This is Part 1 of a four part series, introduced yesterday, based on my family’s experience with our mother’s unexpected and dramatic ICU stay and bilateral lung transplant. [Download the Complete Family’s Guide as a PDF]

Even the air in the waiting room of a hospital feels uncertain.

When you first arrive you hesitate at each word, not knowing what is appropriate, who to ask for help, and how or if to break the ice with the others waiting to hear the fate of their loved ones. Each step into the critical care setting creates more questions — entering the ICU, sitting in your loved one’s room, watching as machines are hooked up to her, eavesdropping on discussion about her prognosis and care plan. It feels like you are walking in a foreign land without a guide.

The hospital’s care team rightly centers on caring for the patient. Yet in complex and lengthy scenarios, caregivers can play an important part in a patient’s care and recovery. After all, it’s their lives that will be most affected by the outcome of the decisions made in the hospital. It’s their emotional turmoil that is most palpable in those waiting rooms.

This guide tries to bring light to what can be a confusing and emotional journey for caregivers. It’s based on my family’s own personal experiences over nearly eleven weeks at the University of California San Francisco hospital (UCSF) (almost entirely in the ICU), from my mom’s admission to the hospital, across multiple surgeries, through to her bilateral lung transplant and her eventual (successful) recovery. It incorporates what we learned and experienced through sharing, crying, and praying with the families and friends of other patients we encountered; and conversations with providers and patients at other hospitals about how care is delivered.

This guide barely touches on the emotional rollercoaster of watching a loved one fighting for their life. There is a special uniqueness to each of us and the circumstances we face. I can only offer that it will almost certainly be hard, and caring for yourself is critical to being the best support system you can be.

With this guide I hope to provide you with insight into the written and unwritten rules of critical care — and help you navigate them through the experience. There is no single best path to handling such a unique journey. This document is one source of information — and could be too much information or too hands on for your situation. Your context and own perspectives should guide you in how it fits (or doesn’t) in your story.

We expect this guide to be interactive and will seek to improve it through the input of the community. Please use the comments section to share your own stories about navigating this path.

Navigating the Chaos

Everyone’s story for how they get introduced to the critical care unit is different. Some know they are heading there, while for others, it is a surprise. In our case my mom entered the hospital for a medium to high risk procedure — a lung biopsy to try to diagnose her Interstitial Lung Disease. After what appeared to be a smooth procedure and initial recovery, she developed ARDS (Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome). Within three days of her initial procedure she was on a ventilator and unable to speak for nearly her entire stay at the hospital.

It soon became clear she would require a lung transplant in order to recover. Luckily, we were at UCSF which has an excellent transplant program. Others started at different hospitals and came to UCSF when it became clear a transplant was their only hope.

Where you are provides some context for how you should engage – and what kind of additional help or support you might need. For example, the quality of the hospital you are in and its expertise in what is happening to your loved one may impact how often you decide to be at the hospital or the level of detail in the questions you ask. While everyone’s situation is unique, one of the first things anyone can do upon entering a critical care setting is to try and understand the structure and surroundings in which you and your loved one are now entrenched.

Who’s Who in the ICU – An Overview

Each hospital will have its own structure of doctors, nurses, and specialists – and several types within each of these categories. This is particularly true once you are taken into an ICU.

| Medical – General | Medical – Specialists |

|

|

| Therapists | Support / Other |

|

|

At UCSF we interacted with nearly all of the roles above, and it became quite overwhelming at times. We had our medical specialists (cardiothoracic surgeons, pulmonologists, transplant surgeons) who were technically in charge of my mom, but they would coordinate with or even defer to the ICU team (intensivists etc.). There were also many at various stages of training (fellows, residents, medical students) supporting or learning from these groups.

The team outside of the doctors was larger and as essential to care. Therapists had specialized responsibilities related to key elements of care. A small group of nurse practitioners acted as the central point of continuity. The nursing team spent the most time in the room caring for my mom.

To make it even more confusing, each of these roles will have rotating schedules. Some work a standard week, others three shifts per week (which are usually 12-13 hours). In certain roles, each person is on call/service for a week, then won’t be back for 4-8 weeks.

Nurses and the Nurse Practitioner – The Front Lines

In most ICUs nurses will cover one or two patients at a time. They are the front line of care for your loved one and the ones you will most interact with if you are spending significant time in the room. They have a lengthy set of responsibilities. These can include:

- Administering medications

- Responding to alerts (i.e. alarms going off in the room)

- Performing regular checks of a patient’s medical systems

- Caring for wounds

- Cleansing

- Drawing blood

- Managing the IVs that administer nutrients or medicines

- Understanding what the patient is feeling and experiencing

- Coordinating with doctors and specialists

- Responding to the patient (e.g. call button)

Depending on whether it’s the day or night shift, what is occurring and how many patients a nurse is managing, the ICU nurse might be in the room with your loved one from 3-8 hours over the course of a 12 hour shift. For caregivers, these nurses are important people to establish a relationship with even though there will be many of them throughout the patient’s stay. In an average week, nurses work three twelve hour shifts. So a patient might see between 5-10 nurses during the week. Over the course of about three months we had ~50 different nurses.

In my family’s experience, the greatest continuity across the weeks came from Nurse Practitioners (NP) who were associated with the transplant team. Nurse Practitioners would visit my mom 2-3 times per day during their shift and they connected with the rest of the medical team. They also could make decisions regarding changes to medications and other normal procedures.

The Elusive Doctor

By comparison, doctors are fewer in number and seldom available directly to you. Every morning after the first shift starts, the doctors and some combination of nurse practitioners, residents, fellows, and nurses “round” on each patient to discuss their situation and plan. Sometimes multiple groups will round on the patient. During our most extreme times we would see the pulmonologists, ICU team and surgeons separately. In times of stability, this can be the only time you see “the doctor” during a shift or even the day. Rounding at night was a smaller ordeal with sometimes only a single resident, attending physician or nurse practitioner stepping in to review the patient.

Often the rounding group gathers outside of the room to talk about the patient; reviewing test results (i.e. labs), charts and images and discussing their care and plan. Some doctors welcome the patient’s caregiver to sit in on rounds, others seem more resistant to it. Then the group walks into the room to talk to the patient (if possible) about how she/he is feeling and what is happening, review questions and communicate key procedures, changes to plan, etc. In some settings rounding and the patient interaction are done together in the room. While we likely saw more than 20 doctors during my mother’s time in the hospital, the majority of care decisions were made by between 5-7 doctors.

A wide range of specialists will likely visit your loved one during the day as well — guided by the care plan of the doctors and coordinated with the nurses. My mom saw a respiratory therapist twice a day for breathing treatments; and often saw a speech, occupational and physical therapists as well as a nutritionist. In her context much of this therapy was critical in keeping her strength up — first so she would be eligible for a transplant, and then during the most important recovery phase after the procedure. Most specialists are only available during the day Monday through Friday. If you miss a session — whether due to a procedure or scheduling challenge — it can feel like a massive missed opportunity for continued improvement.

Tips to Navigating the ICU Staff Structure

|

Communicating with these different providers can be challenging. Communication is normally restricted to in-person discussions or through a nurse’s page. Phone calls are typically one way – they call you for when something is needed. Email, text and other messaging is not normally an option. If you want to speak with a doctor, you will likely need to be there when she stops by or explicitly request a meeting or call. With some research you may be able to discover their email addresses, but direct contact information is rarely provided to you.

Understanding these different roles and how and when they work together helps ease the frustration limits on communication can create at a time of enormous stress.

Getting To Know Your Surroundings

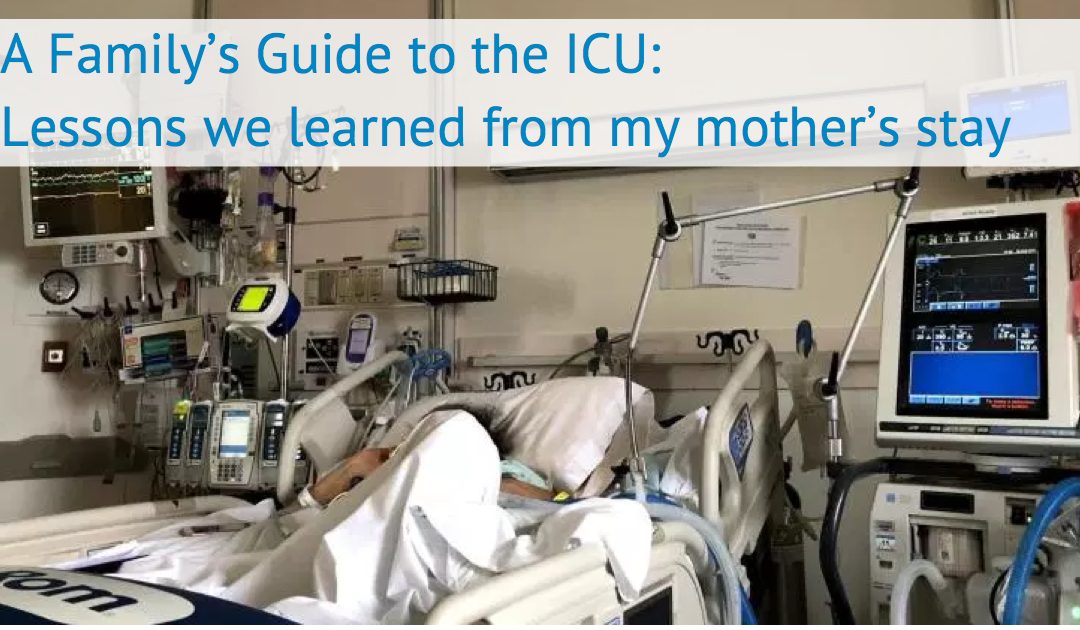

It’s shocking to walk into an ICU room for the first time. You’re in a place with serious consequences and your loved one is hooked up to machines that look like they are twenty years old. Things are constantly beeping. Patients are connected to machines that help them breathe, process their blood (e.g. dialysis, ECMO), deliver medications, closely monitor vitals, and the list goes on.

It’s shocking to walk into an ICU room for the first time. You’re in a place with serious consequences and your loved one is hooked up to machines that look like they are twenty years old. Things are constantly beeping. Patients are connected to machines that help them breathe, process their blood (e.g. dialysis, ECMO), deliver medications, closely monitor vitals, and the list goes on.

One of the most disruptive aspects of the experience is alarms constantly going off. Alarms are supposed to represent an event that requires attention from the nurse, such as an escalating or declining blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, or oxygen saturation. Initially, you may feel like nurses are not reacting to problems (especially when they are not in the room). Yet studies have shown that more than 90% of alarms in an ICU setting are either not medically important or false — so it is easy to see why they are not perceived urgently by the staff. Depending on how long a patient’s stay is, you will likely become more familiar with what is monitored and what is normal for your loved one.

You’ll also notice a computer that’s inside and/or outside the room. The hospital staff use this to look up information about your loved one (procedure notes, imaging, lab tests, medication), to scan in medications and treatments, and capture other important insights about their progress. If the screens look like they are 20 years old, it’s most likely because they are.

Some hospitals will have additional consumer apps that let you see a subset of the patient’s data such as real-time lab results (see screenshot of one common one call MyChart). However, these apps are few and far between and lack much information.

Some hospitals will have additional consumer apps that let you see a subset of the patient’s data such as real-time lab results (see screenshot of one common one call MyChart). However, these apps are few and far between and lack much information.

You also may notice that your loved one is not alone. Most ICUs group between eight to sixteen people to an area, often divided by curtains and/or glass dividers. While the lack of privacy might be jarring, the ICU is set up like this so that providers have more visibility to patients and can respond faster to emergencies.

Emergencies will happen that cause a dozen plus staff to assemble around a single patient to intervene. When this happens to your loved one it can feel surreal. If you are spending a significant amount of time in the room, you’ll almost certainly observe such an event somewhere nearby in the ICU and it’s hard to know what to do in such an event. In my experience at UCSF, expectations for caregivers varied by the nature of the emergency and based on the staff that was there. Sometimes they wanted us to stay put and not leave the room so we didn’t disturb what was occurring elsewhere, and in other cases they asked us to exit the ICU so they could prepare for a procedure. The nurse in charge of your loved one during that shift is the best source of direction in most of these real-time scenarios.

In Part II we will examine the why and the how of the ICU – why certain rules are in place, how they view your presence and your role in supporting your loved one’s care and hopefully recovery.

Tips on Navigating the ICU Environment

|

Recent Comments