A fundamental precept of participatory medicine is that health care should not be a spectator sport—it’s best practiced in a participatory manner. This requires engagement from both the patient and the clinician.

Yet the typical behavior of health encounters is not that. Too often, physicians still refuse to openly communicate, share information with patients, and partner with them in decision-making, and patients still assume a passive role, thinking that in some way they can get healthy without being engaged. This disengagement from both sides is what I call the “car wash” model of health care, in which the disengaged patients passes through the health care system and gets “health” sprayed on them by health care professionals. This model is not efficient, effective, or satisfying. But many, myself included, thought that that’s how many people think about their health care.

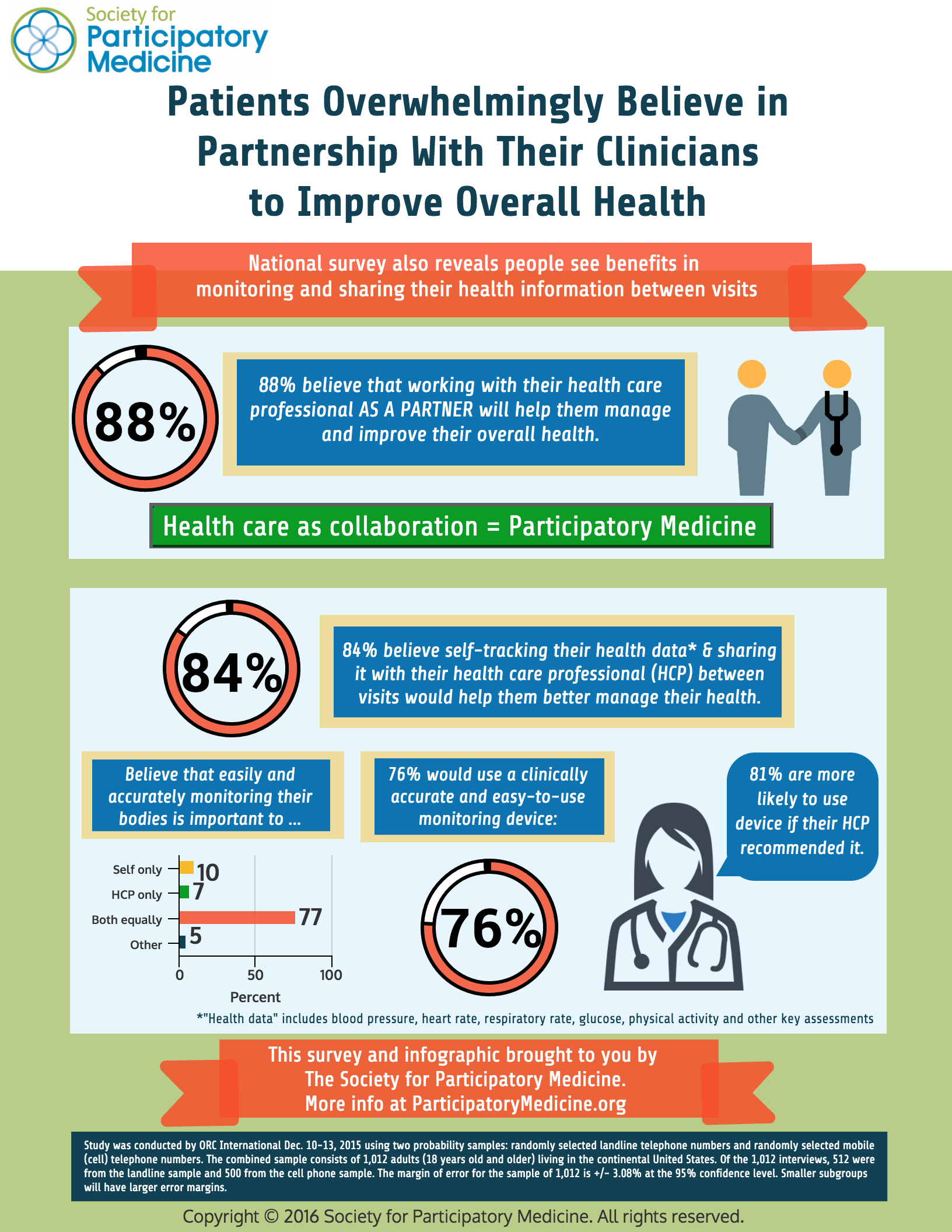

So it was quite gratifying to see the results of a new Society for Participatory Medicine survey. The survey, fielded by ORC International, a professional survey firm, asked 1000 adults five questions. We’re publishing the results in this downloadable PDF infographic: (Click to download)

A key finding: 88% of people believe that working with their health care professional as a partner will help them manage and improve their overall health. This is a stunning endorsement of the participatory health care model, which suggests that partnership, or collaboration, between the patient and their physician (or other clinician) is an ideal model of health care. (I’ve written and spoken about this in the past.)

Part of collaboration is sharing of information. We’ve known for five years, from the OpenNotes study, that patients want access to their health records, and sharing from health care professionals to patients is critical. But information must flow in both directions in a collaboration. And that means that patients should ideally be acquiring and sharing their health information with their health care professionals—and not just during visits. This idea is sometimes called patient-reported outcomes or in a more general sense, patient-generated health data.

Prior research has shown that self-monitoring can result in better care than in-office monitoring in areas like hypertension and diabetes, and various types of self-monitoring is frequently used in these conditions as well as congestive heart failure, asthma, some cardiac rhythm disturbances, and other conditions. The McKinsey 2015 Consumer Health Insights survey found that a minority of respondents had used a technology of some type to monitor their health status, with up to 40% of young adults having done so. And although there is great potential, not all studies have demonstrated improvements of clinical outcomes with mHealth tools. And, at least as far as fitness trackers are concerned, most adults don’t use one and more than half that have tried have abandoned them within two years. However the market for wearable monitors is expected to rise from $20B to $70B by 2025 and the patient monitoring device market will reach almost $25M by 2020.

But until now little has been known about the interest or willingness of the general population to self-monitor using a device—for things like blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, glucose, and physical activity—and to share this data with their health care professionals. In this survey, 84% of respondents felt that monitoring themselves with a clinically accurate device between visits was important to their health. Moreover, when asked whether it was important to themselves only, their physicians only, or both, 77% felt that it was equally important to themselves and their health care professional. In fact this information sharing is important: a recent study in which patients self-monitored but did not collaborate with their physicians showed no impact on clinical outcomes or costs of care. On the other hand, a recent survey by Pew Research Center revealed that people are generally willing to share their health information with their physicians in exchange to streamlined access to their medical records and online convenience transactions, but some expressed concerns about privacy and security of their stored health data.

But feeling that something is important and being willing to do it are two different things. 76% of the respondents told us they would use it and most of those said they would share the information with their health care professional, further underscoring that patients view health care as a partnership. Furthermore 81% told us they would be more likely to monitor themselves with a device if it was recommended by their health care professional, making abundantly clear that the clinician is absolutely still the trusted authority: patients view e-health devices as a new tool for health, not a substitute for clinical care.

This survey will spark many additional research questions. For example, are attitudes dependent upon socio-economic status? Health status? Age? Will people who say that they will self-monitor actually do so? What types of systems for sharing self-monitoring data with health care professionals will be most acceptable to patients? To physicians?

But the results are exciting because they shows us that Americans want to partner with their health care professionals and they are willing to participate in monitoring and sharing their physiologic information with their health care professionals—especially if they are asked to do it.

Quality of infographic very poor – can’t read. Unable to download the infographic. Could I get the full report?

Here is the direct link to the infographic: http://pmedicine.org/epatients/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/01/SPM-Infographic-on-Partnerships-and-Self-Monitoring-1-2016.pdf.

More information available at http://participatorymedicine.org.

Hope this helps.

Let’s stop blaming patients and physicians for the apparent lack of engagement going on in exam rooms across the US and elsewhere.

If we need to ascribe blame let put it where it belongs … on the archaic role definitions and behaviors taught to physicians in medical school (Doctors are the experts)… and the corresponding role orientation and behaviors passed on by physicians to their patients beginning in childhood (patients are supposed to be passive and do what they are told).

Patients are passive in the exam room because they have been socialized to assume a passive, compliant role once the exam room door closes. The evidence supporting my argument is quite large.

Patient talk time during the typical office visit is miniscule compared to physicians. Patients are reluctant to verbalize concerns of any kind directly to physicians instead relying upon verbal and non-verbal “cues” to signal to the physician a need to talk.

The average patient presents an average of 6 “attempts” per visit to engage the typical physician in conversation. To busy physicians these “cues” are hard to recognize and easily missed or ignored. On average physicians miss or ignore up to 70% of patients attempts to engage them in conversations about their health.

Why? It is not because physicians don’t care or lack the time. It’s because most physicians still employ the same disease-focused style and “I know best” role orientation that they learned 100 years ago in medical school. You know, where physicians focus on the disease a person has … not the person with the disease.

Most physicians will tell you in private that they stop listening to the patient after they have arrived at a DX and TX plan. Patients sense this … and have figured out when to speak up and when to remain quite. Many patients are actually afraid to challenge their doctors for fear of being labelled “difficult.” I have experienced this very thing first hand with my wife’s care.

My point? Let’s accept as a given that people want to be engaged. Let’s reframe the discussion around addressing the real barriers to meaningful patient engagement … those being redefining the physician’s and patient’s role in care delivery and the new behaviors they must learn in order to assume these new roles.

More on this subject can be found on mindthegapacademy.com.

I fully agree with you, Steve, and I do read your blog. I’d like to enlist your support in changing the culture of health care. Please join the Society and lend your wisdom, expertise, work, and also help us to raise funds to achive our goals. I’d love to get your involvements. And bring others with you! The culture of health care won’t change without concerted effort.

Thanks for your thoughtful comments.

Problem is whether doctors will collaborate with us. I’ve found a bunch that say my way or the highway, I’m in demand, dump the patient.

Yes, Vic, this is a terrible problem. I’m always sad to hear about these examples. I’ve also tried to work with patients who won’t engage. That’s why the Society is working to change the culture of health care–which requires influencing all stakeholders.

We need help in this effort! Please join the Society and lend your support (work effort, ideas, fund-raising, etc.). And if you work for a company, get them to join, as well.

We have work to do–let’s get started.

The data here is important. I’ve written about this topic, The physician as a brand should look at that visit not as a one time event in a string of events. It is a way to build a brand platform based on patient needs and goals.

The Office Visit is Not a Drive By

http://www.bioc.net/blog/2012/5/9/the-office-visit-is-not-a-drive-by.html?rq=drive%20by

Shared Decision Making is key to improving this dynamic. In my estimation a goal beyond the clinical exam of an office visit is to have both the HCP and the patient establish a foundation for better outcomes by managing knowledge and sharing problem solving.

Changing the Office Visit From Transaction to Value Experience

http://www.bioc.net/blog/2012/5/23/changing-the-office-visit-from-transaction-to-value-experien.html?rq=drive%20by

Well done study thank you

Thanks for your comment, Mark. Your blog post are spot-on and I recommend them to readers. In fact, very similar to my approach to patients. I would suggest that what you’re describing is actually participatory medicine–which is the theme of the Society for Participatory Medicine and I would encourage you to join if you aren’t a member and become a leader. It would be great to share your perspectives.

The idea of moving people along a continuum of behavior change was described by James Prochaska in 1977, and that is exactly the model I apply to move my patients along a continuum of engagement. Also, your described periodic assessment of patient engagement might be the Patient Activation Measure.

One problem that remains is health care professional unwillingness to see the importance of this bilateral engagement, particularly when they’re stuck in the fee-for-service payment model. But that is something the Society is trying to change.

This is great, we need more surveys like this.

Will you be publishing the results in detail, and is there more information on the age and health status of respondents?

As I focus on older adults — who are especially likely to be interacting with the healthcare system — I’m very interested in learning more about their views on these topics.

Hi Leslie. Unfortunately this was a simple 5-question survey meant as a first step. We have some information about the respondents for classification purposes, and the cross-tab data can be downloaded here. We did not collect information about health status, simply because of the limitations of budget and time, but I agree there are a number of factors that might influence individual responses to these questions. This is a start and not definitive research.

Thanks for the comment.

Hey Danny, Good to see your article and I appreciate the way you describe the whole scenario. I want you to ask something. Tell me, the behaviour of physicians in the context of refusing open communication with their patients is acceptable or not?