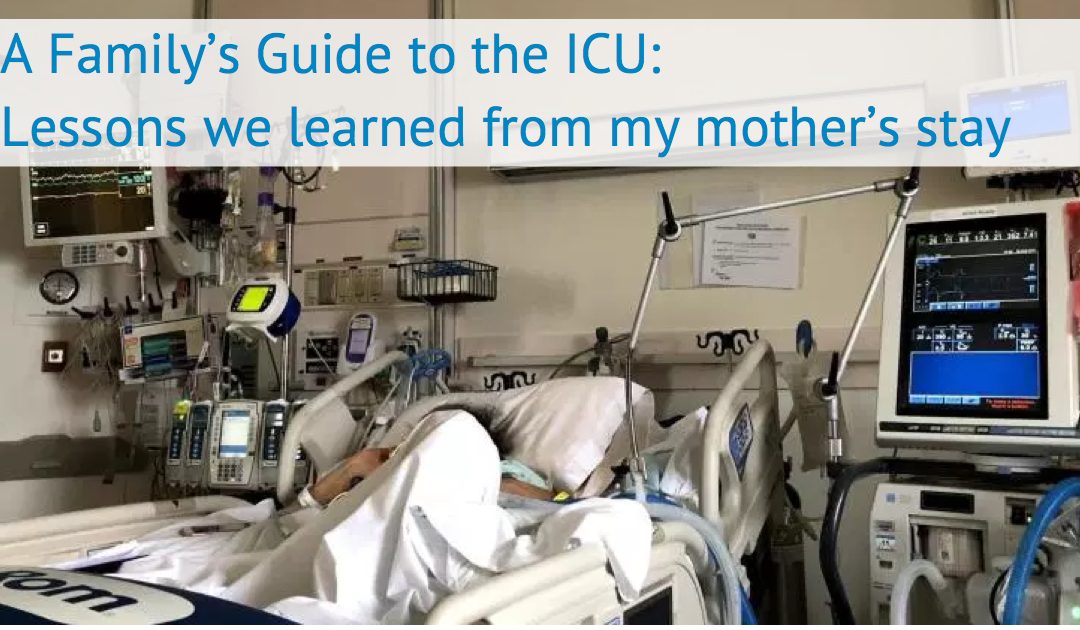

This is Part 2 of a four part series, introduced Monday, based on my family’s experience with our mother’s unexpected and dramatic ICU stay and bilateral lung transplant. [Go to Part 1]. [Download the Complete Family’s Guide as a PDF]

After the first few days in the ICU, your anxiety and shock might begin to morph into confusion about why things are the way they are. You will have many questions about what role you and your family should be playing in this new environment.

Your Presence

Most ICUs will have an established policy for visitation — who can come into the ICU, how to ask if the patient can have visitors, the visitation hours, etc. Many of these rules are put into place for a reason. Most patients in the ICU are immunosuppressed, which means their immune systems are weakened and less resistant to infection. Hospitals tend to favor short visits to provide patient support, suggesting that creates more rest time for recovery.

Some ICUs have more restrictive visiting hours than others, and some discourage family from being there too often. At first glance, the rationale for such recommendations seems straightforward. In addition to the above, families get emotional and they can distract nurses from giving patients the attention they need. Yet even if this was true on average (which recent research suggests is not the case), it’s not automatically true in your individual situation.

The premise that caregivers are distracting offers an incomplete, overly generalized, and slightly disingenuous view of the situation. What if the patient has difficulty communicating because English isn’t their first language, or if they don’t trust strangers easily? It also fails to fully value the power of actually knowing the patient. What is their tolerance for anxiety or pain? How do they react to certain circumstances? What does their gesturing mean when they can’t speak or write?

I also believe that one of the drivers for limiting visitors is related to the staff not wanting to have someone constantly looking over shoulders while they do their job. While this is understandable at a human level — few of us would welcome that scrutiny at our own workplaces — when the stakes are life and death of your loved one it feels irrelevant.

Hospitals have rules in place because they perceive they help to provide the best care possible to all the people in the ICU. However, as a caregiver, your objective is to advocate on behalf of one patient. You have a population of one that you are fighting to give the best chance possible. These objectives are not often in conflict and it is in your interests to maintain a respectful environment. But where the hospital perceives them to be, it is their responsibility to manage that, not yours.

Your Role in Your Loved One’s Care

Depending on your life situation, time, desire, knowledge, personality, you may want to be there all the time, visit strategically, or perhaps blend the two. You might be OK simply knowing the details of your loved one’s medical conditions and treatment or being there simply for emotional support, or you might want to choose to be more proactive in care and recovery.

Everyone’s circumstances are unique, however, here are a few points of engagement that you need to agree upon as a family going into and during your time as a caregiver in the ICU.

Decision Making – Who’s the Point Person

There are a great deal of decisions that need to take place in an ICU, and it’s important to have a point person for helping a patient make important medical decisions — especially if the patient is incapacitated.

In a perfect world, you’d have this figured out before even entering the hospital but that was not our situation. In our case, we were in the waiting room at UCSF with my mother, filling out the advanced directive information (who decides if the patient is unable to) as an afterthought. Our approach was haphazard. We barely filled out the form even though lung biopsies (the procedure she was having) had a serious complication rate of between 5-15%. We had not substantively discussed the concept of the lung transplant and spent no time discussing what to do if things went poorly.

Even though I was listed as the responsible party, it was clear I would never make such decisions without broadly consulting and having consensus from our family. Yet not speaking directly about the possibilities ahead of time with my mom created repeated stress and sometimes delayed our decision making and consent for certain medical procedures. These delays could have been costly in her outcome, so have these conversations before situations become dire if possible.

Ongoing Care and Emotional Support

Once my mom’s initial complications occurred we knew we wanted someone from the family to be available to her as often as possible. We felt this was critical to support her emotionally given who she was as a person and the unexpected set of events and uncertainty of what would happen next. As we spent more time in the hospital, we also came to believe being there ensured the best chance for a positive outcome for my mom. We saw that we helped provide emotional support, pushed her to do more to help herself, and ensured the care team acted on accurate information about her conditions, progress and emotional state.

For my mom, mornings tended to be the most difficult part of the day. She had more discomfort, felt more anxiety and was generally less engaged early in the morning. We chose to be there, especially during those tough mornings, to reinforce that we loved her, even if it was at conflict with her wishes in the moment. Being there to push her to get more active and letting her be frustrated with us instead of the nurses might not have been what she wanted at the moment, but it helped her do more in enabling her recovery.

Also we observed that certain medications meant to help her ward off pain or anxiety actually made her lethargic and less motivated. Often, helping her struggle through a few minutes of pain or anxiety helped reduce her reliance on these interventions (which meant she was more awake/alert for all forms of therapy).

Providing this support can drain caregivers. You are there to be sensitive to your loved one’s pain, needs, troubles, worries and concerns. Yet, it becomes clear that supporting him or her often means being insensitive – forcing them to work through pain and discomfort to participate in their own recovery. Many times patients go through actual delusions or hallucinations in the ICU. They can also develop skewed perspectives on who amongst friends and family is there for them and caring for them the “right” way. It can be hard to handle that unfair or inaccurate judgement from your ill loved one. It’s important to remember they are using everything they have to fight for life and what they may be expressing in a moment is not necessarily reflective of how they feel or what is happening. Making sure you have a support system to help you manage through this.

Pushing the Patient – Sometimes Love Hurts

Years of medical research shows the correlation between medical outcomes and the amount of activity pre- and post-procedure. The days of just wanting patients to rest in bed are a distant memory. The entire team constantly reinforced to my mom and my family how important it was to maintain her strength if she wanted to remain on the transplant list and recover well from the eventual surgery. As a result, we were constantly focused on her therapy. The Physical Therapy (PT) and Occupational Therapy (OT) teams at UCSF were exceptional at pushing all of us on this front. Yet they could only come maybe once or twice in a day. That created a sense of urgency to get the most out of those sessions, to ensure we never missed their windows, and for my mom to do her ‘homework exercises’ as much as possible between sessions.

Our role was to help her with this so she could build her strength. We acted as the “bad cop” to make sure she did her assigned exercises, and constantly encouraged the breathing, physical, occupational and speech exercises that would make her stronger. She didn’t always like it, but we believe it helped her recovery in the end.

A Day and Night Difference

There is a well known phenomenon that care levels change between night and day shifts, between weeks and weekends, and even between different times of year. Yet because of liability, no one at the hospital can directly address which times are more dangerous. The fact is, sometimes the right care decisions are wrong simply based on when they are occurring.

In our case, after a few weeks in the ICU, it seemed obvious staff members were over- medicating my mom at night. In certain cases the plan was to wean her down or off of a particular set of drugs at night and we’d return in the morning to find it at the same levels or even higher. In other cases, certain medications administered selectively at night would result in her sleeping until noon and missing important morning activities such as physical therapy or her doctors doing their rounds. We were still early enough in her journey so we were hesitant to say anything, but were increasingly contemplating doing so. Then, an abrupt experience made it clear that the quality and reliability of care at night was not as good as that during the day – and that was the deeper concern.

After some small but steady improvement to her breathing (she was on a trach collar with ventilator support at the time) she started having an elevated heart rate and her oxygen levels dropped. During the night she had more and more trouble and her oxygen level dropped dangerously low. All of a sudden doctors and nurses poured into her room. They were not her normal team but residents, nurses, and nurse practitioners from other departments. It was difficult to fully discern who was in charge and who was making the decisions. Nurses not assigned to my mom more freely offered their opinion on what should happen. Some of them were right, others just distracting. The resident who ended up being in charge nervously consulted with an attending physician from another floor, called the doctor on my mom’s team who was on call, and intermittently directed the activity.

The next day through eavesdropping on conversations and reading body language it seemed like the actions taken were most likely the right ones. However, it was also clear that the decision making process, expertise available, and general control of the situation was much more subject to error because it had happened at night. There simply wasn’t the same number of people or depth of experience available during the night shift.

Seeing this recast our view of medication dosing and all other activity in terms of days vs. night. If slightly over dosing the patient resulted in a lower chance of an emergency occurring at night it was likely worth it. It’s clear certain doctors and nurses had the same philosophy but it was not openly articulated. A similar phenomenon occurred between staffing levels on weekdays vs. weekends. As the weeks went by we learned to hope for steady progress in health metrics (strength, walking distance, breathing, etc.) during the week; our goal for the weekends became much more modest — just not to lose ground.

Overall, it gives one some appreciation for how complex and subtle medicine and critical care can be. The right actions during the day can be the wrong ones at night. It’s not a reason to simply give up and not pay attention, but it does reveal that it’s important to understand context before making or conveying critiques. Trying to understand why certain actions would happen can help mitigate your concerns. How you perceive the correctness of actions, risk, and excellent care will certainly change over the days, weeks and months.

Tips on Caregiver Engagement

|

Over time you’ll pick up on these nuances and even who on the care team is more competent or engaged than others. This is also important intelligence when determining how much attention you pay during various stages of care. For example, as we got to know the various nurses, who was covering mom greatly impacted our presence and actions. It would affect when we would be at the hospital, if we would stay overnight, what questions we would ask after a shift and more.

In Part III we will discuss your role as an advocate for the patient, potential ways of engaging with staff and how to help support the continuity of care.

Recent Comments