Stop what you’re doing, as soon as possible, and spend 20 minutes watching this. It’s the most powerful short talk I’ve ever seen about health care.

Our e-patient white paper is titled “e-Patients: How they can help heal healthcare.” In this talk from March’s TEDx Dartmouth, Al Mulley, MD, MPP doesn’t use the word e-patient, but he asks directly: who can fix health care? “Doctors and nurses can’t; policymakers can’t; even presidents can’t,” he says. Guess who that leaves.

(Email subscribers, if you can’t see the video, click to come online.)

TEDx events are smaller, independently organized events in the TED family. Dartmouth produced one last March, and one speaker was Al Mulley, Director of the new Dartmouth Center for Health Care Delivery Science. Yes, the science of delivering healthcare – think evidence-based medicine, expressed in what their site calls “an aggressive collaboration” across all of Dartmouth’s schools and the Dartmouth-Hitchcock hospital system.

Mulley was a founder of the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making (FIMDM), about which we’ve written here several times. FIMDM is in turn a prime sponsor of Gary Schwitzer and team’s Health News Review, about which we’ve written much more. Both are highly participatory – they’re all about patients being better informed and empowered.

Al has a way of taking an immense amount of information and conveying it quickly and clearly. People have spoken for hours and not delivered this message so well.

Decision making in uncertainty – “the fog of healthcare”:

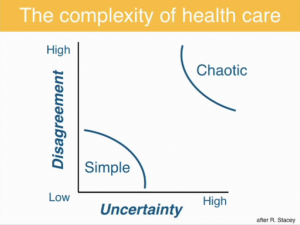

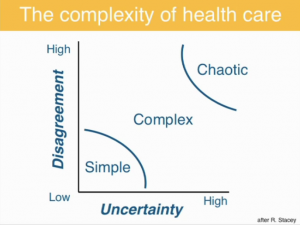

We’ve often written about SDM (shared decision making). At 9:45 Mulley shows a “Stacey Diagram,” adapted from UK change management guru Ralph Stacey. He’s just reviewed how there are Here’s how he describes it:

<– Illustration at Left: “When uncertainty is low, about getting B if you do A, and disagreement is low about how good or bad B is, decision making and execution can be simple.” [Bottom left corner]

<– Illustration at Left: “When uncertainty is low, about getting B if you do A, and disagreement is low about how good or bad B is, decision making and execution can be simple.” [Bottom left corner]

“When uncertainty is high, and disagreement is high, decision making and execution can be chaotic.”

Then the slide at right: “Most of life, and certainly most of healthcare, is in this zone of complexity.” And here’s the crux of SDM done right: “It’s the profession’s job to reduce the uncertainty as much as possible … It’s not the profession’s job to try and get people to agree…to get two men to agree about the tradeoff between urinary function and sexual function … two women to agree about how bad it is to live without a breast, how bad it is to live with the prospect of a recurrence.”

He cites the evidence that when patients are fully informed about risks and benefits, they tend to choose less treatment.

The climax of the reasoning – “Who can fix health care?” – is in the slide around 16:00, which builds to this conclusion:

Patients must shape the capacity of the health care system by revealing their preferences.

There you have it: patient centered care, customer-centered thinking, whatever you want to call it. If we don’t educate ourselves – if we don’t ask doctors for all the pros and cons – the system will evolve in the direction its investors like: more sales, aka higher costs. And wait til you see the ultimate impact, in his closing anecdote.

This TED talk gets my personal “standing O” for its clarity. Plus, it shows that participatory medicine is essential to fixing healthcare. The definition from our society’s website:

Participatory Medicine is a movement in which networked patients shift from being mere passengers to responsible drivers of their health, and in which providers encourage and value them as full partners.

If we continue to expect the industry and Washington to fix healthcare, as we’ve been doing for decades, the outcome is unlikely to change. It’s time for patients to step up and ask: “Is this what’s right for my child? Is this what’s right for my parent? Is this what’s right for me?”

Some health care organizations have already been doing this for years and years. Group Health has shared decision-making aids for 12 health conditions in 6 specialty areas: orthopedics, women’s health, urology, back care, breast cancer, and cardiac care.

There are online handouts and videos that are available to members. This is a recent case study and on the right you can see the links to them. http://www.ghc.org/features/feature.jhtml?reposid=/common/features/story/20110103-treatment.jhtml

Thanks for bringing this ted talk to life…very much like his 3 simple C’s that patients- all of us- must take on to help lift the ‘fog of healthcare’:

curiosity, competence and courage…

Two facts stand in the way of believing “you” can change healthcare.

1.The vast majority of Advanced Healthcare Directives are ignored or overridden, even among this nation’s most prestigious medical centers.

2.Dartmouth’s own research has shown that the volume, intensity and variation in healthcare is largely the product of the local medical culture.

I would like to see a sequel that addresses these realities.

Hi Ron – may I ask your background so I can understand your perspective?

I’m sure you watched the whole video, in which Mulley cited exactly those points. (Right?) So I don’t understand what you’re saying.

Maybe it’s this:

On point 1 (advanced directives being ignored), yeah, we do have to change the culture. The only remedy I’ve seen be effective is for the consumer / family to be VERY aware of this and be VERY CLEAR with hospital staff IN ADVANCE, and perhaps even threaten mayhem if it’s not honored. (That’s not what Mulley says, but I guess it’s in line with us “revealing our preferences.”)

Your point 2 (Dartmouth’s research) is exactly the point of the whole talk. And again, if we don’t make our preferences clear – including that we WANT our preferences to be heard and honored – inertia will keep things going as they are going.

Si?

Wonderful! Thanks for sharing this important message. Let’s continue to spread the word.

This was a terrific talk, and I thank you for the great summary of highlights, Dave. I agree wholeheartedly with the premises and the key points.

One point he made, though I don’t think he quite connected all of the elements, was that regional variation is a huge issue, related to the geography-based and personal biases of the doctors patients happen to see. The Dartmouth Atlas is a testament to that, and Atul Gawande’s seminal piece in the New Yorker highlights this beautifully. But a key element of avoidable ignorance is the ability to overcome geography and the personal biases of any one doctor or team of doctors that a person happens to see by making good information available online. We need to be exposed to ideas outside of our experience that was previously limited by geography but no longer needs to be. At their best, online patient communities are a terrific resource for overcoming these limits.

So I think that the internet can serve as the disruptive technology to break the location-based challenges raised by Ron Hammerle above. With regard to his first point, I believe, as a doctor working in the arena of oncology (with its attendant significant component of terminal care) for more than a decade, that the crossed signals about end of life care are often based on high emotions of many other people involved, such as if a family member or a neighbor calls 911 for a patient dying at home: if EMTs come and don’t see a DNR/DNI document front and center, they are beholden to default to maximal aggressive care. Or if a spouse demands maximal care despite a request by the patient for no extraordinary measure, I can imagine a medical team deferring towards more aggressive care in the absence of real consensus. But I have almost never seen or heard of a doctor knowingly overriding a patient request to not receive extraordinary measures, and in the cases where they have not pursued maximal aggressive interventions, it has always been in a setting where this has been considered “futile treatment” by all of the doctors involved, and for which intubation and CPR aren’t generally felt to be mandated or appropriate. Even when these measures are felt to be inappropriate, I’ve almost always seen medical teams honor patients wishes for extremely aggressive care despite their judgment.

I think one thing I would do is step back and clarify whether it’s really true that the vast majority of actual written and publicly known advance directives are actually ignored or overridden. I would like to see the quality of that evidence.

Jack, I myself don’t have the citation about end of life care – here’s hoping someone will step up.

Anecdotally (which is not what you asked for), here’s a item from this blog, Oct. 2008, by Paul Grundy MD, about what happened to his father. If this can happen to the head of worldwide healthcare for IBM, even after clearly stipulating their wishes, something’s VERY wrong – especially if the physicians involved escape prosecution for assault and battery.

Not to mention those physicians’ involvement in bilking the Medicare system for unwanted care.

Jack’s comments and personal clinical experience relating to conflicting requests in the care of terminally ill patients certainly rings true for many individual physicians, nurses and hospitals.

When measured within the context of large groups of caregivers in the USA, however, Robert Wood Johnson studies over the past two decades have shown that the vast majority of advanced healthcare directives are not followed.

The seminal research and findings in this area are known as the “SUPPORT” studies, “Phase 1” and “Phase 2” (“Study to Understand Prognoses And Preferences For Outcomes and Risks of Treatment”). The Phase I study results were first published in JAMA, Nov 22/29, 1995, pp. 1591 ff.

The RWJ Foundation has subsequently funded a series of follow up research, including funding to Dartmouth, to try to discover ways of improving physician and hospital “compliance”–a provocative word that is most often applied to patients.

For Dave and others interested in following this ongoing issue, Google any of the above key words.

The key point in my initial comment is that changing social behavior is much more challenging that one might be led to believe.

Patients as a group are under-represented where health care decisions are being made—in government, in marketing, in hospital systems.

The patient, singular, can determine most, if not all, aspects of care. It requires personal research, good questions and timely personal data. The digital PHR will become an essential tool, one that is more than an electronic filing cabinet. The PHR is an interactive software platform that files, organizes, FAXs, and communicates. It provides for eVisits, appointments and makes sense of eRx for the patient. Those with chronic illness or those taking care of a distant parent already know this. When physician and hospital EHRs are enabled for bidirectional transmission (happening slowly) no patient will have optimal care without one. For those who have health problems now, the PHR is an invaluable resource.

Cant we just solve our health? http://freshmanefforts.com/?p=5

Seriously, what do you think?

Yes, Dan, eating better is often noted as a way to stay healthier and avoid the costs and other problems of medical care…

As we prepare for the Patients in Power Conference in Athens, Greece, (www.patientsinpower.gr), I revisited this great post and listening once more to Al Mulley…

Yes, the question in Europe is indeed Who can fix the ailing healthcare systems…