For most people, their impetus to be actively engaged in healthcare comes from an experience with serious illness—either their own or a loved one’s. My journey into participatory medicine began during my internal medicine residency at Boston City Hospital, a public urban hospital, in the late 1980s. While there, I had a number of realizations that led to my passion for participatory medicine.

The first was that educating patients and communicating with them effectively pays big dividends in improved health behaviors and outcomes. It is the most cost effective intervention we can offer. Moreover, this only happens in an environment of mutual respect. In almost every patient, there is something to be treasured and respected. Hopefully, they feel the same about us.

Next I realized that so much of what we do in healthcare is information management. An extraordinary effort is invested into locating, organizing, recording, and regurgitating information that is used in patient care. More on this later.

Finally, patients only see us (the healthcare system) for a small fraction of their lives. The rest of their time they are home (or in the case of many of my patients in those days, in shelters and on the streets). Therefore, no matter what we do in the office or in the hospital, it all falls apart if healthy behaviors don’t persist.

Because of my interest in information technology, I felt that I should cultivate that interest to hopefully improve the way we manage patients. I pursued a fellowship in clinical computing, often called medical informatics. I was fortunate to do this at Beth Israel Hospital (now Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Beth Israel was one of the first hospitals (since the 1970s) to use e-mail extensively for internal communication (I was there prior to the widespread use of e-mail). As part of my work developing and implementing clinical systems, I wanted to improve the process of coordinating care for patients to prepare them for discharge from the hospital. E-mail seemed to be an important communication tool in the hospital, and I suspected that it was mainly used for communication about patients. My mentor doubted that, suspecting that it was mainly used for administrative and social messaging. I subsequently did a study that revealed that a plurality of hospital e-mail use did in fact concern patients.

As part of my role at Beth Israel, I saw patients in a primary care practice. At about the time I started building my practice in the early 1990s, Beth Israel had entered into a joint venture with a health plan, so it could provide low-cost health insurance to its employees. The plan was obviously very popular, but it required that its members see physicians that were part of the hospital network. Since I was accepting new patients, many employees became my patients.

Because they were employees who were accustomed to using e-mail, it was very natural to communicate with these patients using e-mail. By the time we connected the hospital e-mail system to the internet outside the hospital, I was already becoming comfortable with its use in clinical care. Moreover, I found that when used appropriately it reduced communication barriers with patients and augmented our relationships.

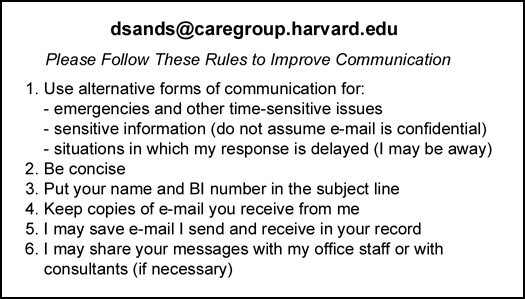

Over time, I developed best practices for its use, and in 1998 I co-authored the first national guidelines for the use of e-mail in clinical care for the American Medical Informatics Association, and later augmented these with community input for the Massachusetts Health Data Consortium.

Over time, I developed best practices for its use, and in 1998 I co-authored the first national guidelines for the use of e-mail in clinical care for the American Medical Informatics Association, and later augmented these with community input for the Massachusetts Health Data Consortium.

One of my teachers at Beth Israel was Warner Slack. In the 1960s, Warner was developing program that were among the first interactive computer-based interviews for patients, which asked patients questions and later attempted to diagnose simple medical problems. He later wrote that patients were the most valuable but underutilized sources of information in healthcare. This profound bit of wisdom, still being quoted 40 years later, stuck with me. Warner encouraged me to pursue my patient-centered work.

Warner introduced me to Tom Ferguson, the pioneer of consumer health informatics, and we became fast friends. I was eventually drawn into a close-knit circle of Tom’s apostles that became known as the e-Patient Scholars Working Group. In 2009—three years after Tom’s death— we went on to organize the Society for Participatory Medicine to realize Tom’s vision.

At Beth Israel I also worked with Charlie Safran, David Rind, and others to develop the OMR, an online medical record for use by providers. We put computer terminals (later computers) in all examination rooms. I found that using the OMR during patient encounters was most effective when I could turn the monitor to share their records with them. This had the immediate effect of demystifying the record and the patient’s own health information. Together, my patients and I were able to review the impact of lifestyle changes—both good and bad— and medical interventions on their physiologic parameters. This information was empowering to my patients.

After we linked these exam room computers to the Web, I developed our first clinical portal to organize the wealth of web-based resources for physicians. From its very first iteration it included a section containing patient educational resources for two reasons.

- For one, I wanted to raise clinician awareness of the plethora of patient-centered references on the web, and wanted to encourage my colleagues to share these links with their patients.

- In addition, I then had a collection of sites that patients could access from anywhere. In fact, I adopted a policy of inviting my patients, as they waited for me in the exam rooms, to peruse health-related websites and to print or write down what they found interesting and discuss with me any questions they had. This sparked some interesting exam room discussions, and is a practice I continue to this day.

After reading survey results from CyberDialog (now Manhattan Research) and Harris Interactive, and later Pew Internet and American Life Project, I realized that many patients were probably getting health information from the web, but many never mentioned it to me. A few years earlier, in 1993, David Eisenberg, one of my colleagues in General Medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess, had published a landmark study in the New England Journal of Medicine that found that 1/3 of patients used complementary or alternative health methods but almost 3/4 of these never discussed it with their physicians. He suggested that this become a part of all of our discussions with patients.

I extrapolated to the use of health resources on the Web and began a practice of asking every patient I meet whether they used the internet, if they had ever used it to obtain health information, and which websites they found useful. This conversation helped my patients understand that, unlike some of their physicians, I welcomed discussions about information they might find on the Web and in fact encouraged them to search. Through this, I also learned about new websites from my patients and, after reviewing them, I added them to the patient resources section of our portal.

I learned from one of my early mentors that most physicians, especially those in training, had difficulty admitting when they didn’t know an answer. Although this is true when communicating with other health care providers it is especially seen in discussions with patients. Many physicians feel that they have to maintain an aura of medical omniscience, something ingrained since medical school.

This information asymmetry, where the physician knows everything and the patient knows nothing is comfortable to many, but it felt burdensome and dishonest to me. I felt liberated when I started admitting to patients when I didn’t know something and, rather than leaving the exam room to look things up, I found we could research things together online.

This was a much more satisfying approach to both me and my patients. Even more, by recognizing that patients have access to health information and could be intellectual partners in their care—which they should, since they are not only experts on themselves but have the most at stake—I found that time in the office could be much more productive. We thus moved from a relationship based on information asymmetry and paternalism to one of information symmetry and patient autonomy and engagement, which benefits both me and my patients.

In subsequent years I worked with John Halamka, David Rind, and others to develop PatientSite, which went live in 2000. PatientSite is a secure web portal that encourages secure e-messaging between patients, physicians, and other members of the care team. The site also provided patients with information so they could better manage their health, permitted patients to request appointments and perform other administrative functions. Most importantly, PatientSite allows patients to see most of their records online, and every month 16% of our patients do just that, providing them the ultimate in personalized health information.

This type of access to one’s health information and healthcare team is ultimately empowering to my patients. One of my patients, a retired minister disabled by diabetes and advanced neuromuscular disease wrote me that:

“I have a lot of medical issues. This … system has left me feeling comfortable and in good hands! Otherwise, I would feel as cold, depleted, and alone, as the lifeless tree in my front yard in the deepest of winter!”

My patients are no longer dependent on me to share what I wish to share at my convenience but creates a more level information playing field. Their healthcare team is still available to answer questions about what they are seeing and it doesn’t mean that we don’t communicate information an interpretation to patients, but it seems to me only just.

I am taking a piece of your body to run a test, so you have a right to know what happens to that specimen as soon as possible—and in most cases it’s just as soon as the result is available to me.

If we can track packages and anticipate the time of their arrival online through FedEx and UPS, why can’t we track and receive our test results the same way?

So my path to being a Participatory Medicine advocate does not come from experience with serious illness but is born from lessons learned as a physician and as a health care information professional. It also derives from long discussions with colleagues, all of whom are now involved in the Society. But it just makes sense on so many levels, and now more than ever.

Our inefficient and overstretched healthcare system is struggling with an aging population and an increasing burden of chronic illness, while families are coping with helping to manage the healthcare of their aging parents. It is apparent that the only way out of this hole is to engage people as partners in their wellness and healthcare. This requires a cultural change, among both individuals and healthcare providers. This can only occur through early and continuous education of citizens and physicians. Connected technologies, which provide unprecedented opportunities to lower the barriers to patient engagement can be an important tool in this cultural transformation.

One lesson that I share with physicians is that Participatory Medicine is not just something that we do for patients. It’s something we do with patients and that benefits both patients and physicians. I passionately believe that the status quo in healthcare is unacceptable. Participatory Medicine is necessary to the future of healthcare delivery.

It’s about time you came out from the shadows. :–)

I’m getting tired of people saying “Danny Sands, primarily famous for being e-Patient Dave’s physician.” Who’s one of the early members of this working group? Who’s the one who said to me, when my life was falling apart, “A good friend of mine [Gilles Frydman] has this group of cancer listservs” prescribed ACOR.org to me?

History and origins are so important. Thanks.

I think the universe had great plans in mind when it put the two of you together in an exam room!

Excellent post, thank you.

Lovin’ your level of engagement with this emerging conversation!

Danny, I thought I knew all about you and I didn’t – doubly, triply impressed and honored to be part of the story. Thanks so much for sharing!

For more insights on “Why Participatory Medicine?” and the challenges ahead, it’s super-pertinent to mention that the Society of PM (co-chaired by Danny & eP-Dave) has just launched the Journal of Participatory Medicine at http://jopm.org. Diverse perspectives are offered from thought leaders Esther Dyson, George Lundberg, Richard Smith, co-editors Jessie Gruman and Charlie Smith, Gilles Frydman, Peter Frishauf, Kate Lorig, David Lansky, Amy Tenderich – and many others.

Articles pose scores of Open Questions in this nascent field, highlighting the research that’s required and the varieties of evidence sought to legitimize and ensure the effectiveness of the movement.

Participate!! See the journal’s Call for Submissions, follow @JourPM, and tweet your ideas via #WhyPM.

Postscript: Aside from the futuristic journal which we hope will define and amplify PM, noted in the comment above, I wanted to point to a bit of Danny’s history as email doc. This was an article published in 2001 in the web magazine Praxis Post (the culture of medicine; partially recreated on my personal web site), which I co-founded and which was edited by Ivan Oranksy, now of Reuters Health. Danny was truly a pioneer on the tech side of of the doctor’s office, and here’s the evidence!

Danny,

Thank you for sharing, indeed! Very nice post coming from a healthy clinician.

I thank you for writing about Warner Slack, who with Tom is one of my personal heroes. Warner was one of the only physicians who, in 1996, understood the idea behind ACOR and became one of its first board members.

I really enjoy reading your rationale for supporting and promoting the concept of participatory medicine. But your explanation of the meme remains very much doctor centric as it appears in your conclusion: “One lesson that I share with physicians is that Participatory Medicine is not just something that we do for patients. It’s something we do with patients and that benefits both patients and physicians. I passionately believe that the status quo in healthcare is unacceptable. Participatory Medicine is necessary to the future of healthcare delivery.”

I agree with the last sentence but as the one who proposed the term Participatory Medicine to the founding group of SPM in Feb 08, I want to remind you of my definition at that time, and one that I’ve promoted ever since: PM refers to patients participating in their care (with whoever is needed or available at any point). In other words, clinicians are not required to set participatory medicine in motion. When 2,000 cancer patients discuss new treatments, side effects or many other topics of interest to them, they are “doing” participatory medicine, filling in the void in care that the modern health care system has created and they do so without the presence of any clinician. As quoted in the preface of our White Paper:

Unlike what happens in most medical settings, medical care for anyone suffering from a life-threatening condition is best seen as a continuum not as a series of disjointed episodes of care. Patients that are involved in participatory medicine have all understood that fact and they manage their condition accordingly, saving themselves and society real expenses and transforming the level and quality of care they receive as well as making real positive changes in their Quality Of Life.

This remains hard to accept by many physicians but Tom saw the writing on the wall more than 30 years ago and lived his life as the original theorician of participatory medicine, while living with cancer for 15 years! One of his fantastic original ideas is the reverse triangle explaining the new paradigm of medicine:

Danny, great post. No arguing the fact that participatory medicine is strengthened when a person (patient) finds enlightened medical professionals to work with, along with many many others. And to the extent that people (patients) are soaking up not only information, but attitudes and approaches to their health challenges, the influence of a caring and energizing professional can be magnified. Dialogue is more productive when medical professionals can adopt a “patient-centric” approach and patients can appreciate the value of many “doctor-centric” ways of thinking/behaving.

Hi Jon, good to meet you.

We (all, here) couldn’t agree more that participatory medicine is a two-way street, requiring (even demanding) changes in the role of both ..um.. participants. Truly so.

I left a comment yesterday, just saying thank you. It did not make it, apparently. So I repeat my thanks to Dr. Danny Sands for this post. It is very stimulating to see someone from the field with such ample experienced confirm what I as president of ICMCC have been stressing in Europe for the last couple of years, the importance of education of both patients/citizens and caregivers (e.g. see my congratulations to the PM Journal.

The link to the congratulations blog: http://blog.icmcc.org/2009/11/01/journal-of-participatory-medicine-congratulations/

Bonjour , Super blog ! Je traite du m?me sujet sur mon wordpress. Je me permettrai de reprendre de votre texte. En vous citant bien sur et si vous le permettez. Je traite aussi de sujet comme mutuelle hospitalisation ou comme forfait optique. Merci, Ethan