“To help inform patients of the best scientific knowledge…”

“…as future physicians, they realize that part of their contract with society is to meet patients where they are and to help inform patients of the best of scientific knowledge about the conditions that patients or their loved ones are reading about on Wikipedia.”

— from the interview below

This Thursday in Montreal, Medicine Day at the big WikiMania conference will include an important update on a radical, wonderful, disruptive project that’s bearing fruit big-time: WikiProject Medicine,

Three years ago we reported here on an intriguing and culturally significant development: fourth year medical students being coached on how to upgrade Wikipedia articles on medical subjects. If this subject interests you I encourage you to read that full post, and others linked here, especially the meaty comments on some posts.

In the three years since, important progress has been made – it’s now clear that this model is really working. This month the two principals of that post sat down again for another video interview: Peter Frishauf and Amin Azzam MD of UCSF (University of California at San Francisco). Here is a link to a transcript (4000 words), heavily annotated with links by Frishauf, below is our discussion of how important we think this is and why, and here’s the video of the interview:

WikiProject Medicine update interview, July 2017

Highlights of the medical student training program

-

Dr. Azzam teaching the class, 2015. Source: https://wikiedu.org/blog/2016/04/05/medical-students-wikipedia/

Students are taught about WIkipedia’s system of grading article quality.

- They’re also taught about the culture and methods of editing Wikipedia, including the back room “Talk” pages where things sometimes get argued out — in effect a form of peer review. In other words, they’re taught to become real “Wikipedians”

- They select Wikipedia articles that interest them, have lots of pageviews, and don’t have a great quality rating. In other words, the focus is on articles where improvement will make a difference to a lot of people.

(I discovered you can learn a ton more about it by browsing through a Google Image Search for Amin Azzam Wikipedia!)

Highlights of project results discussed in the video

-

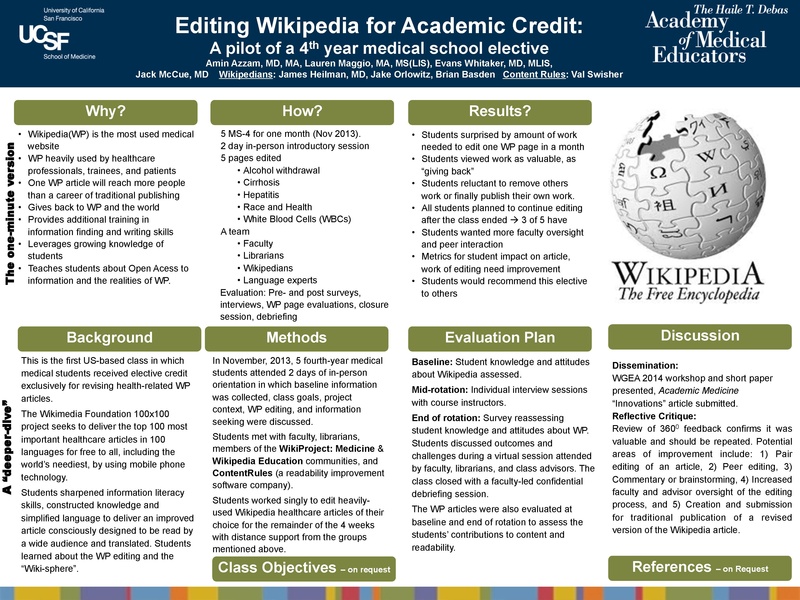

Source: Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Wiki_medicine_presentation_-_UCSF_medical_education_-_2014_Western_Group_on_Educational_Affairs_-_slides.pdf&page=5

80 students have participated so far in the UCSF course.

- The idea of a course like this has spread.

- 150 students have participated in a similar course at the UCSF school of pharmacy, editing pages on the most heavily prescribed drugs

- Similar projects have begun in Tel Aviv and in Fremantle, Western Australia

- Students learn to peer review each other, and then (as with all Wikipedia) the discussion is posted on the article’s Talk Page – which is in fact fully open peer review.

- Wikipedia edit-a-thons are happening in medical schools now – student-driven self-directed projects

- The Hewlett Foundation has awarded a grant to Dr. Azzam and Osmosis to spread the project to other medical schools, starting with five this year.

- The video content produced by Osmosis is a natural fit for this project.

- The project’s results have just been published in the top-tier journal Academic Medicine:

- The 80 students have edited 65 Wikipedia pages, adding 93,000 words and 605 references.

- Those pages had 1.8 million views during the 30 days of active editing.

- Then, through March 23 those 65 pages had 34 million page views.

- 360 pharmacy students edited 177 pages, which were viewed 2.3 million times during the editing.

- Article quality has been assessed by two physicians. (See tables in the article and in the video.)

- As noted in our 2014 post, it’s harder to upgrade your quality rating on Wikipedia than it is to get doctors to say you improved it. Yes, WIkipedia has tougher quality standards,

- “We … tend to defer to expertise without questioning the validity of statements that people who have initials after their name like me say.” [More on this below.]

- The Wiki Education Foundation is doing similar work in non-medical fields.

As you’ll see, there are certainly challenges. But what’s exciting is the clear signs that this approach of editing medical content to make it more reliable and understandable is working: it’s producing results, it’s bearing fruit, and it’s scaling.

Dimensions of the social, cultural, and intellectual changes embodied in WikiProject Medicine

It’s hard to know where to start in saying how profound it is that this is working. So many assumptions about authority and reliability are called into question, all of which is foundational to the culture shift this Society is helping bring about. How can we articulate what’s happening here, what specifically it’s changing, and what it means for the arriving future of participatory medicine?

Our 2014 post listed these earthshaking innovations compared to traditional peer review:

- A major advantage: transparency on who edited what, with public discussion

- Another big deal: the patient perspective is welcome.

- Crowd vs credentials: Medpedia and Britannica

For this year’s update, here are some additions – some key questions we can now say are being disrupted successfully:

1. Of course in medicine accuracy is important. What’s the best path to reliable information?

Just 12 years ago (2005) the world was sure that the best source was experts with strong credentials. Then, as reported at “Crowd vs Credentials” in our previous post, Nature compared articles from Britannica (the “credentials” method) and Wikipedia (a self-governing “crowd” without a single source of authority) and found the two sources’ accuracy comparable. What the heck??? There’s garbage on the internet – how could an ungoverned mob of unwashed nerds even come close to Britannica?

The answer to “how” is that when crowd is done right, it corrects the garbage, faster than a printed publication can. That’s a radical change in our mental model of how to home in on best advice.

By the way, five years after the Nature article, Britannica produced its last print edition.

In the same post we reported that a Silicon Valley startup called Medpedia had tried to solve the quality issue for medical information by hiring experts. At their founding in 2008 I’d noted this, from their “who can contribute” FAQ:

If you are an MD or PhD in the biomedical field, you can apply to become an Editor and make changes directly to Medpedia articles (See more below). If you are anyone else, you can use the “Make a suggestion” link …

There can be no clearer explicit declaration that people with credentials must know what they’re talking about, and the best anyone else is allowed to do is suggest things.

In early 2009 they went into public beta. We posted Medpedia: Who gets to say what info is reliable?, and SPM co-founder John Grohol of PsychCentral noted (scroll to his Feb 24 comment) “I can’t go into all the things wrong with the article on depression … “ and called one expert-approved statement “stupidly simplistic.”

So much for reliability – our 2013 post noted that MedPedia had failed and gone out of business.

2. Who gets to decide which facts to include, which facts are important?

Again, the conventional wisdom has been “learned authority.” But in Wikiproject Medicine, the users of the information get to edit it – “improve” it, in Wikipedia’s terms. And if others say the edit was wrong, they can undo it.

Sound chaotic? That’s why this news is so important: it works.

3. Who gets to say whether the writing is understandable and thus helpful?

Medicine loves to complain about the public’s “health literacy.” That’s like the computer tech support joke about telling a customer they’re too stupid to own a computer.

Note how the computer industry has since unfolded: users and buyers have migrated heavily toward usability, and vendors who had that attitude are generally out of business. (Remember when websites too often had forms and menus that were hard to understand? I personally sat in meetings where old-style experts complained that users were too stupid to appreciate how good our content was.)

Note too that a driving factor in that decades-long change was “TCO” – total cost of ownership: companies learned that it wasn’t just the purchase price that mattered, it was all the long-term consequences of that choice, and bad usability caused big long-term problems. So it is with healthcare: people tend not to adopt changes and information that they can’t understand.

That’s why for years I’ve refused to discuss health literacy without discussing the clarity of what we’re supposed to understand. See our 2011 post Health Literacy Missouri: Clarity is Power.

Do you see any other big shifts embodied in this project?

The times they are a-changin’.

At times like this it’s essential to put change into context. Without that, our thoughts about the future are likely to get whiplash as the far-out future suddenly whips past.

Consider this brief timeline:

- 1994:

- The first commercial browser, Mozilla, was born. Many consider this the birth of the Web.

- Our founder “Doc Tom” Ferguson was medical editor of the Whole Earth Catalog’s millennium edition

- ACOR, the network of cancer patient listservs that I joined in 2007, was founded by SPM co-founder Gilles Frydman

- 1995:

- Doc Tom published his extraordinary “triangle slides” showing how healthcare would be turned on its head by the radical shift in access to information.

- Peter Frishauf launches Medscape at SCP Communications, Inc. First trusted medical info site open to patients and MDs equally, a radical concept in its day (and a perfect companion to the inversion of power in Doc Tom’s slides).

- 1996: Doc Tom published Health Online: How To Find Health Information, Support Groups, And Self Help Communities In Cyberspace, with chapters ranging from how to get an email account to lists of online health communities (most of them pre-Web)

- 1998: Google was founded.

- 2000: Ferguson’s first BMJ article: “Online patient-helpers and physicians working together: a new partnership for high quality health care” includes this:

- “The whole structure of medicine has been based on the assumption that physicians have the current information and patients do not. The bottom line is, the consumer will have virtually all the information the professionals have. This is comparable to the way communism fell. Once people start getting in good communication you won’t be able to play the game in the same way.”

- 2001: Wikipedia was founded.

- 2002: Ferguson published the mind-challenging BMJ editorial “From patients to end users“, pointing to how when access to information changes, capabilities and thus roles will change.

- 2005: Nature published its comparison of Wikipedia and Britannica. (WIkipedia was only four years old.)

From the birth of the Web to the young Wikipedia community overthrowing Britannica took 11 years. Wikipedia is now 12 years older and has developed tougher rules for article quality (according to this interview) than medicine itself has. Also during those years:

- 2008: Medpedia is founded to address “unreliability” of medical information online, modeled on traditional academic peer review.

- 2009: Ferguson’s friends organize the Society for Participatory Medicine and its journal, JoPM

- Editorial board member Frishauf authors Reputation Systems: A New Vision for Publishing and Peer Review: “Peer review as we know it today is broken. ,,, My thinking about peer review changed in 2002, when I discovered Wikipedia….”

- 2010: Britannica publishes its last print edition.

- 2013:

- Medpedia folds

- In my first essay in the BMJ, my oncologist says he’s not sure I could have survived if it weren’t for the information I got from ACOR patients … information that doesn’t exist in any journal.

- 2014:

- This course starts at UCSF

- The BMJ announces its Patient Partnership, including a patient panel advising the BMJ’s editors. Several members of our society have been appointed to the panel.

The results produced by Dr. Azzam and his collaborators demand that we look forward and ask: what will the next decade bring?? A hint: the medical students in that year will have never known a world without Google and Wikipedia, never mind the archaic era when people thought a book was the best place to look for the latest information.

How should we prepare for this era? How would you design knowledge systems – and train students, and patients – for such a world?

Recent Comments