post-conference.

Through the magic of Google (and good online archives) I found this write-up:

2001 AMIA Symposium — A Medical Odyssey: Visions of the Future and Lessons from the Past

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/430264_3

A beautiful overview of how he touched so many lives. Thanks for writing this, John.

These reminiscences explain so much me about the founders of my movement. I am impressed, humbled, and re-invigorated.