A truly significant moment in the history of medicine happened last Wednesday. I say that after attending almost 500 conferences and policy meetings in the past seven years, and I don’t say it lightly. Something many people think is impossible was presented live on stage: patients, informed and empowered by access to their data and access to tools, are successfully managing a complex and dangerous condition – Type 1 diabetes – on their own.

A truly significant moment in the history of medicine happened last Wednesday. I say that after attending almost 500 conferences and policy meetings in the past seven years, and I don’t say it lightly. Something many people think is impossible was presented live on stage: patients, informed and empowered by access to their data and access to tools, are successfully managing a complex and dangerous condition – Type 1 diabetes – on their own.

Most of them will someday welcome the participation of clinicians, researchers, and industry, but their hashtag is: #WeAreNotWaiting.

Video of the session

Here’s video of the session, from the YouTube livestream archive. (If you don’t yet know about #OpenAPS, background information is below.)

- The presentation, introduced by Gary Wolf (@Agaricus), the head of the Quantified Self movement (47 minutes long)

-

Gary’s wrap-up, introducing co-host Dr. Larry Smarr.

- Larry’s remarks. This venerable scientist (Google search), TEDMED speaker and subject of The Atlantic’s article The Measured Man, is seeing his vision materialize: here he said, “That was one of the most moving and important events on this stage in 10 years. [significant pause] It’s happening!” Look at his eyes.:-)

About #OpenAPS: The Open Artificial Pancreas System

The tool they’re using is the “Open Artificial Pancreas System” cooked up by Dana Lewis and husband Scott Leibrand. As we said here Friday, Dana “has hacked into her CGM (continuous glucose monitor) and her insulin pump and grabbed the data feeds in the devices. Then, using a $35 pocket-sized computer called the Raspberry Pi, she and then-boyfriend @ScottLeibrand (now husband) wrote software to manage her blood sugar better than it’s ever been controlled before.”

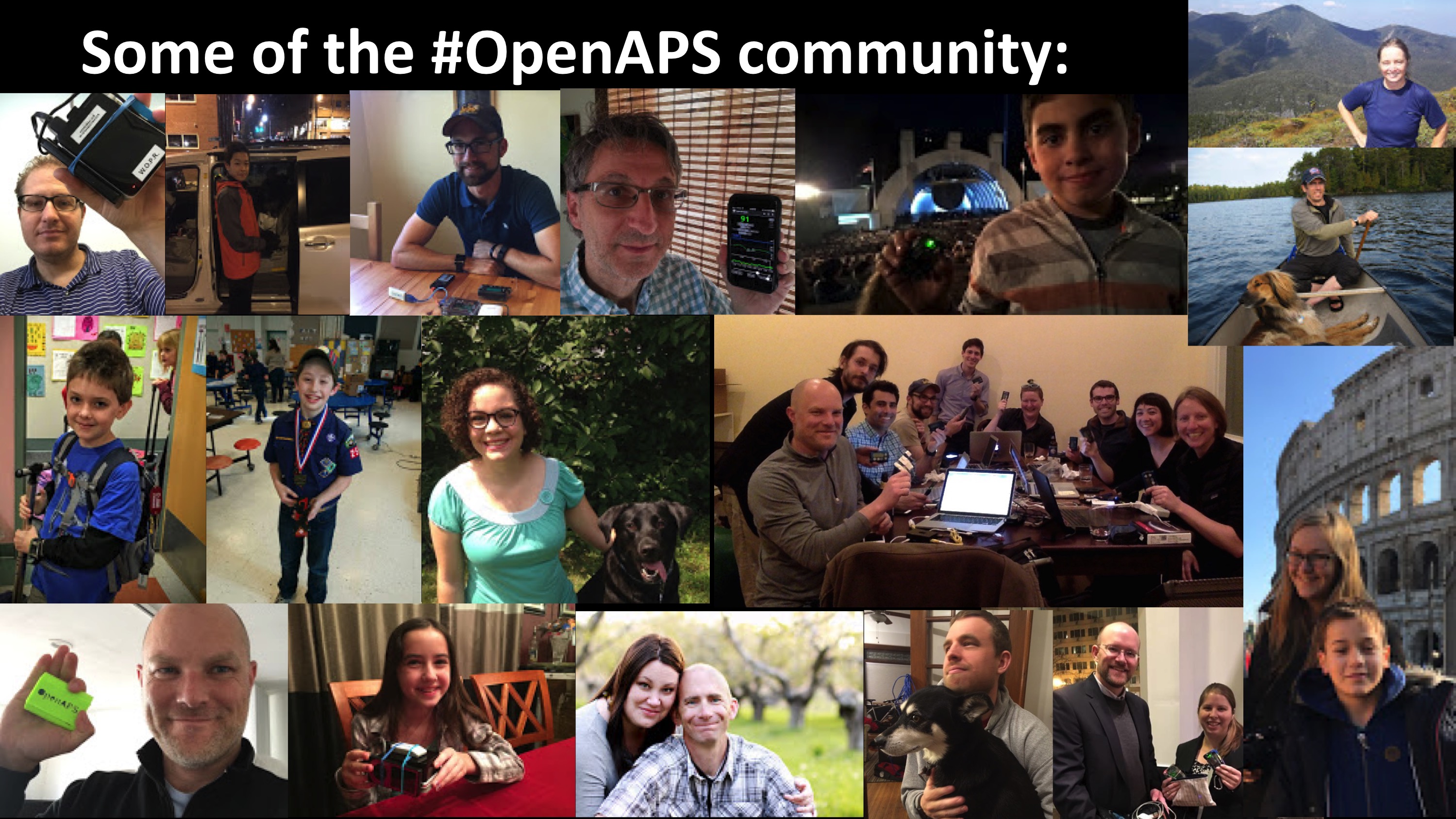

They donated the software to open source, and at least 59 people are now doing it. This event was a gathering of Scott, Dana, and seven other users, to talk about their experiences, both the numbers and their feelings about what it’s like to have their life under better control.

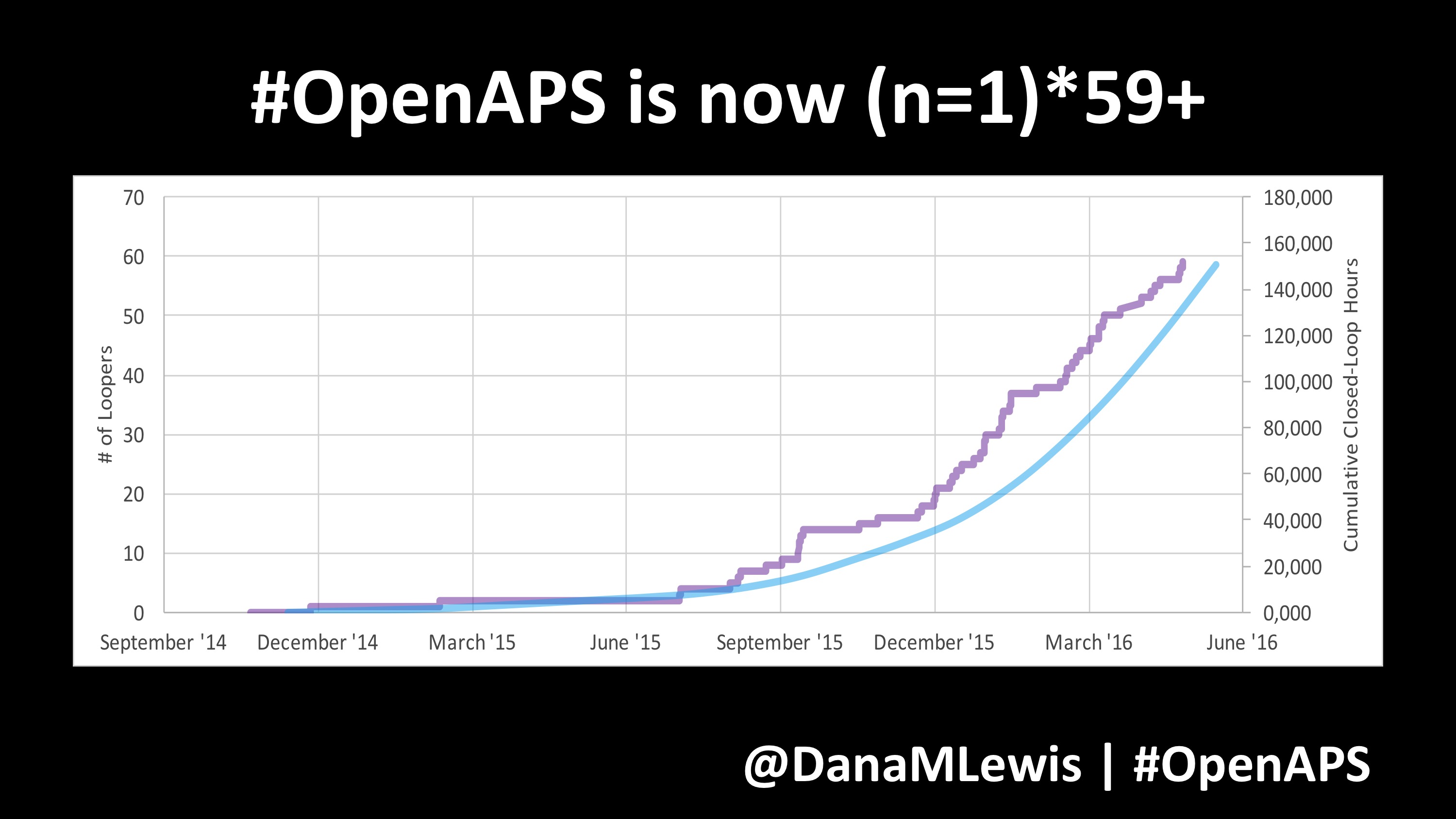

“N of 1 … times 59”

From the beginning, Dana has been careful to say that her results are not a large-scale study – it’s “n of 1,” i.e. just one person doing this, so people shouldn’t draw conclusions from her experience. When others started doing it, they were all responsible about saying “now it’s ‘n of 1’ times 2,” “times 3,” etc. Now it’s been more than a year, and as of this talk, it’s grown to n of 1 … times 59.

Many have chosen to upload their data to the cloud. They’ve logged 160,000 hours of closed-loop operation.

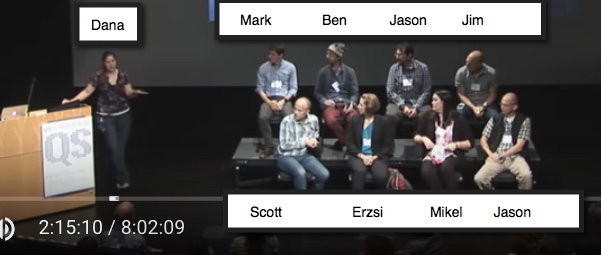

The “loopers” on stage

When Dana and Scott first did this in 2014 the devices were not connected – Scott’s program would read the device data and show her a number to enter into her digital insulin pump. In December 2014 they decided to try “closing the loop” – wiring the devices together. Now they call this “looping.”

Some people think you need to be an IT nerd to do this. No. Here’s Dana’s report of who was on stage, their backgrounds, and when they started looping.

- First row, left to right:

- Scott Leibrand – network engineer – doesn’t have diabetes, supports a looper (Dana) since December 2014

- Erzsi Szilagyi – PhD in chemistry – 9/28/15

- Mikel Curry – exercise physiology & nutrition – 2/1/16

- Jason Curry – forest ranger – supports Mikel

- Second row:

- Mark Wilson – software engineer – 12/28/15

- Ben West – developer, OpenAPS toolkit builder – 9/28/15

- Jason Calabrese – software developer, son Andrew has diabetes – 11/14/15

- Jim Matheson – marketing – 1/25/16

Here, patient experience gets real – at gut level

During Q&A, listen for the feelings some of the newer loopers express about living w T1D (type 1 diabetes) – the constant knowledge that you could die on any day if your disease got out of control. Two of them mention, with mystified expressions, how things they’d learned to assume were permanent might not be.

Listen to how they talk about being able to sleep better, because of the increased confidence they now have. And imagine the experience Jason mentioned of another looper parent, whose child is one year old with this disease … and how they must feel when they go to sleep.

One of my top moments is when the audience asks about safety, and Mikel says she’s had a pump for 15 years and she’s never felt as safe as she does now, after three months of looping.

Listen also for their feelings about hearing, year after year after year, that the industry would give them a product like this in just a few years more. Then, #WeAreNotWaiting.

And look for the spot where they say they can’t do this with the newest devices, because manufacturers removed the commands that make this possible. (Dana emailed: “This is because of a security ‘vulnerability’ that was discovered years ago. But [in our view] the relative net risk of this feature is far outweighed by the net benefit of providing users the ability to control their own devices, as discussed here.”) Can we get to a future where patients have a voice in such decisions? (Who has more at stake?)

The arriving future – as predicted

This is such a signal moment.

- Ten years ago the last chapter of “Doc Tom” Ferguson’s manifesto was titled “The Autonomous Patient and the Reconfiguration of Medical Knowledge.” Sound familiar?

- Our Society for Participatory Medicine defines participatory medicine as a movement in which “patients shift from being mere passengers to responsible drivers of their health.” Sound familiar?

- In 2008, at the Connected Health conference in Boston, internet visionary Clay Shirky said, “The patients on ACOR don’t need our permission, and they don’t need our help.”

Clay’s words snapped back into my consciousness this day, when Larry Smarr said:

“… the incredible inventiveness, the incredible caring that individuals have to make the world different – whether they have got permission or not – that’s the force that is being unleashed.”

Early in his manifesto Ferguson quoted futurist William Gibson: “The future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed.” Indeed, similar projects are proposed for other diseases. Cystic fibrosis is mentioned here, and SPM member Hugo Campos has been mentioned many times on this blog, in print and on NPR for his desire to access the data from the device that’s wired into his heart … to better manage his health, without being limited to what industry provides.

Next month Dana Lewis is presenting a poster at the American Diabetes Association’s annual scientific conference in New Orleans. This is going to be really interesting. Because lives are at stake, and when the people with the problem get access to tools – and their data – they can take their care in whichever direction they want. As a parting thought, here are a few of the lives this project is already touching:

Recent Comments